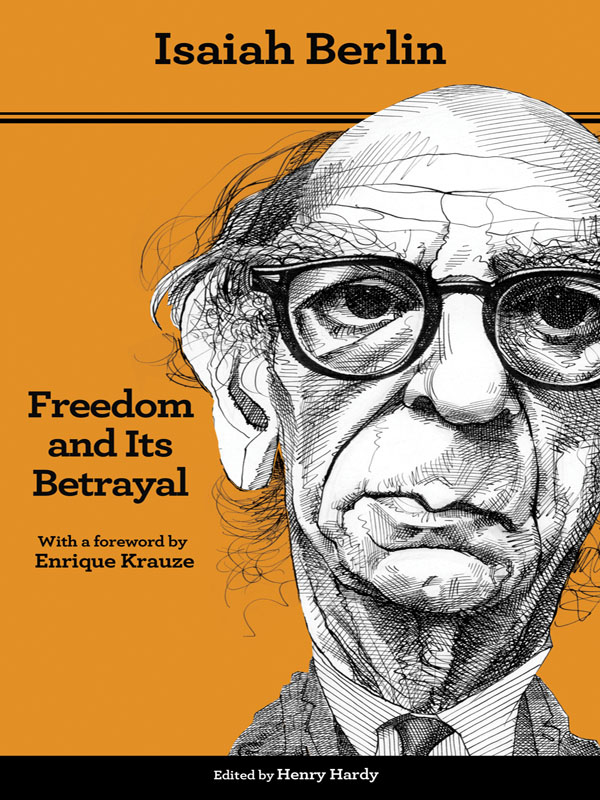

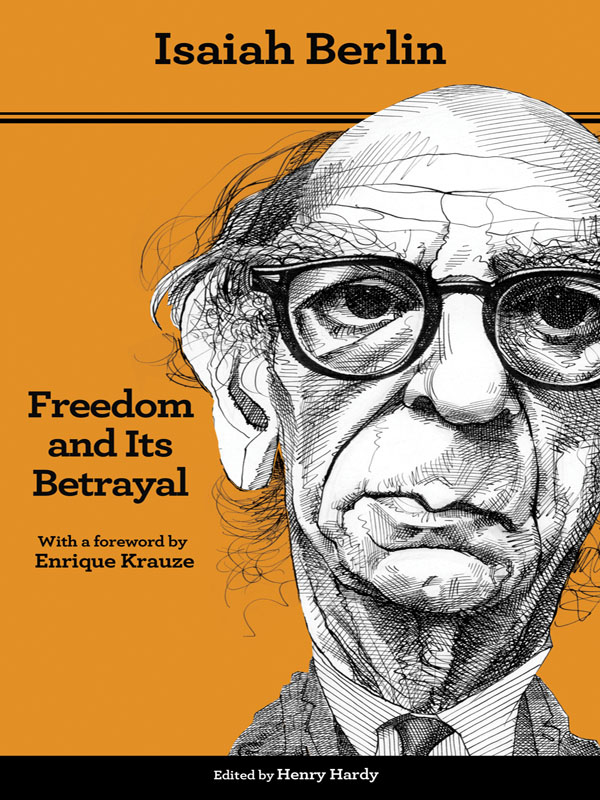

FREEDOM AND ITS BETRAYAL

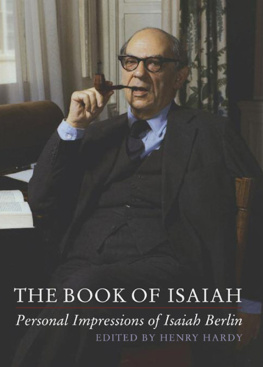

ISAIAH BERLIN WAS BORN IN RIGA, now capital of Latvia, in 1909. When he was six, his family moved to Russia; there in 1917, in Petrograd, he witnessed both Revolutions Social Democratic and Bolshevik. In 1921 he and his parents came to England, and he was educated at St Pauls School, London, and Corpus Christi College, Oxford.

At Oxford he was a Fellow of All Souls, a Fellow of New College, Professor of Social and Political Theory, and founding President of Wolfson College. He also held the Presidency of the British Academy. In addition to Freedom and Its Betrayal, his main published works are Karl Marx, Russian Thinkers, Concepts and Categories, Against the Current, Personal Impressions, The Crooked Timber of Humanity, The Sense of Reality, The Proper Study of Mankind, The Roots of Romanticism, The Power of Ideas, Three Critics of the Enlightenment, Liberty, The Soviet Mind and Political Ideas in the Romantic Age. As an exponent of the history of ideas he was awarded the Erasmus, Lippincott and Agnelli Prizes; he also received the Jerusalem Prize for his lifelong defence of civil liberties. He died in 1997.

Henry Hardy, a Fellow of Wolfson College, Oxford, is one of Isaiah Berlins Literary Trustees. He has edited (or co-edited) many other books by Berlin, including the first three of four volumes of his letters, and is currently working on the remaining volume.

Enrique Krauze is editor of Letras Libres. His latest book is Redeemers: Ideas and Power in Latin America (2011).

For further information about Isaiah Berlin visit

http://berlin.wolf.ox.ac.uk/

ALSO BY ISAIAH BERLIN

*

Karl Marx

The Hedgehog and the Fox

The Age of Enlightenment

Russian Thinkers

Concepts and Categories

Against the Current

Personal Impressions

The Crooked Timber of Humanity

The Sense of Reality

The Proper Study of Mankind

The Roots of Romanticism

The Power of Ideas

Three Critics of the Enlightenment

Liberty

The Soviet Mind

Political Ideas in the Romantic Age

with Beata Polanowska-Sygulska

Unfinished Dialogue

*

Flourishing: Letters 19281946

Enlightening: Letters 19461960

Building: Letters 19601975

FREEDOM AND ITS BETRAYAL

SIX ENEMIES OF HUMAN LIBERTY

ISAIAH BERLIN

Edited by Henry Hardy

Second Edition

Foreword by Enrique Krauze

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Published in the United States of America, its Colonies and Dependencies, the Philippine Islands, and Canada by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

press.princeton.edu

First published by Chatto & Windus and

Princeton University Press 2002

Second edition published by Princeton University Press 2014

The Isaiah Berlin Literary Trust and Henry Hardy 2002, 2014

Editorial matter Henry Hardy 2002, 2014

Foreword Princeton University Press 2014

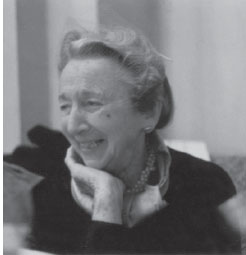

Photograph of Anna Kallin courtesy of Tatiana Wolff

Flicien David in Saint-Simonian Attire by Raymond Bonheur:

Collection Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Muse Municipal

The moral right of Isaiah Berlin and Henry Hardy to be identified as the author and editor respectively of this work has been asserted

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-15757-3

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Garamond Premier Pro

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

To the memory of Anna Kallin 18961984

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Isaiah the Prophet

Enrique Krauze

FREEDOM AND ITS BETRAYAL: Six Enemies of Human Liberty is a collection of six remarkable lectures (as edited by Henry Hardy) that Isaiah Berlin delivered on BBC Radio in the autumn of 1952. They are an impassioned political interpretation of what Berlin sees as the authoritarian legacy of six philosophers: Helvtius, Rousseau, Fichte, Hegel, Saint-Simon and Maistre. In response T. S. Eliot offered a left-handed compliment to Berlins torrential eloquence Hundreds of thousands listened to the series and Berlin received many enthusiastic letters.

Berlin had first treated this material earlier in the same year, when he delivered the Mary Flexner Lectures (at Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania) under the title Political Ideas in the Romantic Age. Lelia Brodersen, who was briefly his secretary during his residence at Bryn Mawr, was present at the lectures. She would remember the furious stream of words, in beautifully finished sentences from the professor who in a true state of inspiration drew his distinctions between various forms of freedom.

He had prepared himself with great energy for these lectures. According to his biographer Michael Ignatieff, in 19501 Berlin read furiously the works of the eighteenth-century French philosophers (Diderot, Helvtius, Holbach, Voltaire) and the German Romantics (Schelling, Herder, Fichte). But perhaps the fury to which Ignatieff alludes had less to do with Berlins academic commitment than with the sense that he was beginning to find his personal vocation and his own voice for a confrontation with history.

The highly positive reception of these lectures must have further strengthened his convictions. Their title reflects the moral fibre of Berlins thought, which resembles that of the Russian thinkers who would later become his subject. Even today, read not heard, But how did Isaiah Berlin arrive at this point and these specific insights?

The post-war world imposed the need for political and moral definitions. Nazism had been destroyed, but Soviet totalitarianism remained, supported by the initial prestige of the Russian Revolution and by the progress, real or imaginary, of the Russian economy. It was all legitimised by the philosophy of Marxism, which presented a defiant challenge to its critics. Karl Popper had earlier responded to this challenge with his compendious and George Orwell published Animal Farm and 1984, after writing (before and during the Second World War) various criticisms of the Soviet State and its Western sympathisers. At the other end of the scale, some of Berlins colleagues (including E. H. Carr and Christopher Hill) had reaffirmed their commitment to the Soviet Union and written their own histories of the Bolshevik Revolution. In 1945 Berlin had made a highly eventful trip to Moscow and Leningrad, during which he heard revelations from Boris Pasternak and Anna Akhmatova about the innermost workings of Stalinist repression. His experiences had helped to revive his interest in nineteenth-century Russian thought and literature and, at the same time, to establish one of the principal themes of his work, a criticism of the Soviet state based on the study of its intellectual precursors. But defining a position in the face of post-war realities was not the only dilemma Isaiah Berlin had to confront.

From 1940 to 1946, his diplomatic and intellectual contribution on behalf of the British Diplomatic Service, much of it in Washington, had earned him significant recognition in the higher spheres of American and British politics, but at the end of the war he was compelled to return to a cloistered academic life at New College in Oxford, a prospect for which he had little enthusiasm. And Berlin also had other concerns. Despite the solidity of his academic career and position, he felt himself to be a marginal person: a professional philosopher but with an inclination towards the history of ideas and towards literature; an exile from his native Russian culture set down at the intellectual heart of England; and, above all, a Jewish thinker divided (at times truly torn) between the will to integrate himself fully into English culture, history and society, and the call of his ancestors their history, their culture, their identity.

Next page