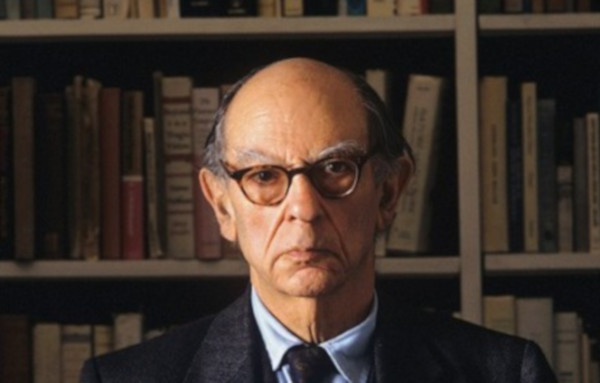

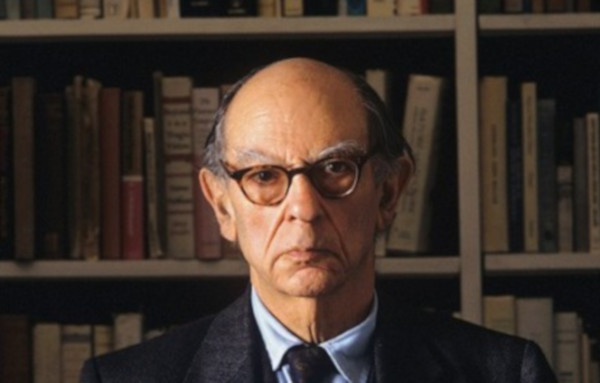

ISAIAH BERLIN WAS BORN IN RIGA, now capital of Latvia, in 1909. When he was six, his family moved to Russia; there in 1917, in Petrograd, he witnessed both Revolutions Social Democratic and Bolshevik. In 1921 he and his parents came to England, and he was educated at St Pauls School, London, and Corpus Christi College, Oxford. At Oxford he was a Fellow of All Souls, a Fellow of New College, Professor of Social and Political Theory, and founding President of Wolfson College. He also held the Presidency of the British Academy. In addition to Three Critics of the Enlightenment, his main published works are Karl Marx, Russian Thinkers, Concepts and Categories, Against the Current, Personal Impressions, The Crooked Timber of Humanity, The Sense of Reality, The Proper Study of Mankind, The Roots of Romanticism, The Power of Ideas, Freedom and Its Betrayal, Liberty, The Soviet Mind and Political Ideas in the Romantic Age. As an exponent of the history of ideas he was awarded the Erasmus, Lippincott and Agnelli Prizes; he also received the Jerusalem Prize for his lifelong defence of civil liberties. He died in 1997.

Original title: Three Critics of the Enlightenment

Isaiah Berlin, 2018

Digital editor: Titivillus

ePub base r2.1

Notas

[1] Two Concepts of Liberty, in Liberty, ed. Henry Hardy (Oxford and New York, 2002), 194.

[2] Two Concepts of Liberty, in Liberty, ed. Henry Hardy (Oxford and New York, 2002), 194.

[3] Two Concepts of Liberty, in Liberty, ed. Henry Hardy (Oxford and New York, 2002), 194.

[4] Two Concepts of Liberty, in Liberty, ed. Henry Hardy (Oxford and New York, 2002), 201.

[5] Two Concepts of Liberty, in Liberty, ed. Henry Hardy (Oxford and New York, 2002), 212.

[6]Esquisse dun tableau historique des progrs de lesprit humain (Paris, 1795), 366; Outlines of an Historical View of the Progress of the Human Mind

[7] Two Concepts of Liberty, in Liberty, ed. Henry Hardy (Oxford and New York, 2002), 208.

Notas

[1] The contract, dated 31 December 1959, specifies only essays on Vico and Maistre.

[2] The latter study was eventually included in Concepts and Categories: Philosophical Essays, ed. Henry Hardy (London, 1978; New York, 1979; 2nd ed., Princeton, 2013).

[3] Later included in Against the Current: Essays in the History of Ideas, ed. Henry Hardy (London, 1979; New York, 1980; 2nd ed., Princeton, 2013).

[4]The Crooked Timber of Humanity: Chapters in the History of Ideas (London, 1990; New York, 1991; 2nd ed., Princeton, 2013) and The Magus of the North: J. G. Hamann and the Origins of Modern Irrationalism (London, 1993; New York, 1994), both edited by Henry Hardy.

[5] Berlin was himself only too aware of the extent to which he tested the endurance of his publishers by the long delays, the unrealistic predictions and the changes of plan that characterised his experience of authorship: as he wrote to Hugo Brunner at the Hogarth Press on 24 July 1975, anyone dealing with me must be armed with considerable reserves of patience. That was no exaggeration, but the eventual outcome always more than compensated for the preceding frustrations.

[6]The Proper Study of Mankind: An Anthology of Essays, ed. Henry Hardy and Roger Hausheer (London, 1997; New York, 1998; 2nd ed., London, 2013).

[7]Der Magus in Norden (Berlin, 1995). The first draft of this foreword was composed by me at Berlins request, but he then characteristically rewrote most of it, I am glad to say.

[8] For completeness I should perhaps mention that a revised edition of vol. iv (1928), the Scienza nuova of 1744, appeared in 1942 rather misleadingly called a third edition, because the 1928 edition was itself a revision of an earlier edition by Nicolini. But this does not affect the citation system explained here, since this work is referred to by paragraph, and the paragraph numbering was not altered.

[9] The same applies to Vico, whose translators do not reproduce his ubiquitous emphases.

Notas

[1] B i 202.2.

[2] B ii 330.30.

[3] B ii 315.35.

[4] Goethe saw Hamann as a great awakener, the first champion of the unity of man the union of all his faculties, mental, emotional, physical, in his greatest creations man misunderstood and misrepresented, and indeed done harm, by the dissection of his activity by lifeless French criticism. In book 12 of Dichtung und Wahrheit he expresses Hamanns central principle thus: Everything that a man sets out to achieve, whether it is produced by deed or word or by some other means, must spring from all his powers combined; everything segregated is deplorable. Goethe wrote to Frau von Stein about his delight in grasping more of Hamanns meaning than most men. Goethes Liebesbriefe an Frau von Stein 1776 bis 1789, ed. Heinrich Dntzer (Leipzig, 1886), 515 (letter of 17 September 1784).

[5]F. W. J. Schellings Denkmal der Schrift von den gttlichen Dingen etc. des Herrn Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi [] (Tbingen, 1812), 192.

[6]Lebensnachrichten ber Barthold Georg Niebuhr aus Briefen desselben und aus Erinnerungen einiger seiner nchsten Freunde (Hamburg, 1838) ii 482.

[7] Jean Paul, Vorschule der sthetik, part 1, 14: ed. Norbert Miller (Munich, 1963), 64.

[8]Friedrich Heinrich Jacobis auserlesener Briefwechsel, ed. Friedrich Roth (Leipzig, 1825-7), i 438.

[9] B ii 230.9.

Notas

[1] Today part of the Russian Federation, and officially known since 1946 as Kaliningrad.

[2] See the interesting account in Anton Reiser (1785-90), the well-known novel by Goethes admirer Karl Philipp Moritz.

[3]Gedanken ber meinen Lebenslauf (W ii 9-54).

[4] W ii 21.3.

[5] W ii 21.25.

[6] In our day the capital of Latvia (then called Livonia, and part of the Russian Empire).

[7] The Wars of the Spanish and Austrian Successions, the rumblings which culminated in the Seven Years War, and the Anglo-French wars, as well as the colonial wars in India and elsewhere, seem to have made no impact on him.

[8] Edward Young, Night Thoughts (1742-5) ii 24, quoted at W ii 233.

[9] He retained this interest even after he changed his central opinions, as is shown by his appreciation of the writings of the Neapolitan abb Galiani. It should be added, though, that Galianis views were somewhat unorthodox: he argued against free trade and laissez-faire, laid stress on non-economic considerations of a social welfare State type, and was not uncritical of Montesquieu. See Ferdinando Galiani, Dialogues sur le commerce des bleds (London, 1770), and Philip Merlan, Parva Hamanniana: Hamann and Galiani, Journal of the History of Ideas 11 (1950), 486-9.

[10] Berenss remark is quoted by Herder in Briefe zu Befrderung der Humanitt: xvii 391.

[11] See Philip Merlan, Parva Hamanniana: J. G. Hamann as a Spokesman of the Middle Class, Journal of the History of Ideas 9 (1948), 380-4, and Jean Blum, La Vie et loeuvre de J.-G. Hamann, le Mage du Nord, 1730-1788 (Paris, 1912), 32-3.

[12] e.g. W ii 320.29, W iii 55-60.

[13] W ii 37.7.

[14] W ii 39.40.

[15] Rudolf Unger, in his excellent if somewhat ponderous Hamanns Sprachtheorie im Zusammenhange seines Denkens: Grundlegung zu einer Wrdigung der geistesgeschichtlichen Stellung des Magus in Norden (Munich, 1905) incorporated, in expanded form, into his Hamann und die Aufklrung (Jena, 1911) points to parallels in the instructions on the reading of the Scriptures by such pietists as Francke in 1693 and Joachim Lange in 1733. This is highly plausible, although Hamann never became an orthodox pietist and broke out in all kinds of from the orthodox point of view of the movement worrying and unaccountable directions. His relation to pietism is somewhat analogous to, say, Blakes relation to the Nonconformist and Swedenborgian currents in which he was brought up.