CHAPTER I

REALISM IN ART

A T the end of the long rue de lUniversit, close to the Champ-de-Mars, in acorner, so deserted and monastic that you might think yourself in the provinces, is the Depot des Marbres.

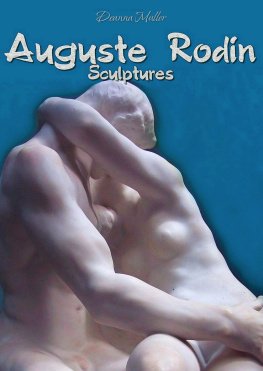

Here in a great grass-grown court sleep heavy grayish blocks, presenting in places fresh breaks of frosted whiteness. These are the marbles reserved by the State for the sculptors whom she honors with her orders.

Along one side of this courtyard is a row of a dozen ateliers which have been granted to different sculptors. A little artist city, marvellously tranquil, it seems the fraternity house of a new order. Rodin occupies two of these cells; in one he houses the plaster cast of his Gates of Hell, astonishing even in its unfinished state, and in the other he works.

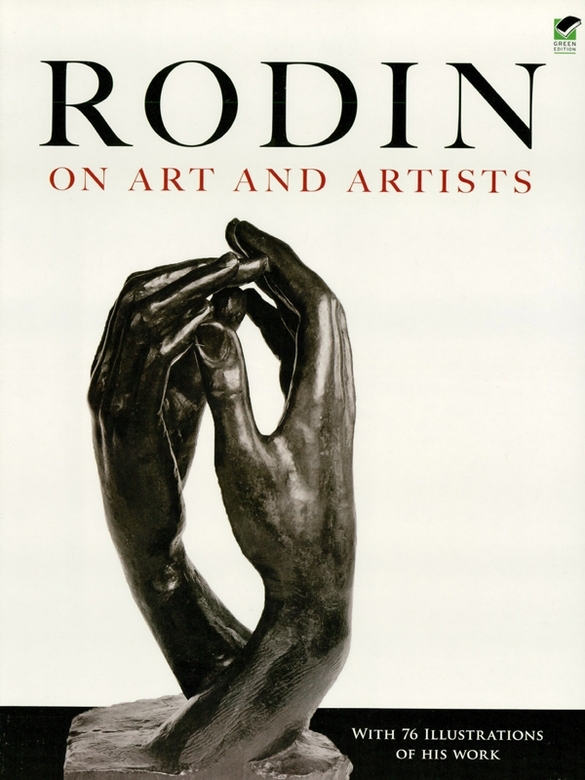

Ills. p. 23

More than once I have been to see him here towards evening, when his day of toil drew to its close, and taking a chair, I have waited for the moment when the night would oblige him to stop, and I have studied him at his work. The desire to profit by the last rays of daylight threw him into a fever.

I see him now, rapidly shaping his little figures from the clay. It is a game which he enjoys in the intervals of the more patient care which he gives to his big figures. These sketches flung off on the instant delight him, because they permit him to seize the fleeting beauty of a gesture whose fugitive truth would escape deeper and longer study.

His method of work is singular. In his atelier several nude models walk about or rest.

Rodin pays them to furnish him constantly with the sight of the nude moving with all the freedom of life. He observes them without ceasing, and it is thus that he has long since become familiar with the sight of muscles in movement. The nude, which for us moderns is an exceptional revelation and which even for the sculptors is generally only an apparition whose length is limited to a sitting, has become to Rodin a customary sight. The constant familiarity with the human body which the ancient Greeks acquired in watching the gamesthe wrestling, the throwing of the discus, the boxing, the gymnastics, and the foot racesand which permitted their artists to talk naturally on the subject of the nude, the creator of the Penseur has made sure of by the continual presence of unclothed human beings who come and go before his eyes. In this way he has learned to read the feelings as expressed in every part of the body. The face is generally considered as the only mirror of the soul; the mobility of the features of the face seems to us the only exterior expression of the spiritual life. In reality there is not a muscle of the body which does not express the inner variations of feeling. All speak of joy or of sorrow, of enthusiasm or of despair, of serenity or of madness. Outstretched arms, an unconstrained body, smile with as much sweetness as the eyes or the lips. But to be able to interpret every aspect of the flesh, one must have been drawn patiently to spell out and to read the pages of this beautiful book. The masters of the antique did this, aided by the customs of their civilization. Rodin does this in our own day by the force of his own will.

Ills. p. 12

He follows his models with his earnest gaze, he silently savors the beauty of the life which plays through them, he admires the suppleness of this young woman who bends to pick up a chisel, the delicate grace of this other who raises her arms to gather her golden hair above her head, the nervous vigor of a man who walks across the room; and when this one or that makes a movement that pleases him, he instantly asks that the pose be kept. Quick, he seizes the clay, and a little figure is under way; then with equal haste he passes to another, which he fashions in the same manner.

One evening when the night had begun to darken the atelier with heavy shadows, I had a talk with the master on his method.

What astonishes me in you, said I, is that you work quite differently from your confrres. I know many of them and have seen them at work. They make the model mount upon a pedestal called the throne, and they tell him to take such or such a pose. Generally they bend or stretch his arms and legs to suit them, they bow his head or straighten his body exactly as though he were a clay figure. Then they set to work. You, on the contrary, wait till your models take an interesting attitude, and then you reproduce it. So much so that it is you who seem to be at their orders rather than they at yours.

Rodin, who was engaged in wrapping his figurines in damp cloths, answered quietly:

I am not at their orders, but at those of Nature! My confrres doubtless have their reasons for working as you have said. But in thus doing violence to nature and treating human beings like puppets, they run the risk of producing lifeless and artificial work.

As for me, seeker after truth and student of life as I am, I shall take care not to follow their example. I take from life the movements I observe, but it is not I who impose them.

Even when a subject which I am working on compels me to ask a model for a certain fixed pose, I indicate it to him, but I carefully avoid touching him to place him in the position, for I will reproduce only what reality spontaneously offers me.

I obey Nature in everything, and I never pretend to command her. My only ambition is to be servilely faithful to her.

Nevertheless, I answered with some malice, it is not nature exactly as it is that you evoke in your work.

He stopped short, the damp cloth in his hands. Yes, exactly as it is! he replied, frowning.

You are obliged to alter

Not a jot!

But, after all, the proof that you do change it is this, that the cast would give not at all the same impression as your work.

He reflected an instant and said: That is so! Because the cast is less true than my sculpture!

It would be impossible for any model to keep an animated pose during all the time that it would take to make a cast from it. But I keep in my mind the ensemble of the pose and I insist that the model shall conform to my memory of it. More than that,the cast only reproduces the exterior; I reproduce, besides that, the spirit which is certainly also a part of nature.

I see all the truth, and not only that of the outside.

I accentuate the lines which best express the spiritual state that I interpret.

As he spoke he showed me on a pedestal nearby one of his most beautiful statues, a young man kneeling, raising suppliant arms to heaven. All his being is drawn out with anguish. His body is thrown backwards. The breast heaves, the throat is tense with despair, and the hands are thrown out towards some mysterious being to which they long to cling.

Look! he said to me; I have accented the swelling of the muscles which express distress. Here, here, thereI have exaggerated the straining of the tendons which indicate the outburst of prayer.

And, with a gesture, he underlined the most vigorous parts of his work.

I have you, Master! I cried ironically; you say yourself that you have accented, accentuated, exaggerated. You see, then, that you have changed nature.

He began to laugh at my obstinacy.

No, he replied. I have not changed it. Or, rather, if I have done it, it was without suspecting it at the time. The feeling which influenced my vision showed me Nature as I have copied her.

If I had wished to modify what I saw and to make it more beautiful, I should have produced nothing good.

An instant later he continued:

I grant you that the artist does not see Nature as she appears to the vulgar, because his emotion reveals to him the hidden truths beneath appearances.