Copyright 2016 by Rachel Corbett

All rights reserved

FIRST EDITION

Excerpts from letters by Paula Modersohn-Becker first published in German as Paula Modersohn

Becker in Briefen und Tagebchern 1979 S. Fischer Verlag GmbH, Frankfurt. English translation

1983 by Taplinger Publishing Company, Inc. Northwestern University Press edition published

1990 by arrangement with S. Fischer Verlag. All rights reserved.

Put out my eyes, and I can see you still and I read it in your word by Rainer Maria Rilke,

translated by Babette Deutch, from Poems from the Book of Hours, copyright 1941 by

New Directions Publishing Corp. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

Archaic Torso of Apollo, The Panther, and Self-Portrait from the Year 1906 from Translations

from the Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke, by Rainer Maria Rilke, translated by M. D. Herter Norton.

Copyright 1938 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., renewed 1966 by M. D. Herter Norton.

Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Excerpt from The Departure of the Prodigal Son from A Year with Rilke, translated and edited

by Joanna Macy and Anita Barrows. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Excerpts from Letters to a Young Poet by Rainer Maria Rilke, translated by M. D. Herter Norton.

Copyright 1934, 1954 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., renewed 1962, 1982 by

M. D. Herter Norton. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Excerpts from Letters of Rainer Maria Rilke: 19101926, translated by Jane Bannard Greene and

M. D. Herter Norton. Copyright 1947, 1948 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., renewed 1975 by

M. D. Herter Norton. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Barbara M. Bachman

Production manager: Louise Mattarelliano

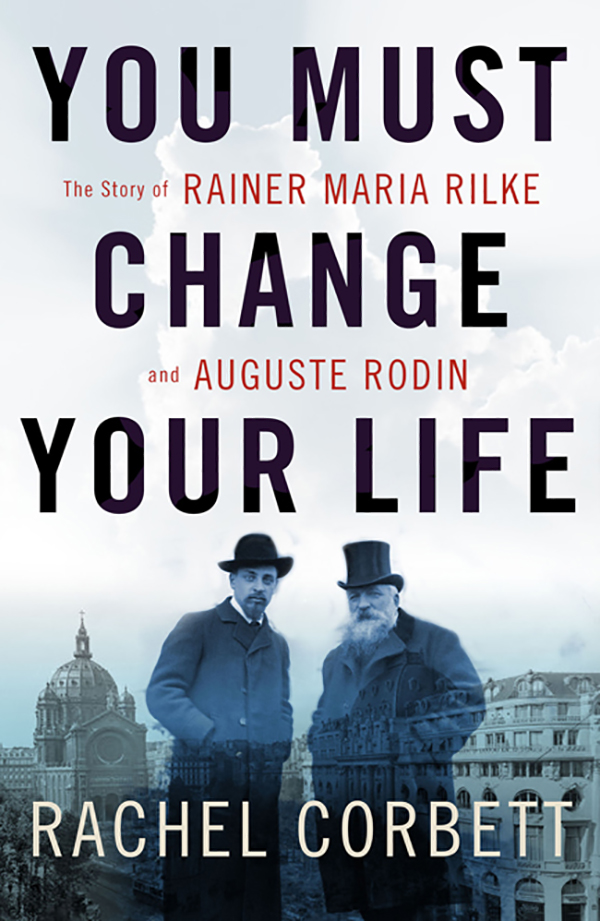

Jacket design by Keenan

Jacket photographs (Rainer Maria Rilke & Auguste Rodin) Albert Harlingue / Roger-Viollet / The Image Works; (Paris) Cap / Roger Viollet / Getty Images

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE PRINTED EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

Names: Corbett, Rachel, 1984- author.

Title: You must change your life : the story of Rainer Maria Rilke and

Auguste Rodin / Rachel Corbett.

Description: First edition. | New York : W. W. Norton & Company, 2016. |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016013563 | ISBN 9780393245059 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Rilke, Rainer Maria, 1875-1926Biography. | Rilke, Rainer

Maria, 1875-1926Friends and associates. | Authors, German20th

centuryBiography. | Rodin, Auguste, 1840-1917Biography. | Rodin,

Auguste, 1840-1917Friends and associates. | SculptorsFrance20th

centuryBiography.

Classification: LCC PT2635.I65 Z66144 2016 | DDC 831/.912 [B]dc23 LC record

available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016013563

ISBN 978-0-393-24506-6 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd. 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

I FIRST READ LETTERS TO A YOUNG POET WHEN I WAS TWENTY years old. My mother gave me the square, slender book with the title words Young Poet splayed grandly across the cover in gold script. The authors name, Rainer Maria Rilke, was strange and beautiful.

At the time, I was living in a Midwestern college town a few miles from where I grew up, in a mono-colored landscape of bland struggles and unspecial children. Like everyone else I knew, I had no interest in becoming a writer. As graduation loomed, the only drive I felt unmistakably was the will to leave. But I had no money and no clear destination. My mother said she had taken some comfort in the book when she was a younger woman, and thought perhaps I would appreciate it, too.

Reading it that evening was like having someone whisper to me, in elongated Germanic sentences, all the youthful affirmations I had been yearning to hear. Loneliness is just space expanding around you. Trust uncertainty. Sadness is life holding you in its hands and changing you. Make solitude your home. I saw how each negative in my mind could be reversed; having no prospects also meant having no expectations; no money meant no responsibilities.

Looking back, I see how Rilkes advice could be taken rather recklessly. But one can hardly blame him for that. He was only twenty-seven himself when he began writing this series of ten letters to an aspiring nineteen-year-old poet, Franz Xaver Kappus. He could not have fathomed then that they would be canonized as Letters to a Young Poet, one of the most frequently quoted texts at weddings, graduations and funerals alike, and what may today be considered the highest-brow self-help book of all time.

As the fledgling poet formed the words, the words formed him, allowing us to witness the making of an artist. What gives the book its enduring appeal is that it crystallizes the spirit of delirious transition in which it was written. You can pick it up during any of lifes upheavals, flip it open to a random page, and find a consolation that feels both universal and breathed into your ear alone.

While the genesis of Letters is by now well known, fewer readers know that the insight Rilke transmitted to Kappus was not exclusively his own. The poet began sending the letters shortly after he moved to Paris in 1902 to write a book about his hero, the sculptor Auguste Rodin. To Rilke, the raw, rough-hewn emotion of Rodins artthe hungry lust of the The Kiss, the alienation of The Thinker, the tragic suffering of The Burghers of Calaisgave form to the souls of young artists everywhere.

Rodin was at the pinnacle of his powers when he granted the unknown writer entre into his world, at first as his hovering disciple and then, after three years, his most trusted assistant. All the while, Rilke wrote down the masters every adage and bon mot and often paraphrased them for Kappus. In the end, Rodins voice emanates loudly from behind the pages of the letters, his wisdom reverberating from Rilke to Kappus and to the millions of pleading young minds whove read Letters in the century since.

OVER THE YEARS I had heard in passing that Rilke once worked for Rodin. The details rarely went beyond this snippet of trivia, but it always remained a curiosity in my mind. These two personas seemed so incongruous that I almost imagined them living in different centuries or continents altogether. Rodin was a rational Gallic in his sixties, while Rilke was a German romantic in his twenties. Rodin was physical, sensual; Rilke metaphysical, spiritual. Rodins work plunged into hell; Rilkes floated in the realm of angels. But I soon discovered how tightly their lives intertwined: how the artistic development of one mirrored the other and how their seemingly antithetical natures complemented each other; if Rodin was a mountain, Rilke was the mist encircling it.

As I struggled to grasp how these two figuresone in old age, one as a young manunderstood each other, my research brought me to empathy. What we understand today as the capacity to feel the emotions of others is a concept that originated in the philosophy of art, to explain why certain paintings or sculptures move people. Rilke studied the theory in college as the word was first being coined, and soon it appeared in seminal texts by Sigmund Freud, Wilhelm Worringer and other leading intellectuals of the time. The invention of empathy corresponds to many of the climactic shifts in the art, philosophy and psychology of

Next page