DRAWING THE HUMAN FIGURE

SUCCESSFULLY to build up the human figure in a drawing, painting or statue, either from imagination or from a model, the artist or sculptor must be possessed of a keen sense of construction.

The human body, with its varied beauty of construction, character and action, is so complex that it is essential for the student, artist and sculptor not only to have a clear knowledge of its intricate forms, but a comprehensive understanding and a habit of simple treatment in order to apply this knowledge to its artistic end.

The artist is immediately concerned with the external and the apparent. He views nature as color, tone, texture and light and shade, but back of his immediate concern, whether he be figure painter or illustrator, in order to render the human form with success, he stands in need of skill in the use of his knowledge of structure, of his understanding of action and of his insight into character. These things require a period of profound academic study.

When we consider the infinite variety of action of the human form, its suppleness, grace and strength of movement in the expression of the fleeting action, and farther consider that the surface of the body is enveloped in effects of light and shade, iridescent color and delicate tone, it is not to be wondered at that the students eye is readily blinded to the hidden construction of the form.

At this stage of the students advancement a careful study of artistic anatomy, as elucidated by Richter, Bridgman or Duval, familiarizing him with the bony structure of the skeleton, and the location, attachment and function of the muscles, will not only be helpful in furthering his own research, but will enable him the more readily to understand the theory of construction of the human body as presented in this book.

The theory of construction of the human figure here presented is based on the pictorial means usual in the expression of the solid, that is, the expression of the three dimensionslength, breadth and thicknessby means of planes. In the simple drawing the boundaries of these planes may be indicated by lines of varying weight, and in a tone drawing by the varying depth of the values. It is the discovery or search for the relative position, character and value of these planes that will engross our attention in the ensuing chapters.

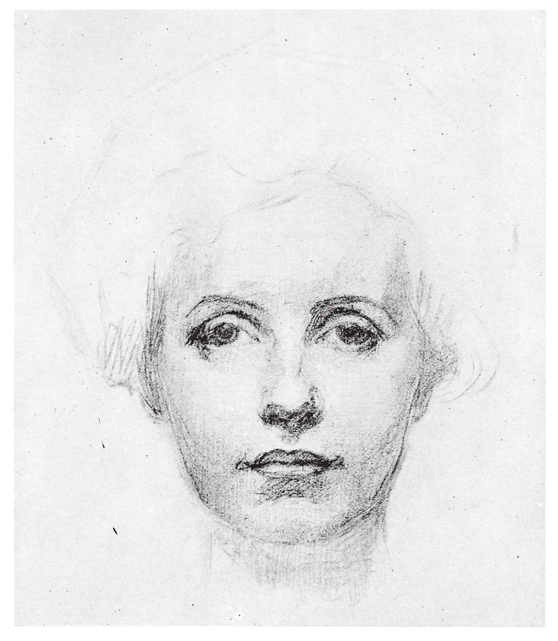

In the making of a thorough drawing of the human body, involving a sustained effort on the part of the student, whether in line, light and shade, or tone, the student goes through two stages of mental activity: first, the period of research, in which he analyzes the figure in all the large qualities of character, action and construction. In this analysis he acquires an intimacy with the vital facts, and this leads, as the work progresses, to a profound conviction. When thus impressed the student enters upon the second period, which deals with the representation of the effect dependent upon light and shade. Impressed with the facts in regard to the character of the model, understanding the action and construction, his appreciation enhanced by research, his lines become firm and assertive.

In the first period the students mind is engrossed with the search for the relative place the part shall occupy in conveying the impression of the whole; having secured the position of the part, the second period is occupied in turning the place for the part into its actual form.

The artists or illustrators final objective is the pictorial, and he uses any and all technical means and mediums to that end. He studies theories of color, perspective, effect of light and shade, values, tone, and composition; all may be studied separately and exhaustively so that he may learn the full import of eachso, too, the matter of form should be studied for its own sake. Every stroke of the artists brush should prove his understanding of the form of the subject-matter depicted; this includes insight into the character of the model, understanding of his action, and how the form is put together.

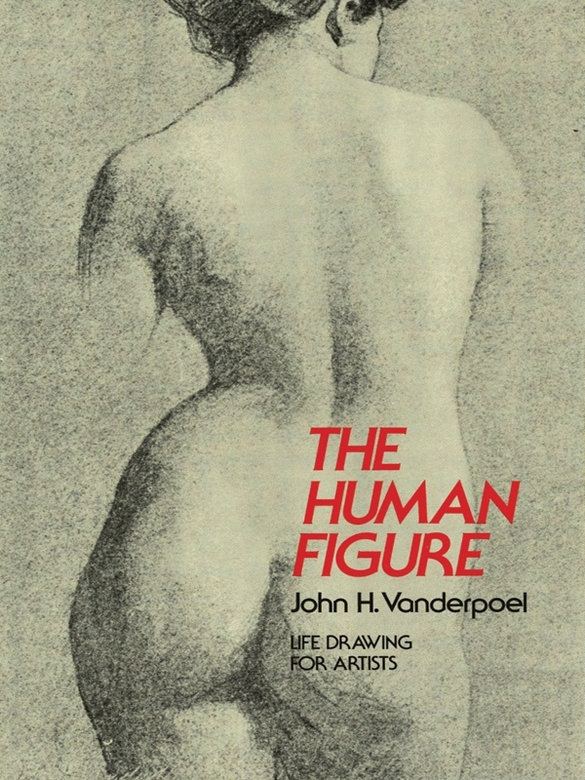

A figure posed in a full light, with its multitudinous variety of high lights, half-tones and shadowed accents, does not disclose its structural nature to the uninitiated student; it does not appeal to him as he stands dazed before it, for there is so little of shadow to go out from. Preferably he chooses a position where the effect of light and shade is strong, not because the construction is more evident, for the figure may have been posed only incidentally to that end, but because the strong effect appeals to him for his work with black charcoal upon white paper. In order that the student may the more readily understand the construction of the figure, as analyzed in the accompanying drawings, its parts and the whole have been so lighted as to show, through the effects produced, the separation of the planes that mark the breadth, front or back, of the form from its thickness. In this illumination the great masses or planes that mark the breadth relative to thickness of the human form are made plainly visible. Such illumination divides the planes that envelop the body into great masses of form which upon analysis disclose its structural formation.

The student must learn early to form a vivid mental picture of his model, and the first period of the development of his drawing is but a means to enhance this mental picture through profound research. This mental picture must include the figure in its entirety, so that no matter what minor form the eye may be attracted to or what line the hand may trace upon the paper, the nature of the relationship of the part to the whole may first be established.

An exhaustive line drawing made upon constructive principles, including understood action and strong characterization, will give added quality to the tone and light and shade of the students work. It might well be suggested in the development of the students skill as a draftsman that he vary the means according to the end required. Besides the outline drawing suggested above, he might venture into tone by smudging the paper with a value of charcoal and removing it for the masses of light with the fingers or kneaded rubber. Again a period may be spent in swinging in the action, proportions, and construction of the figure with long lines, and also in making quick ten or fifteen minute sketches. These efforts in connection with sustained work requiring a number of days for completion, which means the carrying forward of a drawing from the blocking-in stage to the complete effort, including tone, are commended to students.

Great skill in draftsmanship is highly desirable, but the student should be warned not to give it his sole attention for too long a period. He should test his skill and knowledge by memory drawing and by applying them to composition.