My Life with Charlie Brown

Edited and with an introduction by M. Thomas Inge

My Life with Charlie Brown

CHARLES M. SCHULZ

www.upress.state.ms.us

Designed by Todd Lape

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Copyright 2010 by Schulz Family Intellectual Property Trust. All rights reserved.

PEANUTS United Feature Syndicate, Inc.

PEANUTS is a registered trademark of United Feature Syndicate, Inc. All rights reserved.

All illustrations by Charles M. Schulz, PEANUTS United Feature Syndicate, Inc.

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2010

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Schulz, Charles M. (Charles Monroe), 19222000.

My life with Charlie Brown / Charles M. Schulz ; edited and with an introduction by M. Thomas Inge.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-60473-447-8 (alk. paper)

1. Schulz, Charles M. (Charles Monroe), 19222000.

2. CartoonistsUnited StatesBiography. 3. Schulz, Charles M. (Charles Monroe), 19222000. Peanuts.

I. Inge, M. Thomas. II. Title.

PN6727.S3Z46 2010

741.56973

[B 22] 2009033756

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

On behalf of Sparky this book is dedicated to his wife, Jeannie and his children Meredith Monte Craig Amy and Jill

Contents

Introduction

Charles Monroe Schulz, better known as Sparky among his family and friends, was twentieth-century Americas favorite and most highly respected cartoonist. His comic strip, Peanuts, appeared daily in over two thousand newspapers in the United States and abroad in a multiplicity of languages. Compilations of the strips sold in millions of copies during his lifetime and often topped best seller lists, and more recently a series of volumes collecting the complete run of Peanuts appeared in the New York Times listings.

Thousands of toy and gift items bore and continue to bear the likenesses of Charlie Brown, Lucy, Snoopy, and the other characters who populate their world. A stage musical based on PeanutsYoure a Good Man Charlie Brownhas remained one of the most frequently performed shows in American theatrical history, and several award-winning animated television specials continue to be shown annually and sold in DVD. Even today, almost a decade after the untimely death of Schulz on February 12, 2000, classic Peanuts reprints continue to hold their own space in major newspapers throughout the United States and in other countries.

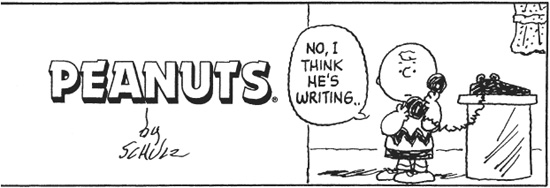

While sometimes bewildered by the enormous influence of the characters of his creation on American culture in general, Schulz held to a principle of integrity in the comic strip itself. Beginning with the first strip published on October 2, 1950, until the last published on Sunday, February 13, 2000, the day after his death, Schulz wrote, penciled, inked, and lettered by hand every single one of the daily and Sunday strips to leave his studio, 17,897 in all for an almost fifty-year run. No other single cartoonist has matched this achievement, but that is not what remains important about Peanuts.

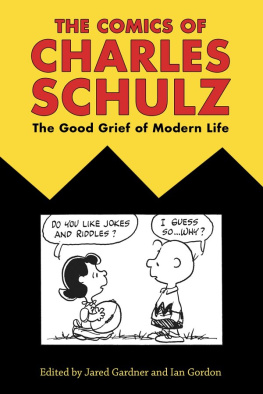

While cultural mavens have seldom granted the lowly comic strip aesthetic value, Schulz moved his feature in an artistic direction that was minimalist in style but richly suggestive in content. Any piece of art that endures, no matter the form or medium, draws on the cumulative traditions that have preceded it, and in turn reshapes and reinvigorates those traditions with new life and relevance for the future. Schulz did exactly that in Peanuts. His comic strip drew on a rich history of creative accomplishments in graphic humor and comic art and ultimately revived the comic strip as a relevant form that spoke to readers for the remainder of the twentieth century. He demonstrated its versatility in dealing with the social, psychological, and philosophical tensions of the modern world.

Charlie Brown and his friends were preoccupied with what has possessed and continued to obsess all of usthe relationship of the self to society, the need to establish our separate identities, anxiety over our neurotic behavior, and an overwhelming desire to gain control of our destinies. Charlie Brown appeals to us because of his resilience, his ability to confront and humanize the impersonal forces around him, and his unwavering faith in his ability to improve himself and his options in life. In his insecurities and defeats, his affirmations and small victories, Charlie is someone with whom we can identify. Through him we can all experience a revival of the spirit and a healing of the psyche. This has been Charles Schulzs amazing gift to the world through his small drawings appearing daily in the buried pages of the comic section of the newspaper. He was for the second half of the twentieth century our major pop philosopher, therapist, and theologian, and unlike Lucys booth, his shingle was always up.

In addition to his finely honed skills as a graphic artist, Schulz was also adept with the written word. Although he never fancied himself as a writer, and would normally rely on the cartoon image in conjunction with the word to convey his meaning, when given the opportunity, he produced a clear and straightforward prose that was admirable in its style and simplicity. He was frequently asked to give a talk or speech, produce an article for a magazine or newspaper, write an autobiographical essay for one of his anthologies, or comment on his chosen profession as a cartoonist. When he did so, the outcome was more often than not insightful and engaging in quality, and probably more revealing than anything anyone else has written about him and his work.

Schulzs major prose writings, both published and unpublished, have been gathered in this volume. Here the reader will learn, directly from the man himself, the facts of his early life and the development of his career. Here he talks about a wide variety of topics: the sources of his creativity and inspiration, how Peanuts came to be, the meaning of each character in the strip, his daily routine, how to do a chalk talk, how to achieve a career in cartooning, and the importance of his work in animation and television. There is a good deal here, as well, on a personal note: his work ethic, his philosophic attitude, and his religious beliefs which changed over time, until he would eventually call himself a secular humanist. His theories of humor emerge as well, as in his essay On Staying Power:

If you are a person who looks at the funny side of things, then sometimes when you are lowest, when everything seems totally hopeless, you will come up with some of your best ideas. Happiness does not create humor. Theres nothing funny about being happy. Sadness creates humor.

Despite the obvious depth of thought and maturity of attitude in Peanuts, Schulz did not consider himself an intellectual. Although he finished high school, he was largely a self-educated man who read widely and deeply in the great ideas and literature of the world. He was surprised when critics and college professors expressed interest in his work, but he held his own in conversations and interviews with them when they visited his studio to pay homage. He seemed to be regretful that he had not gone to college himself, and he greatly respected the academic and intellectual life. In the spring of 1965, Schulz signed up for a course in the novel at Santa Rosa Junior College under Professor Cott Hobart. As Schulz described the experience in his essay Dont Give Up:

Next page