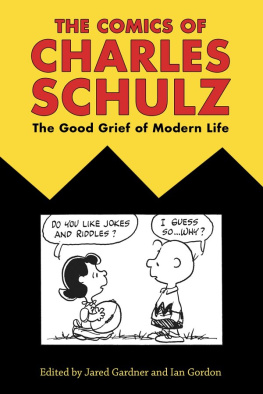

THE COMICS OF CHARLES SCHULZ

Critical Approaches to Comics Artists

David Ball, Series Editor

THE COMICS OF

CHARLES SCHULZ

The Good Grief of Modern Life

Edited by Jared Gardner and Ian Gordon

University Press of Mississippi Jackson

www.upress.state.ms.us

Designed by Peter D. Halverson

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Copyright 2017 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2017

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

Cloth | 978-1-4968-1289-6 |

Epub single | 978-1-4968-1290-2 |

Epub institutional | 978-1-4968-1291-9 |

PDF single | 978-1-4968-1292-6 |

PDF institutional | 978-1-4968-1293-3 |

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

This volume is dedicated to Jean Schulz, in profound gratitude for all she does for the preservation of her late husbands legacy and on behalf of comics.

CONTENTS

BEN SAUNDERS

ANNE C. McCARTHY

ROY T. COOK

LARA SAGUISAG

LEONIE BRIALEY

JEFFREY O. SEGRAVE

MICHAEL TISSERAND

JOSEPH J. DAROWSKI

CHRISTOPHER P. LEHMAN

BEN NOVOTNY OWEN

M. J. CLARKE

IAN GORDON

GENE KANNENBERG JR.

THE COMICS OF CHARLES SCHULZ

INTRODUCTION

JARED GARDNER AND IAN GORDON

There is in the history of American comics no strip more beloved or more familiar. Peanuts, it seems, has always been there. This holds especially true for the baby boomer generation. Beginning in October 1950 and still appearing in reruns seventeen years after the death of its creator, the strip is a hallmark of the second half of the twentieth century. Indeed, it is impossible to imagine newspaper comics pages without Peanuts, and even as newspapers themselves face the prospect of demise, it is clear that Schulzs creation will persistas it does alreadyin new media for generations to come. If anything, Peanuts seems to be going through a period of growth in the twenty-first century. For example, 2015 saw the release of The Peanuts Movie, with a new animated TV series debuting in 2016. And the Seattle firm Fantagraphics has recently completed its publication of the complete Peanuts, collecting the entire strip run for the first timewith the introduction to the final volume in the series written by none other than President Barack Obama. Like millions of Americans, I grew up with Peanuts, Obama writes, [b]ut I never outgrew it.1

As Garrison Keillor said: [T]here is not much in Peanuts that is shallow or heedless.2 Schulz famously wrote and drew the entire run of the strip himself without the aid of an assistant. For the best part of fifty years, after Schulz introduced a Sunday strip in 1952, he produced a comic strip every day. By contrast to this artisanal crafting of the strip, its impact grew to massive proportions, and at its height it appeared in 2,600 newspapers worldwide in an array of languages. Moreover, along with televised animated specials came a vast number of licensing and endorsement deals. While it might be tempting to see this state of affairs, with the disparity between the small scale of the strips production and its massive commercialization, as contradictory, it may be better to see it as one of the last vestiges of the Horatio Alger type of classic American success story. A hardworking midwesterner, the son of a hardworking barber, works diligently, retains his pride in work and his individuality throughout a long career, and enjoys spectacular success. Except, of course, Schulzs strip is so often about failure or thwarted desire, somehow having resisted ever becoming self-satisfied or complacent.

The strip has inspired countless acts of devotion over the decades. The director Wes Anderson, for example, includes allusions to Charlie Brown in all his films, and the series Arrested Development channeled the strip repeatedly in its first three seasons. Among the many cartoonists who cite Peanuts as a primary influence on their own careers are Bill Watterson, Gilbert Hernandez, Matt Groening, Paige Braddock, and Keith Knight. Indeed, the list could easily fill up an entire volume on its own, which is a major reason why it has always been easy to get cartoonists to write or talk about Peanuts for one of the many tribute volumes published over the decades, or for each of the twenty-five volumes of Fantagraphics collected Peanuts, whose introductions are written by such comics luminaries as Lynn Johnston, Garry Trudeau, and Tom Tomorrow.

Given the impact of Peanuts and its unparalleled influence on the history of American cartooning over the past sixty-seven years, one might expect a treasure trove of academic scholarship on Schulzs creation. But the truth is in fact very different. Even as the comics form has belatedly entered academic discourse in the most recent generation with a growing number of essays and books devoted to the graphic novel and to the history and analysis of everything from the American superhero comic book to Japanese manga to Franco-Belgian bande dessine, the number of peer-reviewed academic volumes and scholarly essays dedicated to Peanuts over the past twenty years can likely be counted on two hands.

There are several reasons for this, including the fact that newspaper comics more broadly have suffered considerable academic neglect in favor of the graphic novel and its cousins during this period. However, here a comparison to George Herrimans Krazy Kat is illuminating. As Michael Tisserand makes clear in his contribution to this volume, Herrimans strip was an important influence on Schulzs own, and while it never achieved the popularity of Peanuts, it was embraced as early as the 1920s as the prime example of the artistic potential of the comics form. Today, Herrimans strip is a frequent topic of academic analysis in papers and published essays, easily outpacing all rivals as the most analyzed newspaper strip in contemporary comics studies.

Part of the explanation for this disparity lies with Schulz himself and his unflagging refusal to be labeled an artist. In large measure, in declining such labels, Schulz was doing no more than fellow comic strip creators had done since the origins of the form. After all, newspaper comic strips are a form of mass entertainment, designed for the whole familys appreciation, for people from every walk of life. Their survival depended in no small part on not offending readers and editors, and on speaking simultaneously to readers coming to the strip for different reasons. Krazy Kat and Peanuts both did this exceptionally well, and both Herriman and Schulz ignored the courtship of the intellectual classes who would read deeper meanings into their work.

But even as Herriman fluently talked the talk of the humble craftsman, he was simultaneously traveling in the orbits of high modernism and the avant-garde such that his protestations always seemed to carry with them a wink for the knowing reader. When Herriman raised his hands in wonder, as he did with one fan in search of deeper meanings, at your strange interest in my efforts, one sensed an aw-shucks performance that was intended to be dismissed as performance.3 Not so with Charles Schulz. When he insisted that it is important to me to make certain that everyone knows that I do not regard what I am doing as Great Art, he meant it. He identified most strongly with craftspeoplepeople like his father, who ran a barbershop in Saint Paul for almost as long as the son would run his strip. Or like any one of the members of the adult world he saw coming into his fathers shop:

Next page