Names: Cruikshank, Dale P., author. | Sheehan, William, 1954 author.

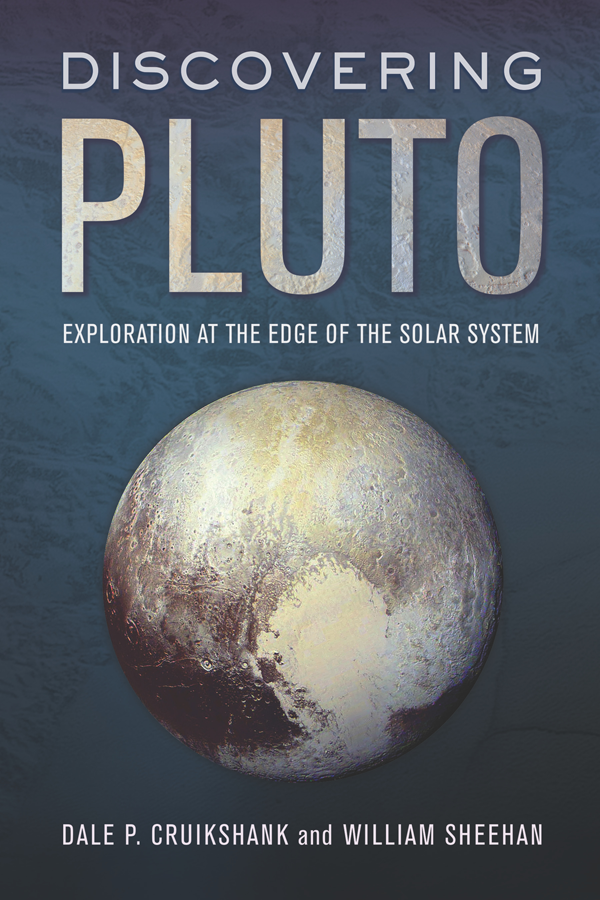

Title: Discovering Pluto : exploration at the edge of the solar system / Dale P. Cruikshank and William Sheehan.

Description: Tucson : The University of Arizona Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017047625 | ISBN 9780816534319 (cloth : alk. paper)

Classification: LCC QB701 .C78 2018 | DDC 523.49/22dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017047625

Preface

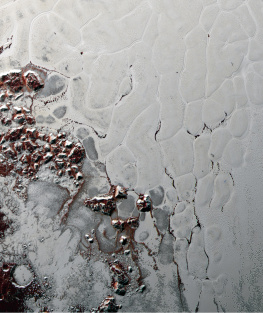

WITH THE NEW HORIZONS flyby of Pluto in July 2015, the Grand Tour of the Solar System, which began in the 1960s with the Mariner missions and continued with the Voyager flybys of the giant planets, was finally complete. Plutooriginally, when the Grand Tour was first conceived, the ninth major planet of the Solar Systemtogether with its anomalously large moon Charon and the four small satellites of their system, has been surveyed at close range. This book presents the long and fascinating history of searches of trans-Neptunian space by Percival Lowell and his colleagues that led to Clyde Tombaughs discovery of what seemed at the time to have been Lowells Planet X, and the subsequent gradual accumulation of facts about this small icy body on the inner edge of the Kuiper Belt. The book is brought up to date with a summary of the scientific results so far about this surprising world and a look forward to the next steps planned in the exploration of the Kuiper Belt.

Pluto, now classified as a dwarf planet but regarded as the ninth major planet of the Solar System from the time of its discovery by Tombaugh at Lowell Observatory in 1930 until it was reclassified by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in 2006, remainshowever classified, and despite its smallish size and distanceone of the most charismatic bodies in the SolarSystem. Except perhaps for Mars, no other planet seems of greater interest to the public.

Lowell first identified it as the incarnation of Planet X, a seven-Earth-mass major planet posited because of supposed residuals (unexplained differences between the theory and observed positions) of the planet Uranus. Astronomers hailed its discovery as a triumph of celestial mechanics similar to John Couch Adams and Urbain Le Verriers calculations leading to the discovery of Neptune in 1846and it arguably saved the famously broke Lowell Observatory from extinction. From the first, however, there were doubts about its mass and planetary status. By 1976, Dale Cruikshank, Carl Pilcher, and David Morrison discovered methane ice on Pluto. From then on it was clear that Pluto was much too smallonly about 2,000 km in diameter, or smaller than Earths Moonto have exerted any significant perturbations on the giant planets Uranus or Neptune. The discovery of the largest of its five satellites, Charon, by James Christy at the U.S. Naval Observatory two years later furnished a precise value of the mass.

Since those 1970s discoveries, it was learned that Pluto is a particularly outsized member of the expanse of icy bodies on the edge of the outer Solar System called the Kuiper Belt. Rather than being, as once thought, a major planet in a relatively simple collection of planets, Pluto is representative of a part of the Solar System that contains some two thousand known objects. It is a mini-world or, to use the IAUs nomenclature, a dwarf planet. It and its Kuiper Belt congeners (as well as bodies belonging to the still more distant Oort cloud) point to a Solar System in a state that was once vastly different from what it is now.

This book falls naturally into two parts. Though both authors contributed to all the chapters, the first eight were primarily the work of coauthor Sheehan, while the remaining twelve were chiefly written by coauthor Cruikshank. Cruikshank was a graduate student of Gerard Kuiper and later a planetary scientist specializing in the investigation of the icy outer worlds of the Solar System, and he has had an insider view of the recent science as an investigator on the New Horizons mission.

Acknowledgments

THE AUTHORS WISH to thank the many individuals and institutions that have generously supported their research. In his research of archival materials and for discussions of the events leading to the discovery of Neptune, coauthor Sheehan thanks Brian Sheen and Norma Foster, who helped provide understanding of and guidance to important sites and resources related to John Couch Adamss Cornish roots, and the Truro Public Records Office, which provided some significant Adams documents. There were many discussions and, in some cases, Neptune-related travels with Neptunians Craig Waff, Nick Kollerstrom, Dennis Rawlins, David Dewhirst, Sir Patrick Moore, Richard Baum, Robert W. Smith, Roger Hutchins, and Allan Chapman. Adam Perkins of Cambridge University Library kindly provided assistance in accessing George Biddell Airys Neptune file and James Challiss papers. The librarian of St. Johns College, Cambridge, provided access to the papers of John Adams and his student Ralph Sampson, and Peter Hingley of the Royal Astronomical Society was helpful in more ways than we can name.

James Lequeux, the biographer of Urbain Le Verrier, provided much assistance with the French side of the Neptune discovery saga, while Franoise Launay was always ready at a moments notice to provide advice and support. Jacques Laskar and Gregory Laughlin provided useful insights and adviceinto perturbation theory, while Professor Kenneth Young and H. M. Lai are thanked for correspondence related to their 1990 paper, with C. C. Lam, on the perturbations of Uranus by Neptune.

Special Collections at the Howard-Tilton Memorial Library of Tulane University and Howard Plotkin provided guidance and documentation on W. H. Pickerings planet searches. On Percival Lowell and Planet X, Robert Burnham Jr., who spent countless hours on the blink comparator at Lowell Observatory comparing plates taken in the Planet X search with later plates in the search for stars of large proper motions, was an early inspiration; William Graves Hoyts pioneering researches provided a high standard for those who came afterward, while Arthur A. Hoag generously supported coauthor Sheehans initial reconnaissance in the Lowell Observatory Archives. The staff of the Houghton Library of Harvard University was a pleasure to work with; Lowell historians, librarians, and preservationists Antoinette Beiser, Lauren Amundsen, Kevin Schindler, and Michael and Karen Kitt were not only professionally helpful but became close friends.

The Lowell Observatory is to be warmly thanked for its generosity in providing photographs from its collection. William Lowell Putnam, the sole trustee of the Lowell Observatory, offered insights into Percival Lowell, his family, and his father, Roger Lowell Putnam, who was sole trustee at the time Pluto was discovered. He also commented in detail on a draft of , while Bradford A. Smith, his long-time collaborator at New Mexico State University, furnished many insights into Tombaughs work at Lowell and after. As principal investigator of the Voyager imaging team, Brad also offered some of his recollections about that epic voyage of outerSolar System exploration. James W. Christy and his wife, Charlene, were interviewed at length in their Flagstaff, Arizona, home, and gave an interview, full of little-appreciated details, about the discovery of Charon.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).