Text: Nathalia Brodskaa

(except the poems and TheManifesto of Symbolism by Jean Moras)

Maurice Maeterlinck, Serres chaudes, Succession Maeterlinck

Saint-Pol-Roux, Tablettes, Rougerie

Paul Valry, Posies, Gallimard

Translation: Tatyana Shlyak and Rebecca Brimacombe (Text)

Eamon Graham (Poems except Correspondances and Spleen of Charles Baudelaire by Lewis Piaget Shanks)

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

4 th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

Emile Bernard, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Boleslas Biegas

Jean Delville, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ SABAM, Brussels

Maurice Denis, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

James Ensor, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ SABAM, Brussels

Lon Frdric, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ SABAM, Brussels

Adria Gual-Queralt

Wassily Kandinsky, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Frantiek Kupka, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Henri Le Sidaner, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Aristide Maillol, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Pierre Amde Marcel-Berronneau

Edgar Maxence, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Jzef Mehoffer

Georges Minne, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ SABAM, Brussels

Edvard Munch, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ BONO, Oslo

Alphonse Osbert, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Kosma Petrov-Vodkine

Lon Spilliaert, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, USA/ SABAM, Brussels

Nstor de la Torre

Stanislas Ignacy Witkiewicz

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world.

Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78310-398-0

Nathalia Brodskaa

Symbolism

Contents

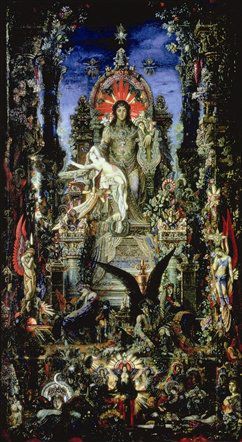

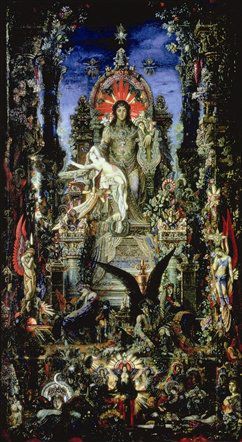

Gustave Moreau, Jupiter and Semele, 1895.

Oil on canvas, 213 x cm .

Muse national Gustave-Moreau, Paris.

Introduction: The Manifesto of Symbolism by Jean Moras

For two years, the Parisian press has been much occupied by a school of poets and prosateurs known as the Decadents. The storyteller (in collaboration with Mr Paul Adam, the author of Self) of Le Th chez Miranda, the poet of the Syrtes and the Cantilnes, Mr Jean Moras, one of the most visible among these revolutionaries of letters, has formulated at our request, for the readers of the Supplement, the fundamental principles of the new manifestation of art.

(Le Figaro, literary supplement, September 18, 1886)

SYMBOLISM

Like all arts, literature evolves: a cyclical evolution with strictly determined turns which become complicated by various modifications brought about by the march of time and the upheavals of surroundings. It would be superfluous to point out that each new evolutionary phase of art corresponds exactly to senile decrepitude, to the inevitable end of the immediately previous school. Two examples will suffice: Ronsard triumphed over the impotence of the last imitators of Marot, Romanticism spread its banners over the Classical debris that was poorly guarded by Casimir Delavigne and tienne de Jouy. It is that every manifestation of art fatally manages to impoverish itself, to exhaust itself; then, from copy to copy, from imitation to imitation, what was once full of sap and freshness dries out and shrivels up; what was the new and spontaneous becomes the conventional and the clich.

And so Romanticism, after having sounded every tumultuous alarm of revolt, after having had its days of glory and battle, lost its strength and its grace, abdicated its heroic audacities, made itself orderly, sceptical and full of good sense: in the honourable and paltry attempt of the Parnassians it hoped for deceptive revivals, then finally, like a monarch fallen in childhood, it let itself be deposed by Naturalism, to which one can only seriously grant a value of protest, legitimate but ill advised, against the dullness of some then fashionable novelists.

A new manifestation of art, therefore, was expected, necessary, inevitable. This demonstration, incubated for a long time, has just hatched. And all insignificant anodynes of the joyful in the press, all the concerns of serious critics, all the bad temper of the public, surprised in its sheeplike nonchalance, only further affirm every day the vitality of the present evolution in French letters, this evolution noted in a hurry by judges, by an incredible discrepancy, of decadence. Notice, however, that the Decadent literature proves essentially to be tough, long-winded, timorous and servile: all the tragedies of Voltaire, for example, are marked by these specks of Decadence. And with what can one reproach, when one reproaches the new school? The abuse of pomp, the queerness of metaphor, a new vocabulary or harmonies combining themselves with colours and lines: characteristics of any renaissance.

We have already proposed the name of Symbolism as the only one capable of reasonably designating the present tendency of the creative spirit in art.

It was mentioned at the beginning of this article that the evolution of art offers an extremely complicated cyclic character of divergences: thus, to follow the exact filiations of the new school, it would be necessary to go back to certain poems of Alfred de Vigny, back to Shakespeare, back to the mystics, further still. These questions would demand a whole volume of commentaries; therefore, let us say that Charles Baudelaire must be considered as the true precursor of the current movement; Stphane Mallarm allots to it the sense of mystery and the ineffable; Paul Verlaine broke in his honour the cruel hindrances of verse that the prestigious fingers of Thodore de Banville had previously softened. However, the supreme enchantment is not yet consumed: a stubborn and jealous labour requires newcomers.

As the enemy of plain meanings, declamation, false sentimentality and objective description, Symbolic poetry seeks to clothe the Idea in a sensual form which, nevertheless, would not be its goal in itself, but which, while serving to express the Idea, would remain exposed. The Idea, in its turn, must not be deprived of external analogies; because the essential character of Symbolic art consists of continuing until the concentration of the Idea in itself. Thus, in this art, scenes from nature, the actions of humans, and all concrete phenomena cannot manifest themselves for their own sake; here they are the sensual appearances intended to represent their esoteric affinities with primordial ideas.

The accusation of obscurity thrown in fits and starts by readers against such an aesthetic has nothing which can surprise. But what to do? The