Vladimir Mayakovsky and THATS WHAT

The long love poem called here Thats What is entitled in Russian Pro Eto , which literally means About This, with the strong suggestion that the author felt the need to defend himself against the criticism that had come his way for the irregular nature of his unconventional love-life. Typically, the Russian words carry echoes of the words for poet and proletarian as well as expressing a characteristic off-hand defiance which is a sort of protective colouring. Love, the class struggle, technological change and the creative process itself all fuse together in what George Hyde identified, in his translation of Mayakovskys How Are Verses Made (1926), as the expanded metaphors typical of this poets work. Indeed, Mayakovskys elaborate incremental metaphors and metonymies reflect, in this poem as in all his work, the creative fascination with sound and form and linguistic metamorphosis and variation that made him a sort of poets poet, the doyen, if not the envy, of other poets (Pasternak, for example) who by no means shared his revolutionary political convictions and commitments. Mayakovskys empathy with the urban poor was born of experience.

The son of a forest ranger, born in 1893 in Georgia, he was forced to move with his family to Moscow after his fathers sudden death. The world of rented rooms and poverty, intensified subsequently in Thats What by communist Moscows painful attempts to catch up with modernity, is matched by the creativity of a brilliant artistic imagination engaging in its own way with the verbal and visual experiments of Futurism, Constructivism, Formalism and the host of other feverishly creative isms that have made Russian Modernism so powerfully influential in world art. In the winter of 1913-1914 the Futurists, with whom Mayakovsky identified, had toured Russia, reading their work to large and sometimes hostile audiences. Mayakovsky, with his huge build, huger voice and flamboyant clothes, was himself a slap in the face of public taste, (the title of a Futurist manifesto) and revelled in the role, which he went on to combine with his own unique formulation of the unfallen spirit of the revolution. His extremely personal style was developing rapidly. He hated fine writing, prettiness and sentimentality, and went to the opposite extreme, employing the rough talk of the streets, deliberate grammatical heresies and all kinds of neologisms, which he turned (in HVM ) into a compendium of revolutionary rhetoric aimed at aesthetic victory in the class war.

He wrote much blank verse, but also made brilliant (almost untranslatable) use of a rich variety of rhyme schemes, assonance and alliteration, creating complex patterns. His rhythms are powerful but irregular, departing from the syllabo-tonic principle of Russian versification, and based on the number of stressed syllables in a line, rather like Hopkinss dynamic-archaic sprung rhythm, and influenced by Whitman and Verhaeren. In his public readings, he would often declaim in a staccato thats what take-it-or-leave-it style, indicated typographically by the use of very short lines, spilling down the page in a distinctive staircase shape which also turns into a narrative principle, analysed by Victor Shklovsky: Hey, you! You fine fellows who Dabble in sacrilege In crime In violence! Have you seen The most terrible thing? My face, when I Hold myself calm?

Strangely akin to modern rock poetry in its erotic thrust and bluesy complaints and cries of pain, not to mention its sardonic humour, Mayakovskys poetry is aggressive, mocking and tender all at once, and often fantastic or grotesque. His imagery is violent and hyperbolic he speaks of himself (for example) as vomited by a consumptive night into the palm of Moscow. The figure of Mayakovsky himself towers at the centre of his poems, martyred by fools and knaves, betrayed by love, preposterous or tragic, abject or heroic, but always larger than life, a giant among midgets. Characteristically, his first book, a collection of four poems published in 1913, was called Ya (I).

In his autobiographical tragedy Vladimir Mayakovsky (1913), he portrayed the poet romantically as a prophet in heroic conflict with the banality of everyday life (the Russian word for this is byt, and it recurs in his suicide poem.) It played to packed houses despite exorbitant ticket prices. After the revolution, Mayakovskys poetry, like Meyerholds theatre, spoke directly to huge proletarian audiences. It was Meyerhold who staged (in 1918) Mayakovskys Mystery-Bouffe , a typically subversive and blasphemous rewriting of the story of Noah reaching his promised land. The epic narratives of travel and escape that figure so prominently in Thats What are prefigured in the epic (or mock-epic) poem about American interventionism entitled 150,000,000 (1919-1920), in which the folk-hero Ivan fights a hand-to-hand battle with Woodrow Wilson, resplendent in a top hat as high as the Eiffel Tower. Folk tale and political satire fuse in the name of the proletariat (the hundred and fifty million Soviet citizens.) His most popular poem among present-day Russian readers, however, is undoubtedly the pre-revolutionary Oblako v Shtanakh (The Cloud in Trousers, 1915). Its dramatic gestures of despair at being rejected by Maria, his lover, (actually a composite figure), prefigure the more complex and extended masochistic narratives of humiliation and defeat in Thats What .

In both poems the poets suffering grows to become a paradigm of all the rejection and dispossession in the world, and his rage swells to encompass art, religion and the entire social order, until he is threatening to bring the whole world crashing down in revenge for his failure in love, and the social conspiracy which has cheated him of the object of his overwhelming (Oedipal?) desire. The intensity of these emotions carried him close to madness, and found its objective correlative in the creative and destructive energies of the revolution. George Hyde discusses in his and echoed in many sequences of Thats What . She did not reject him, but neither did she reciprocate his immoderate love, or give up other admirers. For sixteen years Mayakovsky publicly lamented Lilys coldness and inconstancy, beginning just a few months after their first meeting with The Backbone Flute (1915). But what he really wanted from her, at the end of the day, it would be hard to say.

All of this disproportionate, insatiable orality helps us to understand why Mayakovsky welcomed the Russian revolution as my revolution and why he resisted (as he does in Thats What ) the reforms introduced by Lenin when the communist leader recognised that (to put it bluntly) Soviet Socialism, which seemed such a good idea and had cost so much in ruined lives and shattered dreams, did not actually work. We may discover here also why the equally unwelcome reforms of Stalins first Five Year Plan (1929), an act of naked authoritarianism, should have supervened destructively upon Mayakovskys erotic confusion and prompted his suicide in 1930. During the 1920s he had made several trips abroad, including a long visit to America in 1925, which might be interpreted as a hopeless bid to escape from Lily, and where a new love affair climaxed with the birth of his child. Like Hart Crane, Mayakovsky wrote a poem extolling Brooklyn Bridge as the great symbol of modernity and the free human spirit, but he was also deeply troubled by the social inequalities and the racism he found in the America of the time. On his return to the USSR after two years, he wrote the long poem Khorosho! (Okay!), a sincere tribute to his communist homeland, while his relationship with Lily continued to form an inexorable counterpoint to everything else, weaving its way through his urbanism, his political commitments and his self-dramatising scrutiny of the creative process. The intensity of the desire formulated in the earlier poem with the Russian title Lyublyu the word for I love, containing the letters that spell the name of his beloved, Lilya Yurevna Brik is complemented now by the agonising parables of separation and betrayal of Thats What .

2009

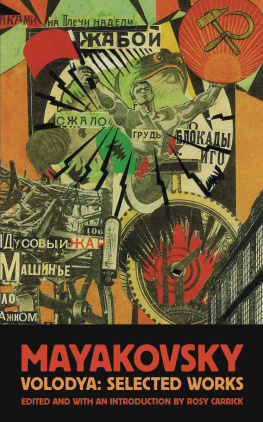

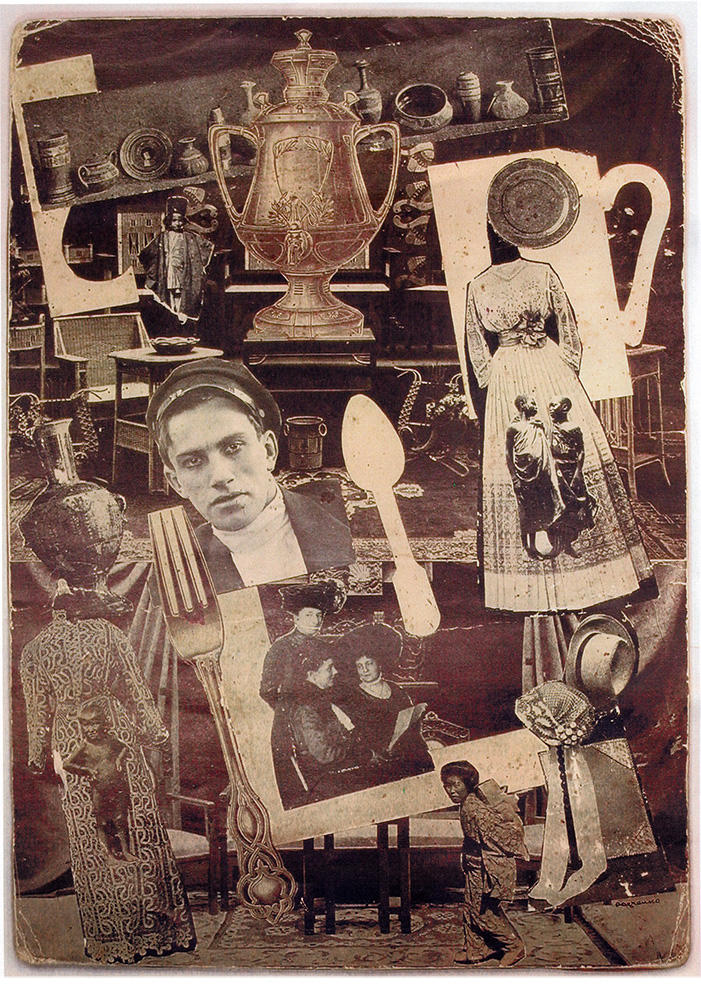

2009 Although Alexander Rodchenko produced the above illustration [untitled] as part of his series of photomontages for Pro Eto Thats What , it did not appear in the first published edition.

Although Alexander Rodchenko produced the above illustration [untitled] as part of his series of photomontages for Pro Eto Thats What , it did not appear in the first published edition.