new directions titles available as ebooks

ndbooks.com

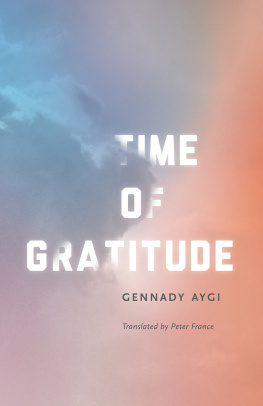

Time of Gratitude

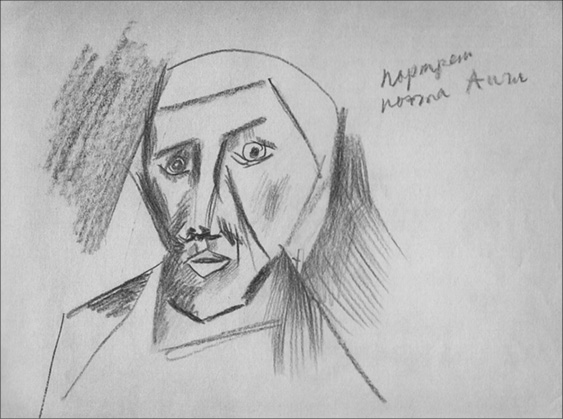

Portrait of Gennady Aygi by Vladimir Yakovlev, 1973. Used with the permission of Ilya Umansky.

Copyright 1975, 1976, 1982, 1989, 1991, 1993, 1994, 1998, 2001 by Gennady Aygi

Copyright 2017 by Galina Borisovna Aygi

Copyright 1982, 1991, 1997, 1999, 2007, 2009, 2017 by Peter France

All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, television, or website review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

Manufactured in the United States of America

New Directions Books are printed on acid-free paper

First published as a New Directions Paperbook ( ndp 1394) in 2017

Design by Eileen Baumgartner

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Agi, Gennadi, 19342006, author. | France, Peter, 1935 translator.

Title: Time of gratitude / Gennady Aygi ; translated from the Russian by Peter France.

Description: New York : New Directions Publishing Corporation, 2017. |

New Directions paperbook original. | Collection of poems and essays.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017014036 | ISBN 9780811227193 (alk. paper)

Classification: LCC PG3478.I35 A2 2017 | DDC 891.71/44--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017014036

eISBN: 9780811227209

New Directions Books are published for James Laughlin

by New Directions Publishing Corporation

80 Eighth Avenue, New York 10011

ndbooks.com

Translators Preface

Night is the best time for believing in the light. These words, attributed to Plato, are the epigraph to Time of Gratitude, a cycle of poems composed in 197677 by the Russian and Chuvash poet Gennady Aygi. They mark the emergence from a particularly dark period in the poets life following the politically inspired murder of his friend, the poet and translator Konstantin Bogatyrev an emergence helped, as Aygi wrote more than once, by the example and inspiration of fellow writers from many countries. Aygi doesnt appear to have suffered greatly from the anxiety of influence, and was very much a poet of gratitude, gratitude for the human and natural world, gratitude for the artistic creations of others. It seemed appropriate, therefore, to use this same title for a collection of tributes he wrote for some of the writers who meant the most to him, who enabled him to survive the spiritual and material hardships of a dark age in Russian life.

Gennady Nikolaevich Aygi (19342006) was the son of a village schoolteacher in Chuvashia, a non-Russian republic nearly 500 miles to the east of Moscow. His mother, a peasant woman, was the daughter of the last pagan priest of his village. After studying at the Literary Institute in Moscow and working for ten years at the Mayakovsky Museum, he lived and wrote in the literary underground, remaining unpublished and unrecognized in Russia until the perestroika of the late 1980s. Thereafter, he became the Chuvash national poet, but it was as a Russian poet that he became known and published throughout the world and eventually, after a long wait, in Russia. The English-speaking world was behind continental Europe in recognizing Aygis importance, but several volumes of his poems have appeared in Britain and America over the years. In the introductions to two of them, Selected Poems 19541994 (Angel Books, London, and Hydra Books, Evanston, IL, 1997) and Child-and-Rose (New Directions, New York, 2003), I give a general account of Aygis work and career. Child-and-Rose also contains two important aphoristic essays on poetry, Sleep-and-Poetry and Poetry-as-Silence, while a successor volume, Field-Russia (New Directions, New York, 2007) includes an important interview on poetry titled Conversation at a Distance. These would provide a helpful background to the discussion that follows, where I focus on Aygis involvement with the writers and painters to whom these tributes are addressed.

For Aygi, poetry was a calling, a commitment of the greatest seriousness. Even so, in an interview of 1985, he remarked: In general I regard great prose as the highest form of verbal art. He knew himself to be a poet, which was not the same as a writer indeed, he described himself as a non-writer. As a result, though he wrote many letters a remarkable body of writing that should one day be collected he was always reluctant to write publicly in prose: essays, memoirs, and the like. The texts gathered here were almost all written in response to pressing requests, for particular circumstances, anniversaries, deaths, special numbers of journals, new publications, etc. In a few cases, notably the text on Paul Celan, For a Long Time: Into Whisperings and Rustlings, the prose is really a poem. And I have thought it worthwhile to intersperse the prose texts with actual poems, either because these are the only tributes he left to much-loved authors (Baudelaire, Norwid), or because the poems illustrate and illuminate the prose (as with those dedicated to Celan, Shalamov, and Char).

Reading Aygis poems, one is struck by the frequency of dedications, quite often enigmatic, simply initials. They are addressed both to personal friends (all over the world) and to artists and writers, both living and dead. There is nothing unusual about this of course, but it is worth stressing that for Aygi poetry was essentially communication, the writing and reading of poetry creating scattered communities of people who could share a vision, a common search. This community crossed language barriers. Aygi himself worked closely with his translators, and he translated poetry from many languages into Chuvash.

It is worth stressing too that this village boy (and he did in fact remain a village boy in many ways until the end of his life, when he was buried in the snowy fields of Shaymurzino) became a citizen of the world republic of letters, a person of wide and deep culture. His poetry may lie outside the mainstream of Russian poetry as conventionally understood, but it creates its own tradition in which his native Chuvash culture (largely an oral culture until the end of the nineteenth century) flows together with European modernism (Nietzsche, and more lastingly, Kafka and Kierkegaard), the poetry of France, and the great Russian artistic movements of the early twentieth century. To these we can add (among others) many figures from earlier Russian poetry (one might mention Lermontov, Batyushkov, and Annensky), Russian prose writers of the twentieth century (notably Platonov and Shalamov), biblical and liturgical texts, religious thinkers and in the English-language world (though none of them appear in this volume), the revered figure of Dickens and poets such as Emily Dickinson and Gerard Manley Hopkins, insofar as they could be found through translation. At the same time, Aygi, who lived for a good part of his life in an underground world of writers, artists, and musicians, was much influenced by the other arts, notably the painters and musicians of the twentieth century with Malevich as the central figure but also, over a long period, the much beloved Schubert, who figures in many of his poems.