Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The impetus behind this project emerged from conversations I had with a former Catholic priest about the relationship between the quest for the historical Jesus and the Christ of faith in Mikhail Bulgakovs novel, The Master and Margarita, which I was teaching for the first time in my Soviet literature class. Though the historical critical method of biblical scholarship and aspects of Western and Eastern Christology occupied many of our conversations, our dialogue began with one of the first questions Woland asks his two atheist interlocutors on that park bench at Patriarchs Ponds: the question about the five proofs of God. Curiously, neither of the two most recent and well-regarded translations of the novel had any annotations explaining what these proofs were, though presumably many readers might not know who authored them or be able to recall them. My interlocutor could, and without any prompting elaborated on them at length. That priest was my stepfather, and in listening to him recount Thomas Aquinass Five Ways and in talking with him about what Bulgakov was up to having the devil not only insist on Gods existence but that of Jesus as well, I realized I had found an endlessly fascinating subject. Calvin Schwenk, a priest forever in the line of Melchizedek, is thus this studys most important inspiration and guiding light, though he did not live to see its completion. I offer this book in his memory and that of my mother.

I have many other debts to acknowledge, large and small. My colleague, Anna Maslennikova, formerly of Saint Petersburg State University, carefully read every page of my manuscript and offered innumerable insights and suggestions as well as constant support throughout the writing process. Her comments and those of my anonymous readers were crucial in honing my arguments and saving me from missteps and I thank them all for their valuable critical interventions. Other important readers of this manuscript include Gary Saul Morson and Kathleen Parth, who provided many helpful and insightful comments at different stages of writing and revision. My book is better for the contributions of all of these thoughtful commentators, though any mistakes that persist are strictly my own responsibility.

All of the case studies in my book were presented in one form or another at annual meetings of the Midwest Slavic Conference or the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies, and I thank those organizations for providing such stimulating environments for the airing of scholarly ideas. I thank as well everyone at these conferences who engaged with my ideas and helped me develop them. An early and fruitful forum for my work in this area was a one-day symposium at the Memorial Art Gallery at the University of Rochester on the authority of the image in Russian and Soviet culture in November 2008. I thank Marlene Hamann-Whitmore, McPherson Director of Academic Programs, and Nancy Norwood, curator of European art, for inviting me to participate. My former PhD student and present colleague in the field, Elena Rakhimova-Sommers of the Rochester Institute of Technology, also organized a one-day symposium on Russian culture where I presented on portions of my book in April 2013 in the most supportive and convivial of academic settings, and I thank her as well.

My thanks also to Peter Lennie, dean of faculty at the University of Rochester, who supported a leave request in the spring of 2009 that got the book off to a good start, and to my research assistant, Katharina Schander, for her thorough and professional help in my final year of work on the manuscript. My literature students at UR, especially those in my image of Christ class, were generous interlocutors on many of the questions I treat in this book and I am grateful for their enthusiasm and interest. One of these students in particular, Meaghan DeWaters, deserves special mention. Meaghan wrote an impressive 187-page honors thesis in 2011 on the pathological believer in Dostoevskys fiction. Her interest in the relationship between illness and apophaticism in the writers metaphysical inquiries was the basis for a fruitful dialogue between us on the riches of the apophatic approach to spirituality, a key element in my own approach to my subject. Ryan Prendergast in my home department at the University of Rochester and Michael Ruhling at the Rochester Institute of Technology provided both support and intellectual dialogue throughout the writing process and I thank them for their insights, collegiality and friendship.

At Northern Illinois University Press I am grateful to acquisitions editor Amy Farranto and Orthodox Studies Series editor Roy Robson for their generous support and help throughout the review process. My sincere thanks as well to my manuscripts superb copyeditor, whose keen editorial eye and pitch-perfect ear for language improved my book in its final revision, and to managing editor Nathan Holmes, who shepherded me through the copy-editing phaseand oversaw all apects of production. My manuscript improved immeasurably under their collective guidance and I could not have asked for a more professional and nurturing publishing process.

My twin brother Jim has always been a pillar of supportmy stave and my staff, as Turgenev might have put it. His interest in my work and encouragement have been a sustaining presence over the years. Though she did not sew me a cap with the letter M on it like Margarita did for her favorite author, my wife Laura was this manuscripts most jealous defender and zealous supporter. She made our basement officelike the Masters basement apartmenta refuge of creative work and like Margarita is far more important to the plot than the author. I dedicate this book to our children, Anna and Will, who grew up watching their father at his computer, writing and rewriting. They kept me grounded in the real world and constantly reminded me that there were other joys to my life besides books.

Parts of this book have appeared elsewhere in altered form. Portions of chapters 2 and 5 appeared as Tolstoys Jesus versus Dostoevskys Christ: A Tale of Two Christologies, in From Russia, with Love Symposium Proceedings (Rochester: Rochester Institute of Technology, 2014), 1326. Chapters 3 and 4 appeared in different versions as, respectively, A Narrow Escape into Faith? Dostoevskys Idiot and the Christology of Comedy, Russian Review 70, no. 1 (January 2011): 95117, and Divine Love in War and Peace and Anna Karenina, Zapiski russkoi akademicheskoi gruppy v S.Sh.A/Transactions of the Association of Russian American Scholars in the USA 34 (2010): 16590. They are reprinted here with the kind permission of these journals.

INTRODUCTION

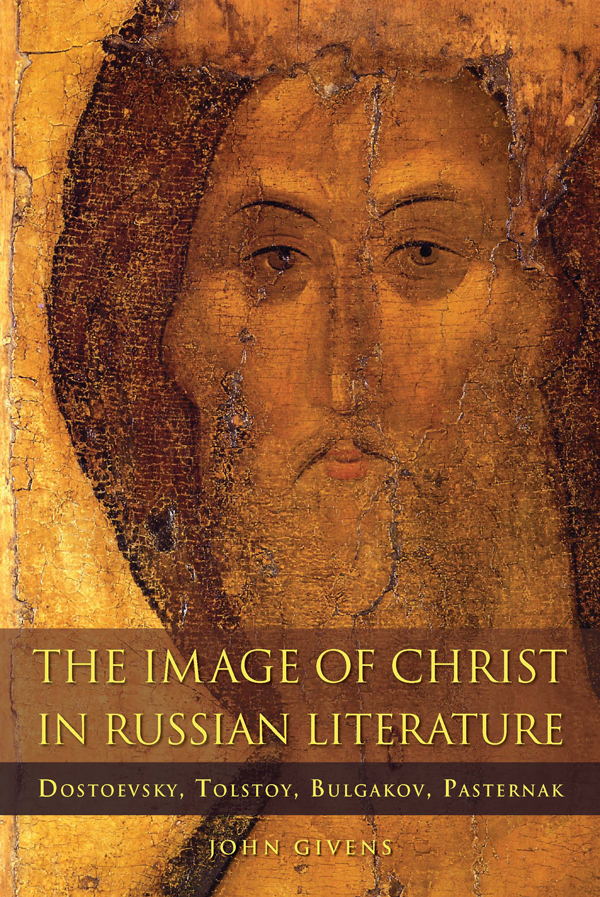

THE IMAGE OF CHRIST AND RUSSIAN LITERATURE

Let us preserve the image of Christ, that it may shine forth like a precious diamond to the whole world... So be it, so be it!

Fyodor Dostoevsky, Brothers Karamazov (Pevear and Volokhonsky translation)

If you were to read only the works of Fyodor Dostoevsky after his Siberian exile or Leo Tolstoy in his final thirty years, you might easily believe that Jesus Christ and Russian literature are two subjects that cannot be separated from each other, so central does Christ or his teachings seem to be in their lives and creativity. The reality, of course, is quite different. Russian literature of the past two hundred plus years is as secular as any of the literatures of its European neighbors. And yet, at the same time, like European literature, Russian literature was nurtured and developed in a culture whose art, spirituality, and thought were dominated for centuries by the image of Jesus and the beliefs and practices of the Christian faith. Indeed, as far as Russian literature is concerned, we may even argue that in its earliest formsnumerous sermons and saints livesthere was no literature without Jesus, for these works dealt with little else than living in accordance with the words and deeds of Christ.