This edition first published in hardcover in the United States and the United Kingdom

in 2014 by Overlook Duckworth, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

N EW Y ORK

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales, please contact , or write us at the address above.

L ONDON

30 Calvin Street

London E1 6NW

www.ducknet.co.uk

For bulk and special sales, please contact , or write us at the above address.

Copyright 2009 by Oleg Dorman

Translation copyright 2014 by Polly Gannon and Ast A. Moore

Credits for illlustrations can be found on .

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN: 978-1-4683-1111-2

BY O LEG D ORMAN

T HIS BOOK IS THE TRANSCRIPT OF AN ORAL ACCOUNT BY L ILIANNA Zinovievna Lungina of her own life, which was presented in a documentary series called Word for Word. Ive added the most minor corrections, which are standard in the publication of any transcript, and have added those parts of the stories that could not, for various reasons, make it into the film, so the book is about a third longer than the series.

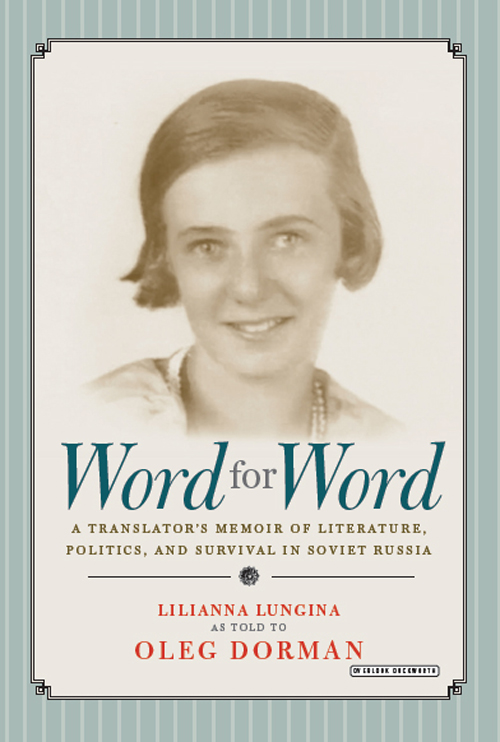

Lilianna Lungina (19201998) was a celebrated literary translatorit was through her translations that Russian readers discovered Astrid Lindgrens Karlsson on the Roof and the novels of Knut Hamsun, August Strindberg, Max Frisch, Heinrich Bll, Michael Ende, Colette, Alexandre Dumas, Georges Simenon, Boris Vian, and Romain Gary. She translated the plays of Friedrich Schiller, Gerhart Hauptmann, and Henrik Ibsen, and stories by E. T. A. Hoffmann and Hans Christian Andersen.

At the very beginning of the 1990s, a memoir by Lilianna Lungina, Les saisons de Moscou (The Seasons of Moscow), was published in France; it became a bestseller, and in an annual poll conducted by Elle, it was named by French readers as the best nonfiction book of the year. But Lungina was determined not to publish the book in Russia. She believed that her compatriots needed a completely different book, entirely rewritten from cover to cover. With ones own people, she explained, one can and must discuss the things that outsiders cannot understand.

And at a certain point, she agreed to take on this challenge in front of a television camera. I think that the French book was something like a first draft for her story, which stretched over many days. In February of 1997, over the span of a week, I came to Lunginas apartment on Novinsky Boulevard with the cinematographer Vadim Yusov and a small camera crew to listen to and film an oral novel, which would become the film Word for Word.

In her long life, Lilianna Lungina lived in many countries and captured the twentieth century with an extraordinary depth and clarity. This was a century that confirmed that there is no such thing as a collective lifeonly the lives of individuals. A century that confirmed that one is the only soldier on the fieldthat, indeed, that one is, himself, that field. That a person isnt the plaything of circumstances, nor lifes victim, but a boundless and impregnable source of good.

Few people in the world get the chance to meet people like Lungina and her husband, the famous screenwriter Simon Lvovich Lungin. And yet its possible that other peoplethe people one meetsare the most important thing in our lives. It is through other people that we can take stock of life, of what human capability, of what love can be, of whether loyalty, bravery, and truth truly resemble what is written about them in books.

I was lucky enough to know and love such people. It is an honor for me to present this book to you.

M Y NAME IS L ILYA L UNGINA . F ROM AGE FIVE TO TEN, WHEN I LIVED in Germany, I was called Lili Markovich, stress on the first syllable. Then, from age ten to fourteen, in France, they called me Lily Markovichstress on the last syllable. And when I performed in my mothers puppet theater, I was called Lily Imali. Imali is my mothers pseudonym. It is an ancient Hebrew word that means my mama. Thats how many different names Ive had. I studied in as many schools as I had names. I was enrolled in twelve schools, all told. After such a long lifeon the 16th of June, 1997, I will be 77 years old; even thinking about it sends shivers down my spine! I never thought I would live to such a venerable ageafter such a long life, I have still never learned to refer to myself by my name and patronymic. Maybe this is a mark of our generation. We have always thought of ourselves as young, and so avoided formal forms of address.

Still, seventy-seven is a ripe age, and its time to start drawing conclusions about what has happened during my time. And not just provisional conclusions, as my husband Sima called the last chapter of his book Seen and Believed, but final ones. On the other hand, though, what kinds of conclusions can you draw about an activity, about a vocation? What kinds of conclusions are there to be drawn about life? The results of life are life itself, I think. The entire sum of happy, trying, unhappy, bright, and bland moments you live through is the essence of life. That is the conclusion, the only one that matters. Thats why I now want to look back and reminisce. Thats why I feel drawn to old photographs.

I remember very clearly the moment I realized that I was myself, separate from the rest of the world.

I have a photograph in which Im sitting on my fathers lapthat was the very moment Im talking about. I loved my father dearly and was terribly spoiled by him. Up to that very second, I had felt I was fused with him and the whole world. Suddenly I had the sensation that I stood apart from him and from everything around me. I think it was the consciousness of being a person in my own right. Until that moment I grew willy-nilly, programmed by my genes, by what was already innate in me from birth. But once I realized that I was separate from the world, it began to influence me, to act upon me. And what was innate in me began to undergo changes, to be refashioned and refined, to be subjected to the larger life that surrounded me. In other words, my experiences, the situations I found myself in, the choices I made, the relationships I formed with othersin all of this, the world that raged around me became ever more palpable. This is why I thought that when telling about my life I would be talking not so much about myself, but It seemed rather presumptuous at firstwhy should I start talking about myself? I dont consider myself to be smarter or wiser than the next person. It just didnt make sense to talk about myself. But to talk about myself as some sort of organism that absorbed elements of the external world, the complex, very contradictory life of the world outsidemaybe its worth a try. Then you would end up with the experience of that larger life filtered through one person, something more objective within the personal. And that may turn out to be worthwhile.

It seems to me that now, at the end of the century, when our country is in the midst of such confusion and so rudderlessit feels like its headed toward an abyss at an ever-increasing pacethat it may truly be important and valuable to salvage as many of the pieces of what we have lived through as possible. The whole twentieth century, and even, through our parents, the nineteenth. Perhaps the more people there are who bear witness to their own experience, the easier it will be to preserve it. Ultimately, it will be possible to piece together a more or less coherent picture of a humane life, of life with a human face, as they like to say nowadays. And perhaps this may have something to offer to the twenty-first century. Im speaking about a composite of voices, of course, in which mine is but a drop, even a fraction of a drop. Keeping this in mind, I can attempt to talk about myself, about what and how I have lived.