This book made available by the Internet Archive.

To Lu K'uan-yu (Charles Luk) to whom the Western world owes much for his lucid renderings of Chinese works containing treasures of Buddhist and Taoist wisdom

Author's Preface

How strangely things come together! Again and again one stumbles upon a word or thought long out of mind only to find it re-echoed perhaps twice or thrice within the space of a few days. Several years ago I toyed with and then discarded the idea of writing a book on mantras. It would not do, I felt, to expose sacred matters to possible derision or lightly set aside the safeguards wherewith mantric knowledge has been guarded from profanation throughout the centuries. In the last few years, however, circumstances have altered. The interest in Eastern wisdom now displayed by thousands of young people in the West is genuine and not wanting in reverence; unlike their elders and forefathers, they do not deride what is mysterious merely because it does not accord with the categories of Western scientific thought. This change of attitude deserves and has received a warm response; nowadays even the most conservative upholders of Eastern traditions are inclined to relax the rigour of ancient safeguards out of compassion for those whose desire for wisdom is sincere but who are unable to journey far from home and sit at the feet of the wise for years on end. No sooner had a series of apparently disconnected incidents caused me to ponder anew the implications of this change than a letter arrived from that outstanding authority and writer on Chinese Buddhism, Lu K'uan-yii (Charles Luk), urging me to set about writing exactly the kind of work I had once had in mind.

My first reaction was cautious. I replied that I felt hesitant on account of the samaya-vov/s which enjoin discretion in regard to all knowledge to which access is attained through tantric initiation; for, though my lama, the Venerable Dodrup Chen, has given me permission to write whatever I deem fitting, I am naturally reluctant to make decisions in such a matter. Then came another letter from Lu K'uan-yii to the same effect as the first. After mulling over his suggestion, I accepted it, but with a self-imposed proviso-that is to say, I decided to confine

X Author's Preface

myself to speaking of mantras which, having already appeared in published works, must certainly be known to (and perhaps misunderstood by) the uninitiated. Thus I hoped to avoid making unwarrantable disclosures and, at the same time, to clear up some probable misconceptions.

Following the general line of approach taken in my earlier books on similar subjects, I have begun at what for me personally was the beginning, by relating more or less chronologically my early encounters with mantric practice. Hence the first two or three chapters have no profundity, though I hope they will be found entertaining. Readers who, hitherto, have equated mantras with magic spells or mumbo-jumbo will find that this was nearly my own position at the start, although faith in the wisdom of my Chinese friends prevented me from closing my mind against what might seem to me nonsense, even if they thought otherwise. I hope I shall succeed in kindling a reverence for mantric arts and belief in their validity just as my own were kindled-step by step.

I should like to stress that I happened upon mantras, rather than came upon them by design. Although my interest in them, once aroused, was perfectly sincere, I made no search for mantric knowledge and what I acquired of it was incidental to my quest for yogas whereby Enlightenment might be achieved, of which mantras sometimes form a part. I have been exceedingly fortunate in meeting men of wisdom and true sanctity both Chinese and Tibetan, many of them well-versed in mantric lore, but I am very far from having achieved a mastery of the subject. That I have dared to write about it is not because I know much, but because many others, lacking my opportunities, may be presumed to know even less. To this day-as the reader will discover towards the end-there are aspects of mantras that remain as mysterious to me as ever. In my own mind, I divide mantras into three categories of which I feel able to speak with some slight authority only on the first:

1 Mantras used in yogic contemplation, which are marvellous but not miraculous.

2 Mantras with effects that are seemingly miraculous.

3 Mantras which, if the claims made for them are vahd, must provisionally be deemed to operate miraculously, at least until the manner of their operation is better understood.

Most of what follows the two or three introductory chapters concerns yogic contemplation. Though this may be thought the least spectacular aspect of mantras, it alone is of ultimate importance.

I am grateful to Lu K'uan-yii for his encouragement; to the Lama Anagarika Govinda for a letter that, taken in conjunction with his published writings, solved several problems for me; to my good friend, Gerald Yorke, for information about the Hindu theory of mantric power as well as about several Western practices analogous to the use of mantras; and to Dom Sylvester Houedard of Prinknash Abbey for the voluminous scholarly notes from which I culled my references to the Jesus Prayer and the Ismu'z Zat of the Sufis.

JOHN BLOFELD,

The House of Wind and Cloud

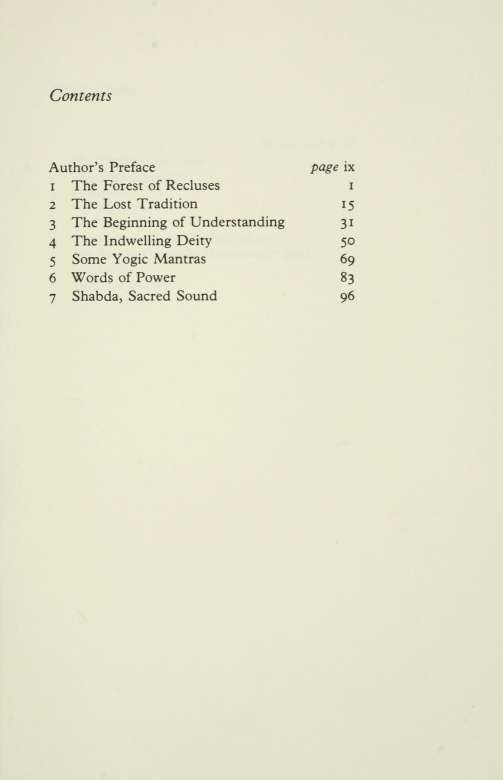

betiveen pages 46-47

1 The Twenty-One Taras

2 Shakyamuni Buddha

3 Yamantaka

4 Avalokiteshvara The White Tara

5 The Precious Guru (in youthful guise) The Precious Guru (in characteristic guise)

6 Manjushri

7 Amitayus Buddha

8 Tara's Mantra

Mantras

Sacred Words of Power

Chapter i

The Forest of Recluses

It was like a dream. Within the wide chamber, though the candle-rays reflected by the chalices and ritual implements assembled upon the altar glittered like silver fire and though the painted mandala of deities rising behind it contained every imaginable hue, the prevailing light was pale gold - the colour of the rice-straw matting that ran from wall to wall, its immaculate surface broken only by the low, square blackwood altar and the rows of bronze-coloured meditation cushions. The cushions were now occupied. But for the motion of their lips and of their breathing, the white-robed figures resembled statues, so profound was the tranquillity conjured up by the deep-toned syllables that, regulated by the drum's majestic rhythm, welled sonorously from their lips.

LOMAKU SICHILIA JIPIKIA NAN SALABA TATA-GEATA NAN. aNG BILAJI BILAJI MAKASA GEYALA SATA SATA SARATE SARATE TALAYI TALAYI BIDAMANI SANHANJIANI TALAMACHI SIDA GRIYA TALANG SOHA!

Presently I came to know that not one of the devotees, though their minds responded to the enchantment without fail, knew the meaning of those syllables whose sound was more inspiring than a solemn paean! The language was not their native Cantonese; nor, despite having been transmitted to their teacher by his Master in Japan, was it Japanese; nor yet medieval Chinese, though the mantra had reached Japan from China a thousand years before; nor was it Sanskrit-but rather Sanskrit modified down the centuries and by a whole series of transitions. Strangely, none of this mattered, for the syllables