Table of Contents

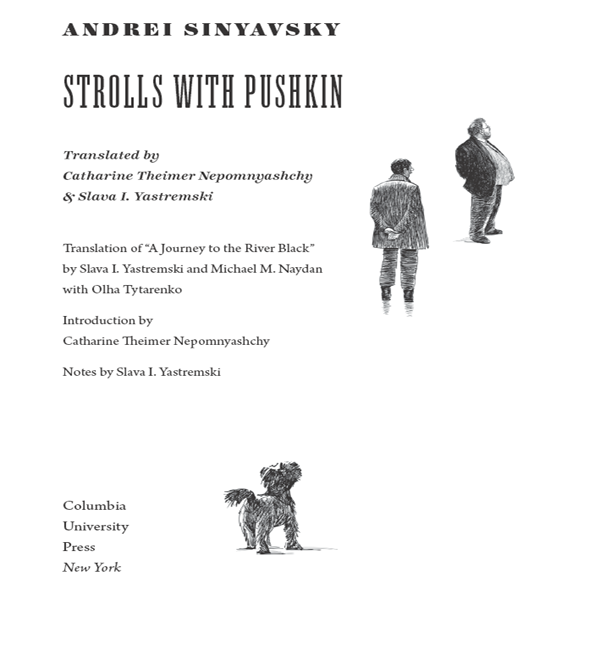

STROLLS WITH PUSHKIN

RUSSIAN LIBRARY

The Russian Library at Columbia University Press publishes an expansive selection of Russian literature in English translation, concentrating on works previously unavailable in English and those ripe for new translations. Works of premodern, modern, and contemporary literature are featured, including recent writing. The series seeks to demonstrate the breadth, surprising variety, and global importance of the Russian literary tradition and includes not only novels but also short stories, plays, poetry, memoirs, creative nonfiction, and works of mixed or fluid genre.

Editorial Board:

Vsevolod Bagno

Dmitry Bak

Rosamund Bartlett

Caryl Emerson

Peter B. Kaufman

Mark Lipovetsky

Oliver Ready

Stephanie Sandler

Between Dog and Wolf by Sasha Sokolov, translated by Alexander Boguslawski

Fourteen Little Red Huts and Other Plays by Andrei Platonov, translated by Robert Chandler, Jesse Irwin, and Susan Larsen

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2017 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54327-9

Published with the support of Read Russia, Inc., and the Institute of Literary Translation, Russia

Cataloging-in-Publication Data available from the Library of Congress

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Roberto de Vicq de Cumptich

Book design: Lisa Hamm

CONTENTS

The vehemence of the reaction to this first Soviet publication of Strolls with Pushkin bears witness to the sensitivity of the topic as well as to its authors gift for challenging the status quo and for performing virtuoso linguistic juggling tricks with the sacred cows of Russian and Soviet culture.

Sinyavskys career began quietly enough. He studied literature at Moscow University during the postwar years and in 1952, the year before Stalins death, he completed the requirements for his candidate degree (roughly equivalent to an American doctorate) and went on to receive an appointment at the prestigious Gorky Institute of World Literature in Moscow, embarking on a promising career as a literary scholar and critic. By the middle of the next decade he was publishing essays and reviews in the Soviet Unions premier literary journal, New World (Novy mir), had co-authored books on early Soviet poetry and on Picasso, and had written a lengthy introduction to a new edition of Pasternaks poetry, establishing his reputation as a rising liberal voice in Soviet cultural life.

In the mid-1950s, however, Sinyavsky literally began leading a double life. Disillusioned with the Soviet systembecause of attempts to recruit him as a KGB informer, the arrest of his father, and the growing divergence between his own tastes in literature and art and those prescribed by the regimehe took the decision to have certain of his writings that could not be published in his homeland smuggled out of the country for publication abroad. The first of these works to appear in the West was a literary manifesto of sorts entitled What Is Socialist Realism, which was published in 1959. The essay is an ironic tour de force in which Sinyavskys narrator poses as a defender of the officially sanctioned Soviet approach to art subsumed under the label socialist realism in order, ultimately, to turn the tradition upside down by subverting it from within. Pointing out the internal inconsistencies in the practice of socialist realism, Sinyavsky concludes by rejecting its subordination of literature to an extraliterary purposefurthering the building of communismand ends the essay with what might be considered his literary credo:

In the given case, I place my hopes on a phantasmagoric art with hypotheses instead of a purpose and grotesque in lieu of realistic descriptions of everyday life. It would correspond more fully to the spirit of our day. Let the exaggerated images of Hoffmann, Dostoevsky, Goya, and the most socialist of them all, Mayakovsky, and of many other realists and nonrealists teach us how to be truthful with the help of absurd fantasy.

In losing our faith, we did not lose our ecstasy at the metamorphoses of God that take place before our eyes, at the monstrous peristalsis of his intestinesthe convolutions of the brain. We dont know where to go, not having understood that there is nothing to be done, we begin to think, to construct conjectures, to suggest. Perhaps we will think up something amazing. But it will no longer be socialist realism.

Following this essay, between 1959 and 1965 three novellas, six short stories, and a brief collection of aphorisms by Sinyavsky appeared in Western publications under the pseudonym Abram Tertz. The fictional works were, in essence, exemplars of the purposeless, phantasmagoric art invoked at the end of What Is Socialist Realism, what Sinyavsky would later come to call (using a term apparently coined by Dostoevsky) fantastic realism. This approach to literature is in turn intimately related conceptually to Sinyavskys pseudonym. Borrowed from Abrashka Tertz, a legendary Jewish bandit whose exploits are celebrated in an Odessa thieves song, the pseudonym identifying the writer as an outlaw has remained Sinyavskys trademark and alter ego long since it outlived its practical usefulness as a blind protecting him from detection by the Soviet authorities.

Despite protests both at home and abroad, Sinyavsky and Daniel were found guilty of anti-Soviet agitation under article 70 of the Soviet penal code and sentenced, respectively, to seven and five years at hard labor. The two writers were transported to different labor camps in the Dubrovlag system near Potma in Mordovia. Daniel served out his sentence there, and was released a year later, in 1971.

Perhaps the greatest irony of Sinyavskys career is that he wrote what would become his most controversial book while imprisoned in Dubrovlag. In a 1990 interview, Sinyavsky explained how he managed to write Strolls with Pushkin and send it out in letters to his wife, Mariya Rozanova, while under constant surveillance by the authorities:

In the same fashion, Sinyavsky completed the first chapter of a book on Gogol while imprisoned, and when he returned home to Moscow after his release he compiled an introspective camp memoir also out of passages from his letters to his wife.

These works represent both a continuation and a further development of Sinyavskys earlier writings. Strolls with Pushkin in effect initiated a new literary genre: fantastic literary scholarship (fantasticheskoe literaturovedenie). Sinyavsky has described this approach to writing about literature as a departure from traditional scholarly writing in which the writer can develop whimsical hypotheses and, in relation to accepted convention, deliberately do things wrong: