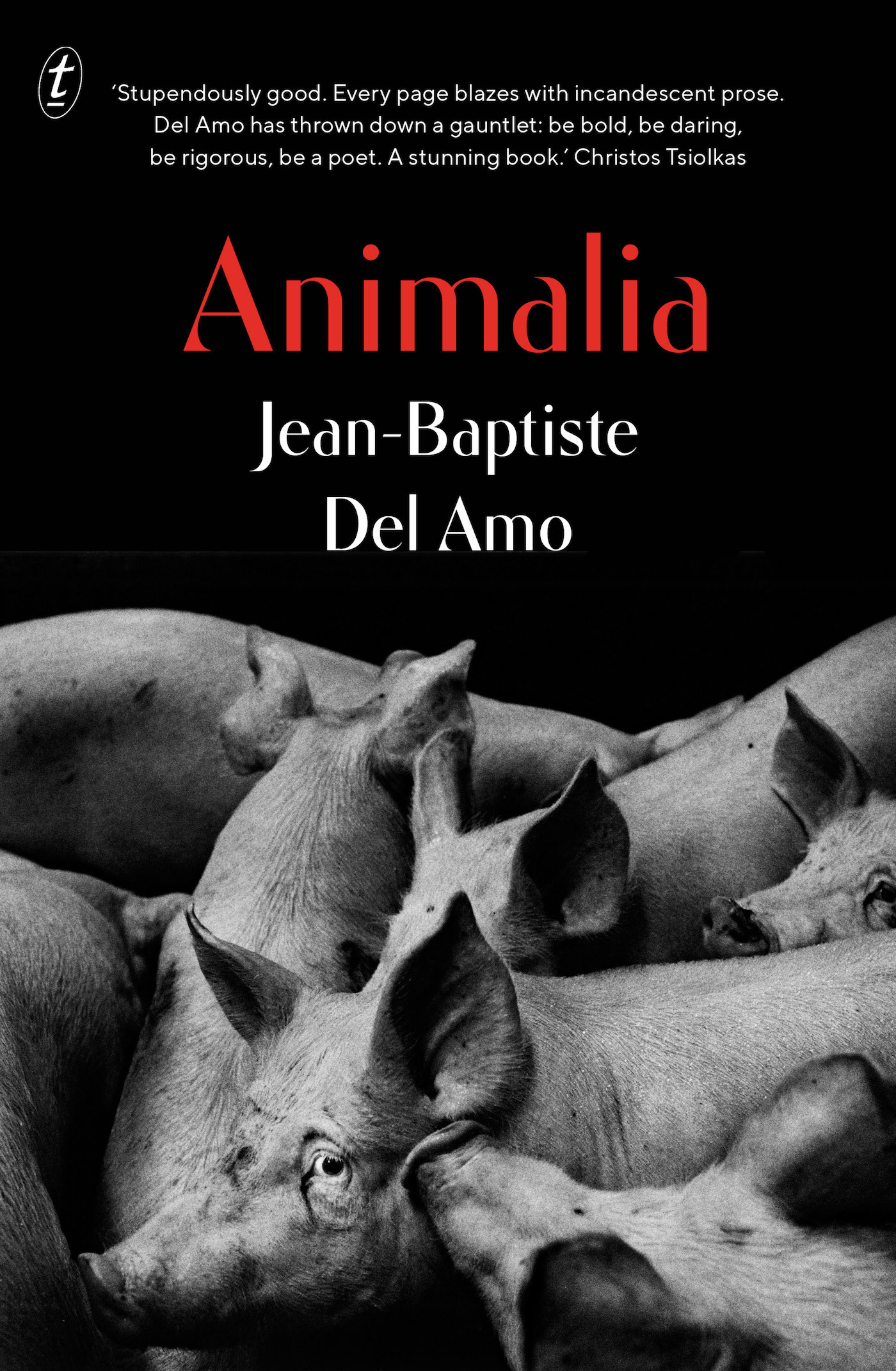

Animalia tells the confronting and compelling story of a peasant family in south-west France as they develop their plot of land into an intensive pig farm. In an environment dominated by animals, five generations endure the cataclysm of two world wars, economic disasters, and the emergence of a brutal industrialism. Only the enchanted realm of childhoodthat of lonore, the matriarch, and Jrome, her grandsonand the innate freedom of the animals offer any respite from the barbarity of humanity. Animalia is a powerful novel about mans desire to conquer nature and the transmission of violence from one generation to the next.

For Sbastien.

For my parents and my sister.

Contents

From the first evening in spring to the last vigils of autumn, he sits on the little worm-eaten hobnailed bench, his body hunched, beneath the window whose jambs frame the night and the stone wall in a small theatre of shadows. Inside, on the solid oak table, an oil lamp sputters and the fire in the hearth projects the bustling shadow of his wife onto walls mottled with saltpetre, shooting it up towards the rafters or breaking it on a corner, and this hesitant, yellow light swells the room and pierces the darkness of the farmyard, leaving the father motionless, silhouetted against a semblance of sunlight. Regardless of the season, he waits for night here, on the wooden bench where he saw his father sit before him, its moss-covered legs buckled by the years now beginning to give way. When he sits on this bench, his knees come a quarter-way up his belly and he has trouble getting to his feet, yet he has never considered replacing it, not if there were nothing left but a board. He believes that things should remain just as he has always known them for as long as possible, as others before him believed they should be, or as custom and wear has made them.

Coming home from the fields, he leans against the door frame and removes his boots, carefully scraping the mud off the soles, then stops on the threshold and inhales the damp air, the breath of the animals, the unpleasant smells of the ragout and the soup that mist the windows, just as he stood as a child, waiting for his mother to beckon him to the table, or for his father to come and hurry him along with a dig in the shoulder. At the nape of his neck, his long, lean body curves and takes a curious angle. A neck so bronzed that even in winter it does not pale, but looks as though it is covered by grimy, cracked leather and seems broken. The first vertebra protrudes from between the shoulderblades like a bony cyst. He takes off his shapeless hat, revealing a pate already bald and freckled by the sun, holds it in his hands for a moment, perhaps trying to remember what he should do next, perhaps waiting for a command from that same mother, long dead now, swallowed and consumed by the earth. Faced with the wifes determined silence, he finally decides to step inside, trailing his own stench and the stench of the animals as far as the box-bed, and pulls the door open. Sitting on the edge of the mattress, or leaning against the carved wood, he unbuttons his rancid shirt between fits of coughing. At days end, what he cannot bear is not the weight of a body which illness has meticulously stripped of fat and muscle, but his own verticality; at any moment it looks as though he might collapse, might fall like a leaf, fluttering in the musty air of the room, right to left, left to right, before settling on the floor or sliding under the bed.

On the fire, in a cast-iron cauldron, the water has finally begun to boil and the genetrix hands lonore the pitcher of cold water. The child takes slow steps, fearful of tilting the jug, which, despite her intense concentration on her hands and forearms, splashes, soaks the rolled-up sleeves of her blouse, as she ceremoniously advances towards the father. She feels a shiver run down her spine beneath the reproachful gaze of the genetrix, who is following close on her heels, threatening to spill the basin of boiling water over her if she does not hurry. Framed in the half-light like a great brig, elbows on his knees, hands hanging limply before him, the father is lost in contemplation of the knotted wood of the wardrobe, or the taper burning on the washstand whose flames struggle against the shadows. The oval of the mirror nailed to the wall offers a distorted, barely visible reflection of the room. Heads poking through an opening cut into the cob wall at waist-height, two cows are chewing the cud. The heat from their stationary bodies and their excreta warm the people. The little scenes played out in the glow of the hearth are reflected in bluish pupils. At the sight of the wife and the child, the father seems to return from some vague daydream to this puny, deep-veined body. Despite himself, he summons the strength to move, stretches his pale back, straightens the torso where grey hairs sprout like rye grass in the furrows of ribs and collarbones. His belly is gaunt, yellow in the candlelight. He extends the arms with their calloused elbows and sometimes gives a faint smile.

The genetrix pours hot water into the bowl set on the washstand. She takes the pitcher from lonore and sets it on the shelf before returning to her kitchen without so much as looking at the father, keen to avoid the sight of this man, bare-chested and raw-boned as the Christ nailed to the wall at the foot of the bed. From high on the cross, He watches over her as she sleeps and appears to her in her late, drowsy prayers, the crucified, funereal effigy of the father sleeping next to her, outlined by a glimmer of moonlight or the guttering stub of a candle whose glow slips through a chink in the door of the box-bed, the man she carefully keeps at arms length, since she cannot bear his sweat, his sharp bones, his ragged breathing. But at times she thinks that, in turning away from this man who married her and made her pregnant, she is betraying her faith and turning away from the Son, and from God Himself. At such times, moved by guilt, she turns to this man, the husband, with a half-look, a faint, grudging gesture of compassion, and gets up to empty the basin of blood-mottled gobs of spittle he hawks up during the night, prepares a poultice of mustard seeds or an infusion of thyme, honey and brandy, which he sips, leaning against the head of the bed, propped up on his pillows, almost moved by this solicitude, taking care not to drink too quickly to signal his gratitude, as though he savours these bitter, ineffective decoctions, while she paces the room. For already the image of the crucified father has faded and with it her guilt, and now she longs to return to bed as soon as possible and lose herself in sleep. She comes and goes, cup or basin in hand, grumbling about his sickly constitution in a voice so low that he takes her words for lamentations, against this chronic infection that has been eating away at his lungs for almost ten years, turning a once hale and hearty man into a haggard, spent creature fit only for a sanatorium; then grumbling about her own misfortune or the cruel fate with which she is forced to contend, she who has already cared for an invalid mother and buried both her parents.

As the father bends over the steaming basin, draws water in his cupped hands and brings it to his face, lonore stands back, attentive to every gesture of these ablutions, performed every evening in precisely the same order, the same rhythm, in the pool of light cast by the lamp. If the genetrix tells her to sit down, she watches out of the corner of her eye, observing the curve of the back, the rosary beads of the vertebrae, the soapy glove passing over the epidermis, the aching muscles, his movements as he slips on a clean shirt. Animated by a fragile grace, his fingers race along the buttons like the tremulous legs of a moth, the deaths-head hawkmoths that eclose from chrysalides in the potato fields. Then he gets up, comes to the table and, when the genetrix in turn sits down, raises his joined hands to his face, his proximal phalanges interlaced, his gaze lost somewhere beyond the ridges of the fingers and their bony knuckles, the grubby fingernails. He says grace in a voice made deeper by his cough and finally they eat, with no sound but their mastication, the grating of cutlery against the bottom of their plates and the buzzing of the flies they no longer shoo from the corners of their lips, the genetrix swallowing hard to choke down the stone lodged against her glottis, the irritation caused by the slavering grunts and grinding of molars that escape the husbands lips.

![St. Jean-Marie Baptiste Vianney - The Little Catechism of the Cure of Ars (with Supplemental Reading: Confession: Its Fruitful Practice) [Illustrated]](/uploads/posts/book/270052/thumbs/st-jean-marie-baptiste-vianney-the-little.jpg)