Dont ask for the true story;

why do you need it?

Its not what I set out with

or what I carry.

What Im sailing with,

a knife, blue fire,

luck, a few good words

that still work, and the tide.

Margaret Atwood, True Stories

CONTENTS

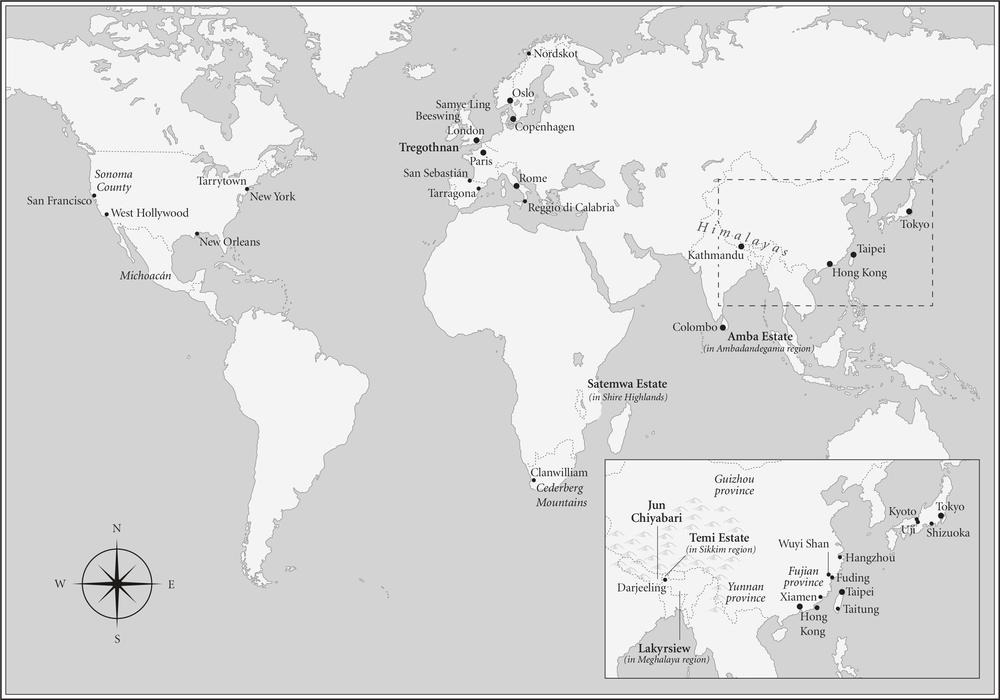

From the Shire Highlands of Malawi, across the foothills of the Himalayas, to hidden gardens of the Wuyi Shan, China, I make my way across the world, hunting for the most extraordinary tea, the leaves of Camellia sinensis. Beyond tea, I seek out rare herbs and flowers, from the pale Marcona almond blossom in Spain to rust-red rooibos of the semi-arid deserts of the South African Cederberg.

I never stop searching. In 2004 I started a small, independent tea business based in London, Rare Tea Company, to share my discoveries. Over the years Ive fallen in love so many times, with so many teas. Im fickle but resolutely loyal. I never un-love. Im not sure how thats done. Once I have given my heart to something, or someone, I cant undo it, so I keep going back, and ever onwards.

When Im not visiting farmers and gardens, my travels take me to my customers. This has led me to some of the best restaurants, past smooth tablecloths and the cool of dining rooms, into the heat and clamour of the kitchens, and to the most fascinating chefs in the world. Tea has introduced me to builders, tattoo artists, teachers, actors, athletes, perfumers, hoteliers, sommeliers, baristas, fishermen, pilots and bartenders. They have become friends and collaborators. My life has become consumed by the finding and blending and sharing of the most delicious things I can find to infuse. Rather aptly, its got me into a fair amount of hot water along the way.

This is the story of my adventures in tea. I hope to seduce you, a little, into a love of loose leaves. Its a highly personal, partisan account rather than an objective treatise on tea in general. Its my story of tea, not the story of tea. I want to tell you about the really good stuff that fuels me, and the places it takes me. There is so much I long to share, you could think of this book as an unburdening of my loves.

It might sound intimidating to venture off completely alone in an unknown country, not speaking a word of the language. But after the initial testing of your newborn giraffe legs, it can be the opposite. Its complete freedom. No one knows you. You know nothing. Nothing is expected of you. Anything could happen.

I have made a life for myself that necessitates embarking on adventures. I cant be sure if this desire catalysed my tea love, but it certainly enables it. The question Im most often asked is how it happened, how I became the Tea Lady. People really do call me that: its what I do and who I am. Ive been pursuing tea for so long now, I have almost forgotten any other life or where the Tea Lady starts and I stop. There is still so much more out there to learn and discover. Ive just begun, though time spools behind me, untidily. Turning a corner in my mind, its often a shock to find how deeply Ive ventured in, the path Ive taken lost in a tangle of leaves.

Before tea I was working for a large multinational corporation, producing financial documentation. I know it sounds fascinating, doesnt it? Shareholder reports, IPO prospectuses and merger agreements arent great topics for conversations over dinner. I had plans to do something else, something I could be proud of, maybe start a tea company, but later. Then my father got cancer. He was sixty-five; he had plans.

I returned home to London from a life in New York and spent my time in the hospital with him, often curled up on the end of his bed. I laid my head down and he stroked my hair. The cancer spread rapidly to his brain. We reversed roles and I sat beside his bed and stroked his hair. It snowed big, fluffy, cinematic flakes over the Royal Marsden Hospital the afternoon he took his last, rasping breath. He died within three months of being diagnosed. I decided not to go back to corporate life, not to delay any longer before plunging into the world of tea.

When I got cancer myself, two years later, just as I was starting Rare Tea Company, it certainly disabused me of the notion that I had time to waste.

I had gleaned a great deal from my years in the corporate world. My job had taken me across the world. I knew how to get things done, and the kind of business I didnt want to be in. I didnt subscribe to cronyism, old boys clubs or the tacit understanding that ethics come second to share value. I wanted to get involved in something that actually meant something to peoples lives. I couldnt just sit passively in the dress circle any longer, looking down at the action on the stage. I set out to work directly with farmers, to travel to their homes, to understand their lives, to support them where I could; to move from grey corridors and windowless rooms full of paper to a vivid life of twisting mountain roads, emerald green gardens and cerulean skies.

Conventional wisdom would have had me buy tea from a broker, stick it in a teabag, get some nice packaging and focus on the PR and marketing. But where would have been the adventure in that? I had fallen for a lovely leaf, not any old bag. Finding the best farms myself, and working on a direct-trade model, pitched me into the complexities of global shipping, without the support of a buying team or a transportation department without anyone, at the start. New routes to market had to be created at both ends, from supplier to customer. Back in 2004, few people in Britain were familiar with loose-leaf tea. My adventures were certainly not founded on the cold hard stare of common sense.

My dreams of tea had been infusing, quietly, for some time. They started in the drawing room of a grand old lady, Diana, in a grey, granite house near the coast of south-west Scotland. I was perhaps five or six when I was old enough to hold a cup and saucer. Tea was poured along with Dianas stories of India and served with great ceremony in fragile bone-china cups. I was surprised and happily terrified to be handed something so precious. I could have bitten right through the thin lip, crushed it up between my small teeth. The tea was Darjeeling the name of a place far, far away that I could taste in sips, right there in Scotland, from the teapot twisted gleaming amber ropes. Scented steam rose from leaves picked on the slopes of hot mountains where monkeys swung, while I looked out at cold hillsides of rough grass and sheep.

We spent all our holidays in Dumfriesshire, where we had family with space for cooped-up London children to run free. The village where my grandparents lived is called Beeswing and compared with the scruffy, terraced streets of south London, it was a fairy tale of a place. We would pile out of the car, its interior opal blue with cigarette smoke after the eight-hour drive, to find a farm, rough-tongued calves with velvet creases behind their ears, and woods thick with wet bracken. We visited the rest of the family in turns for tea. Children were sent to play in the snow or forage for gooseberries, raspberries or wild strawberries and make camps in the head-high bracken. The adults would drink tea until it was a respectable hour to start on the whisky.

Next page