Munshi Premchand - Stories on Caste

Here you can read online Munshi Premchand - Stories on Caste full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 0, publisher: Penguin, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Stories on Caste

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin

- Genre:

- Year:0

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Stories on Caste: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Stories on Caste" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Stories on Caste — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Stories on Caste" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

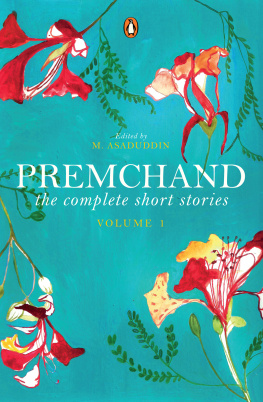

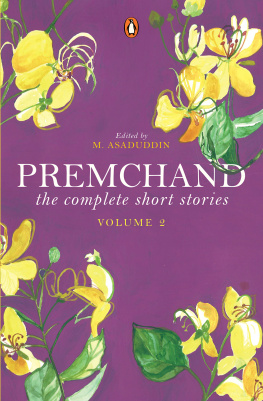

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Shaheen Saba is a PhD student of English at Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi.

Ranjeeta Dutta has completed an MPhil in English from Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi.

Anjum Hasan is the author of the novels The Cosmopolitans, Neti, Neti and Lunatic in My Head. She has also published a collection of stories, Difficult Pleasures, and a book of poems, Street on the Hill. Her books have been nominated for various awards.

Vikas Jain teaches English at Zakir Husain Delhi College (Evening), Delhi University.

Meenakshi F. Paul is a faculty member in the Department of English at Himachal Pradesh University. She is a translator and poet. She has published several articles and books, including a volume on bilingual poetry, Kindling from the Terraced Fields, and a book of translation, Short Stories of Himachal Pradesh.

Moyna Mazumdar has worked with several publishing houses as editor. She also translates from Hindi and Bengali into English.

Premchand is generally regarded as the greatest writer in Urdu and Hindi both in terms of his popularity and the range and depth of his corpus. His enduring appeal cuts across class, caste and social groups. He was not only a creative writer in Urdu and Hindi, but fashioned modern prose in both and influenced several generations of writers. The fact that his works were published in more than two dozen Hindi and Urdu journals simultaneously attest to his extraordinary reach to a wide audience that formed his readership. Many of his readers encountered modern Urdu and Hindi novels and short stories, and indeed any literary form, for the first time through his writings. Premchands unique contribution to the formation of a readershipand, in turn, to shaping the taste of that readershipis yet to be assessed fully. Few or none of his contemporaries in UrduHindi have remained as relevant today as he is in the contexts of the Woman Question (Stree Vimarsh), Dalit Discourse (Dalit Vimarsh), Gandhian Nationalism, HinduMuslim relations and the current debates about the idea of an inclusive India.

Born Dhanpat Rai (18801936) in Lamhi, a few miles from Banaras, Premchands childhood was spent in the countryside. Called Nawab at home, his early schooling was in Urdu and Persian, much in the Kayastha tradition of the time. He also attended the mission school where he studied English along with other subjects. His father was a postal clerk who moved from place to place. When Premchand was only seven his mother died and his father remarried. His relationship with his stepmother was never cordial. He was married at an early age against his wish to a girl who was totally incompatible and he refused to live with her. His second marriage, to a young widow with literary interests, Shivrani, proved to be a happy one. When he was seventeen his father suddenly died and the responsibility of running the family fell on him. He was forced to discontinue his studies and take up the job of a school teacher. However, after his graduation in 1904 he became a sub-deputy inspector of schools, a job which required substantial travel which did not agree with his frail health. In 1921, he gave up government service at the call of Gandhi during the Non-Cooperation movement.

Premchand began writing in 1905 and contributed articles on literary and other subjects in the Urdu journal Zamana. His first short stories were also published in this journal. In fact, Premchand began his career as a short story writer with the publication of Soz-e-Watan (Lament for the Motherland, 1908), written under his pen name, Nawab Rai. The collection drew the attention of the colonial government because of its alleged radical intent. He was summoned, when he was on an inspection tour, to explain his position. This is how Premchand describes the situation in his own words:

... Those days I wrote under the name of Nawab Rai. I already had some information that the intelligence wing of the police was making inquiries to track down the author of the book. I could realize that they have found me out and I had been summoned to defend myself.

The Saheb asked, Have you written this book? I admitted that I had.

The Saheb then asked me to explain the subject matter of each story, and finally burst out in anger, Your stories are full of sedition. Thank God that you are a servant of the British Empire. Had this happened during the Mughal rule both your hands would have been chopped off.

He was asked to burn all the copies of the book, and henceforth, get prior permission from the administration before sending any writing for publication. Petrified, he abided by the demands of the magistrate and submitted all available copies of the book to his office to be destroyed. Premchand realized that writing under the name Nawab Rai was no longer safe and sustainable, and to circumvent the iron hand of colonial censorship he had to assume a new pseudonym, which was Premchand. Thus, both Dhanpat Rai and Nawab Rai were finally buried and Premchand was born, a name by which generations of readers would know him.

Premchand felt a deep affinity with the common man and his natural sympathy was towards the oppressed and deprived sections of society. No writer before him in Urdu or Hindi, and possibly other Indian literatures, had depicted the lives of the underdogs, the untouchables and the marginalized with such depth and empathy. Throughout his life Premchand did not let go of his unsentimental awareness of the grim realities of rural life, of life at the bottom of the economic scale (Amrit Rai: 1982, ix). The oppressors and oppression came in many formsthey may have been priests or zamindars, lawyers or policemen or even doctors, all of whom held the society in their strangle-hold. Rituals pertaining to Hindu marriages and death were so exploitative and oppressive that these events were often robbed of their dignity and joy and spelt the ruin of families.

Premchand began his career by exposing the corruption of the Hindu priestly class in his novel Asraar-e-Muavid (Mysteries of the House of Worship, 190305), and then he continued the tirade in many of his stories. In the story Babajis Feast Babaji ka Bhog he depicts the greed of the Brahmin baba who has no compunction in robbing a poor family of its meagre means, and in Funeral Feast Mritak Bhoj he showed how the predatory and parasitical Brahmins drive another Brahmin woman to destitution and her daughter to suicide. In a series of stories where the central character is Moteram, a Brahmin priest, Premchand exposes with rare courage the rapacity, the hollowness and hypocrisy of the Hindu priestly class, which earned him the ire and venom of a section of high-caste Hindus, even culminating in a law suit for defamation. But he remained undaunted and went on exposing many oppressive customs that were prevalent in society.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Stories on Caste»

Look at similar books to Stories on Caste. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Stories on Caste and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.