EATING MUD CRABS IN KANDAHAR

CALIFORNIA STUDIES IN FOOD AND CULTURE

DARRA GOLDSTEIN, EDITOR

EATING MUD CRABS

~ IN KANDAHAR ~

STORIES OF FOOD DURING WARTIME

BY THE WORLDS LEADING CORRESPONDENTS

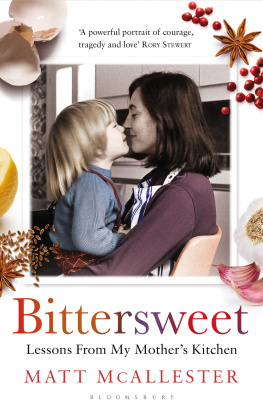

EDITED BY MATT McALLESTER

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu .

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

2011 by Matthew McAllester

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Eating mud crabs in Kandahar : stories of food during wartime by the worlds leading correspondents / edited by Matt McAllester.

p. cm.(California studies in food and culture; 31)

ISBN 978-0-520-26867-8 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Survival and emergency rationsAnecdotes. 2. Food habitsAnecdotes. 3. War correspondentsAnecdotes. 4. Foreign journalistsAnecdotes. 5. WarSocial aspectsAnecdotes. I. McAllester, Matthew, 1969

TX357.E286 2011

394.12dc23

2011017737

Manufactured in the United States of America

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In keeping with a commitment to support environmentally responsible and sustainable printing practices, UC Press has printed this book on Natures Book, a fiber that contains 30% post-consumer waste and meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

FOR HARRY

AND

FOR TIM HETHERINGTON, 19702011

CONTENTS

Matt McAllester

Lee Hockstader

Barbara Demick

Janine di Giovanni

Isabel Hilton

Scott Anderson

Joshua Hammer

Jason Burke

Farnaz Fassihi

Matt Rees

Tim Hetherington

Sam Kiley

Christina Lamb

Rajiv Chandrasekaran

Wendell Steavenson

Jon Lee Anderson

Amy Wilentz

James Meek

Charles M. Sennott

INTRODUCTION

THE NAME OF THE

THIRD CHICKEN

~ KOSOVO ~

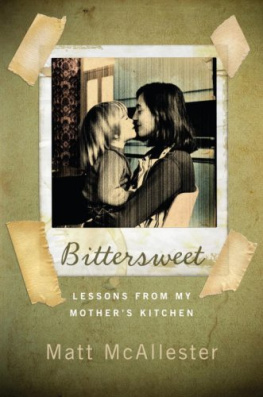

MATT McALLESTER

WHAT DO YOU HAVE TO EAT? I ASKED THE KOSOVAR ALBANIAN woman, at whose wooden hut in the snow-covered Mountains of the Damned I had just arrived, in the company of her son, another reporter, two photographers, and a translator.

Actually, I didnt ask her directly. I asked the other reporter, Philip Sher-well, who spoke German. He then asked the question of the elderly ladys son, Haki, because he too spoke German. He then asked the lady, whose name was Zejnepe, in Albanian. And back, through Haki and Philip and two languages I did not understand, came the answer.

We have some flour and oil for making bread, Zejnepe said.

What else do you have? I asked, looking around at a few other jars and tins on a shelf that lined the walls of the shepherds hut, which was heated with a wood-burning stove. We were warming our frozen bare feet and sodden socks and boots in front of the stove. It was late April 1999 and we had just hiked from the small Yugoslav republic of Montenegro through Serb-controlled territory, at some risk, to visit this old lady who had sworn she would rather be killed than leave Kosovo. Living with her in the tiny hut were five other adult relatives, three elderly, two young. The six of us who had just arrived were exhaustedexcept for Haki, who strolled through the snow and over the mountains as if he was going down to get coffee from the corner store. Philip and I had not known each other long. We worked for different newspapers and were not used to working together. Our exhaustion, coupled with my need to rely on him as a translator, was creating a timbre of irritation in the hut as we continued this crucial interview, which we knew would constitute one of the only firsthand accounts of life inside Serb-controlled Kosovo.

Philip asked Haki, who asked Zejnepe what else they had. Zejnepe told Haki, who told Philip, who told me the answer.

Coffee and sugar, Philip said, and I wrote that down in my notebook.

Can we move on? he added. He had stopped writing in his notebook.

In a minute, I said. Could you ask her if they have any other source of food? They cant just be surviving on bread and coffee.

Philip paused, took a deep breath, and asked Haki, who asked Zejnepe my question.

Every day her nephew, Jeton, goes down the hill to where they keep a cow tethered, and he milks it and brings back the milk, Philip said, and I stared at my notebook and wrote down what he had said and tried not to look at him.

Matt, do you mind if we actually move on to the reason were here and ask about Serbian ethnic cleansing rather than performing an audit of her larder? Philip asked.

Didnt I see some chickens outside? I asked.

Yes, you did, Philip said, without bothering to ask Haki, given that we had unquestionably seen chickens outside the hut pecking in the muddy snow.

Could you ask her how many chickens she has? I said.

Philip put down his notebook.

And would you like me to ask her the name of the third chicken?

No, never mind, I said, realizing that my volunteer translator had just resigned.

Thank you, Philip said, asking a question of his own.

In the years since, Philip and I have often laughed about the name of the third chicken, but I can also still see why the precise number of Zejnepes fowl seemed important to me then. Zejnepe and her relatives looked hungry and drawn. The chickens bought these people time. In the grassy plain that spread out below the snowy mountainsgazing down from the mountains at the plain was like looking at spring from midwinterthe Serbian paramilitary groups usually showed little mercy to remaining Albanians. There was no extra food to be had up here in the mountains. In fact, Jeton and his equally brave father, Emrush, made occasional nighttime excursions down to the plain to get more flour from their abandoned house, which was in a village within view. They had checked the refrigerator, and everything inside had gone off. Philip, his photographer colleague, Julian Simmonds, and I debated going with Jeton on his next journey to get flour, but we decided it was too dangerous. It would have been a nighttime raid to get an ingredient.

War had very rapidly taken a lot from these people: their homes, their freedom of movement, and Zejnepes husband, who had been shot dead by Serbs. And what they were left with was basic shelter, a source of heat, each other, and some larder supplies. Flour, oil, milk, coffee, sugar, eggs, perhaps some chicken meat. Food meant survival, which meant the Serbs had not yet won.

Not all wars are fought over food supplies or other natural resourcesalthough many arebut in all wars food plays a significant role. At some stage in a days fighting, a soldier has to roll behind the wall he is using for shelter to open his army-issue rations. In a day of explaining to her children why they cant go home yet, a refugee mother has to feed them two or three times. In a day of reporting on a conflict, no matter where in the world, a correspondent has to fuel up as well. No matter what role you have in a conflict, you have to step out of it for at least a few minutes every day to have breakfast, lunch, dinneror a piece of bread. Meals put war on hold, even if the guns are still firing outside. And in these moments families regroup, friends tell stories of the day so far and exchange crucial information, and new friends are made; sharing a meal with a stranger is the best way to make you strangers no longer. Amid the awfulness of war, food is a rare, regular source of comfort. And when there is comfort, there is openness. Confidences are shared and jokes cracked. Philip is one of my dearest friends, and many of our bonding moments came over not-very-good meals in places where there was fighting, beginning there in the mountains as we shared breadwith shame but great gratitudethat Zejnepe and her family gave us.