Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

Gerald Duckworth Publishers Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system

now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher,

except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with

a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

Marly

For Katie and Harley

Frontispiece: Marly. Photo Cameron Davidson. Printed by permission of the artist.

: Untitled. Photo Gina Maranto. Printed by permission of the artist.

: Romanian sheepdog puppy. Photo Bruce Stutz. Printed by permission of the artist.

: Study of a Wolf or Dog. 1911. Pen and brown ink drawing by Louis Anquetin. Louvre, Paris. Printed by permission of Runion des Muses Nationaux/Art Resource, NY.

: Gray wolf. Printed by permission of Dave Mech, USGS.

: Feist, common small dog of the American South. Photo Cameron Davidson. Printed by permission of the artist.

: Artemis with hunting dog. Mid-second century Imperial Roman copy of fourth-century BCE Greek original. Museo Chiaramonti, Vatican Museums, Vatican State. Printed by permission of Vanni/Art Resource, NY.

: Tlingit wolf mask, Alaska. British Museum, London. Printed by permission of The Trustees of the British Museum/Art Resource, NY.

: Navajo sheepdogs vie for a piece of cantaloupe thrown by their shepherd, Navajo Reservation. Photo Mark Derr.

: Clio. Photo Gina Maranto. Printed by permission of the artist.

: Lapponian herder, Arctic Circle, Finland. Photo Mark Derr.

: Catahoula leopard dogs working cattle, Louisiana. Photo Cameron Davidson. Printed by permission of the artist.

: Diogenes with dog. Classical. Museo di Vills Albani, Rome, Italy. Printed by permission of Alinari/Art Resource, NY.

: Dogs and Wild Boar. Roman. Museo Archaeologico Nationale, Naples, Italy. Printed by permission of Scala/Art Resource, NY.

: Untitled. Photo Gina Maranto. Printed by permission of the artist.

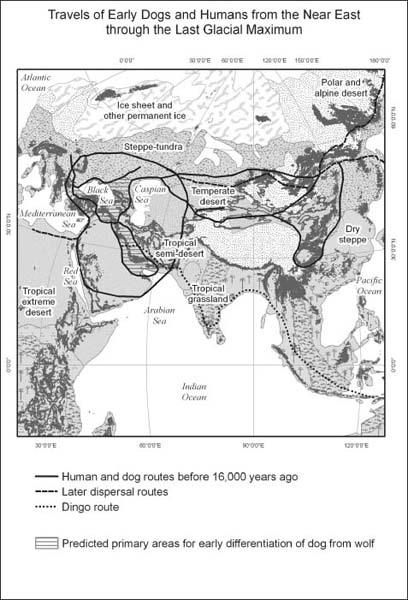

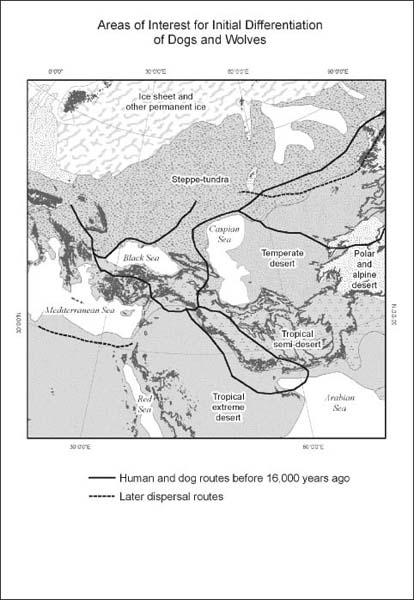

A couple of years ago a young editor at The Overlook Press tracked me through cyberspace to ask if I would consider writing a book about how the wolf became the dog, or in the shorthand of digital communication, Wolf 2 Dog, compressible to W2D. Having studied the question for more than twenty years, I had no illusion that the actual transformation could be so neatly distilled, but I welcomed the chance to examine what was known and suspected against what was possible in the world at the time of the various periods in question. The task is complicated by a difference in scale between geologic time, measured in tens of thousands to billions of years, and biological time, counted in years and decades. Whatever genetic mutations were involved in W2D appeared and were isolated within several generations, and despite continued tinkering in some places by human breeders, those changes have persisted over geological time.

In the past two years, a number of new scientific papers have rocked, if not overturned completelyyetthe prevailing view that the dog was derived from a self-taming group of garbage-dump grazing, juvenilized wolves during the Mesolithic Age, when our forebears, beginning in the Near East or Southeast Asia or both, renounced their big-game hunting migratory ways for exploitation of a more diverse, local food base, including more aquatic life, game of different sizes, and nuts and grains. In fact, about the only certainty left by the fall of 2010 was the identification of the gray wolf as the wild progenitor of the dog, the two being closer genetically than are the races of humans.

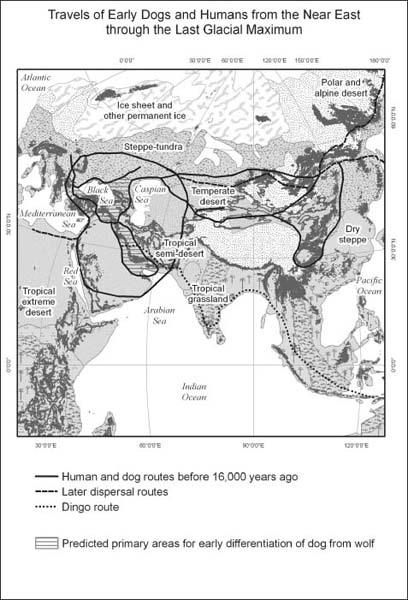

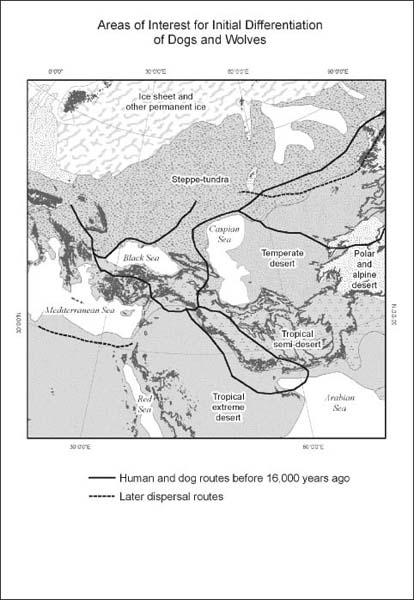

Dog remains dating from around sixteen thousand years ago in the Ukraine, twenty-seven thousand years ago in the Czech Republic, and more than thirty thousand years ago in Belgium were identified. The finds firmly established Europe as the continent with the oldest dogs on record, even though no expert believes that dogs originated there, and more definitively established the dog as a creation of hunting and gathering people on the move.

Increasingly sophisticated genetic analyses have suggested that just a few mutations with large morphological effectsreduced size, dwarfed legs, and brachycephalic, or punched-in, snouts, for exampleaccount for the physiological and, perhaps, the behavioral differences between dog and wolf. For example, a 20-pound animal with bowed, dwarfed legs and a broad, flat nose, like a Pekingese, is going to see and move through the world far differently from a 150-pound mastiff, or a 50-pound Sloughi with its long straight legs capable of speeding close to thirty miles an hour.

Moreover, despite evidence that the little Middle Eastern wolves might serve as foundation stock for the dog, the most sophisticated and thorough genetic survey to date by researchers in the laboratory of Robert K. Wayne, an evolutionary biologist at the University of California at Los Angeles, failed to point to a place where the transformation occurred. Rather, it appears that several types of dog were consolidated from the mixing of Middle Eastern dogwolves with those derived from other wolves.

The question of the dogs origins becomes even more complicated by the association of wolves with hominins, most notably Homo erectus and Homo neanderthalis, who preceded the arrival of our species among the hunters of the Pleistocene. Did they have socialized wolves and even dogwolves? Without firm evidence of the hominins direct association with wolves, I suggest that even if they did, their animals do not figure in the evolution of the dog in human society. Nonetheless, the hominins cannot be ignored, since they were full members of the Guild of Carnivores, the big predators who fed on the migrating herds of reindeer and horse. To keep them in proper perspective relative to their other guild members, I often refer to them as furless bipeds, because they lacked their own fur.