THE FIRST DOMESTICATION

Copyright 2017 by Raymond Pierotti and Brandy R. Fogg.

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Scala and Scala Sans type by IDS Infotech, Ltd., Chandigarh, India. Printed in the United States of America.

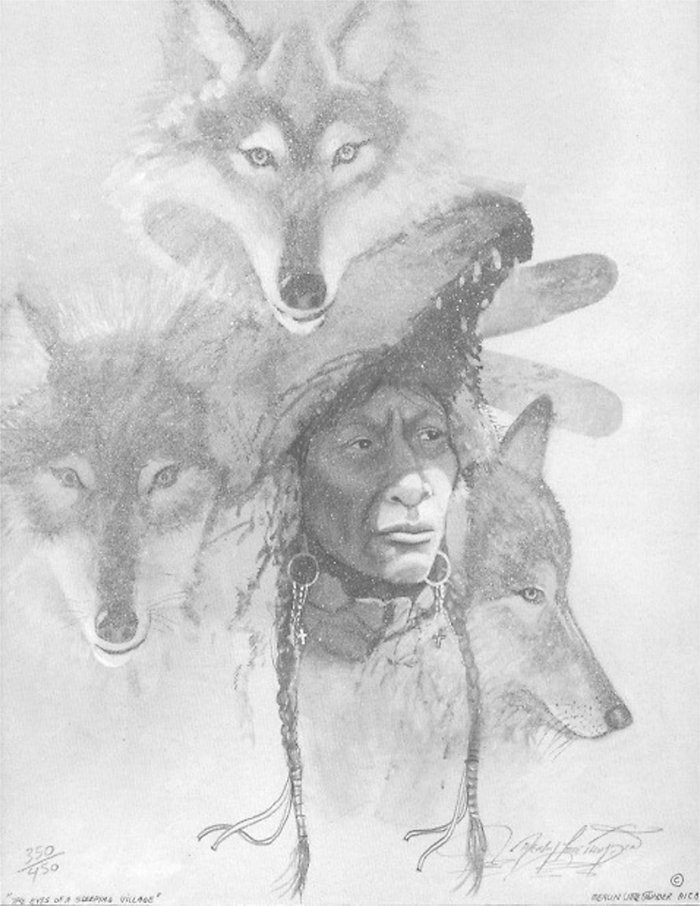

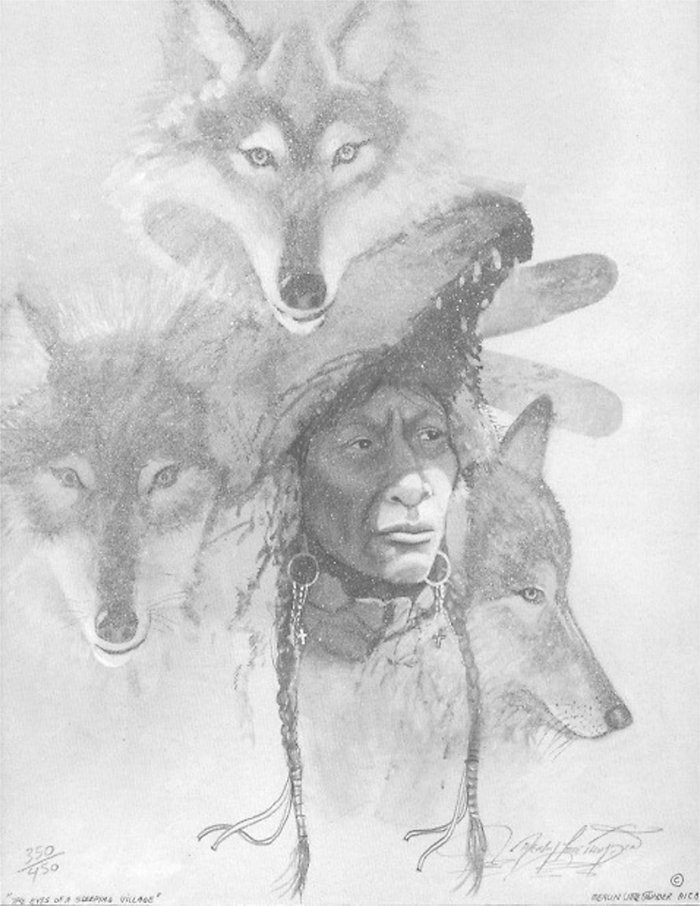

Frontispiece: Eyes of a Sleeping Village, by Cheyenne artist Merlin Little Thunder (Courtesy of the artist)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017936094

ISBN 978-0-300-22616-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Cynthia Annett, who always provides wise guidance, and to the memories of Tabananika, Nimma, and Peter: companions, friends, and teachers

CONTENTS

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

When the first modern humans moved out of Africa and into the vast continent of Asia, wolves were the most widely distributed large mammal in the world, ranging across the entire Northern Hemisphere. To achieve this, they had to have been highly adaptable to conditions ranging from the subtropics of southern Asia to the Arctic regions of Asia and North America. There was no obvious reason for wolves to ally themselves with bipedal primatesand, in fact, many believe that they did not choose this association with early humans; it was forced upon them.

In our efforts to produce a significant new contribution to a crowded field, we looked to a source that has been largely ignored in investigations of the evolution of humans and their ecological relationships with other species: the solid information contained within accounts from Indigenous peoples around the world. When we began work on this manuscript, Brandy Fogg was a masters student in the Indigenous Nations Studies Program at the University of Kansas, and Raymond Pierotti was a faculty member with an appointment split between that program and the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at KU. Our goal was to examine the relationship that nondomestic wolves had with Indigenous peoples by studying how the Indigenous peoples themselves described and characterized that relationship.

Looking at the human/wolf relationship from this perspective is important because, with one possible exception (Rose 2000, 2011; see below), every other book that has examined the history of the domestication of wolves has been written primarily or exclusively from a contemporary Western (European or Euro-American) point of view. Many of these books are excellent and insightful, but authors from the Western tradition almost always assume that early relationships between humans and wolves involved competition, violence, and hostile rivalry rather than cooperation and compatibility. This perspective rests on either of two major assumptions: (1) that humans stole wolf puppies from dens, or (2) that some wolves, unable to hunt for themselves, took scraps from human refuse dumps and in the process evolved on their own into dogs. The overriding theme in both assumptions is that these wolves became dependent on humans, who controlled the relationship. Finally, it is assumed to have taken thousands of years of selective breeding to turn wolves into the domestic dogs we see today.

In marked contrast to this Western perspective are accounts from Indigenous peoples, who invariably describe congenial interactions between wolves and humans involving the freedom of wolves to come and go from human encampments as they chose. These accounts provide evidence that such relationships lasted well into recent times, ending only when the peoples themselves were forced off their lands and out of their traditional ways of life as the wolves simultaneously came under genocidal attack through the pressures of colonialism. In many cases, Indigenous peoples explicitly describe how their companions the wolves suffered similar or worse levels of persecution by invading Europeans. Indigenous narratives do not describe stealing puppies but playing with puppies. In a few instances, they report rescuing puppies from dens when the parents could not provide for their entire litters. The humans raised these puppies, some women actually nursing the puppies from their own breasts, and when the pups reached sexual maturity, they would leave the humans but return periodically to hunt with them or to cooperate in making it through a hard winter. Basically, both wolves and Indigenous peoples knew that their lives were longer and more secure when they shared them together.

A story recently told by a Native American scholar illustrates this type of relationship, although it describes a domesticated animal rather than a wild one:

One ... traveler that crossed my path was a dog. Where he came from we never knew, nor ... where he went after his sojourn with us.... One evening there was a loud commotion.... My grandfather and I found the reason: a skinny, gray dog ... stood his ground ... hardly annoyed by the snarling feints [of our dogs].... The commotion ceased and my grandfather tossed him a scrap of meat. The greyhound delicately picked it up and trotted off.... I thought he was gone for good.... But I was wrong. The next morning he was sitting ... waiting.... I chose to ignore him. My grandmother ... fed him. I guessed that he decided to stay around for those scraps, until I saw him catch a rabbit. My grandfather and I ... noticed ... the greyhound ... following us ... when a jackrabbit exploded from a low thicket and bounded across the prairie. The greyhound flashed past.... The rabbit accelerated, moving faster than I had ever seen any living thing move. It seemed to glide above the grass. Foolish dog, I thought ... you will not catch that rabbit.... As the rabbit hit top speed, the dog seemed to angle to the left and ... was a grey blur through the grass.... Jackrabbits ... have a peculiar habit of making a wide circle when pursued. No four legged hunter on the prairie can match their straightaway speed.... They eventually make a wide turn and end up near ... their den or burrow, having easily outrun any pursuit.... Off in the distance, perhaps a hundred yards, two gray forms collided, then came a faint squeal, then silence.... The greyhound ... hit the jackrabbit in mid-stride, closing on him at an angle ... [and] caught himself a sumptuous meal.... I couldnt believe the dog had outsmarted the jackrabbit.... He shared his food with our dogs, after dragging the rabbits carcass across the prairie.... He stayed with us over the winter until early spring. Then, just as suddenly as he had appeared, he took his leave. (Marshall 2005, 4144)

The author of this account, Lakota scholar Joseph Marshall III, has been one of our inspirations. His book On Behalf of the Wolf and the First Peoples (1995) provided us with a basic framework for some of our arguments as well as confirmation that we were on the right track.

The approach we take was inspired by the work of the insightful German ethologist Wolfgang Schleidt, who in 1998 posed the question Is humaneness canine? Schleidt argued that much of the behavior of modern humans can be traced to their relationship with wolves and dogs. Schleidt followed this up with a more developed argument that posited an alternative view of dog domestication, suggesting that the scientific name for modern humans might be better

Next page