The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

For my mother and father

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to the team at Faber and Faber: Julian Loose for being both an inspiring and a patient editor, and, above all, for allowing me a second opportunity, and to Angus Cargill, Kate Ward and Ron Costley; Professor Philip Horne for keeping me at it and seeing me through; Professor Karl Miller for his support, for teaching me a thing or two, and for giving me the benefit of his scholarship and critical skills; and the much missed Professors Roy Porter and Tony Tanner for telling me it was good; Julia Jkel for her all-too-necessary patience with the German passages; Hilary Cook and John Collingwood; Adrian Garvey; Annie Cooper; Dr Cheryce Kramer for giving me the invaluable help of believing in me; Dr Chris Hamilton for his encouragement, and for taking things seriously; Dr Lorna Gibb for her knowledge of both linguistics and Burt Bacharach; Dr Emma Widdis for being a brilliant amateur detective; Sara Dane, who said exactly the right thing; Olivia Goodwin for helping me to write, and especially for providing the kindness, support and wisdom that made all the difference; Jane and Phil Cole for putting a roof over my head; and my mother and father, without whose love and immense generosity this book would never have been completed.

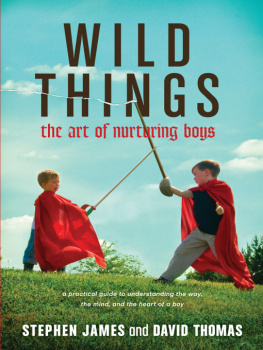

Other people also read this book before it was a book, and offered excellent advice: Dr Stephen James; Dr Christine Gttler; the incomparable Lee Sands; Catherine McLoughlin; Miranda Davies; Debbie Humphry; Dr Anne Button; and Sarah Lusznat, who saved me, as ever, from making a terrible mistake.

Thanks to Linda Garmon and Jay Shurley, who told me fascinating things about Genie and helped enormously with picture research; Seamus Heaney; Simon Elliott at the Department of Special Collections at UCLA; Colonel Richard Brook and the Board of Trustees at the Chevening Estate.

Thanks to Helen Hayward and John Armstrong for their generosity. And thanks to Cris Popa, Thalia Thompson and Vivienne Hammond for never asking me if Id finished it yet, and to Richard Allen and Jason Whiston for never giving up on asking me the same question.

Thanks to Debbie Brown, for taking me to Ireland and giving me a clue to the whole thing.

I would also like to thank the following institutions for financial support given during the inordinately long time I spent writing this book: The British Academy; the Department of English at University College, London; the Irwin Fund of the University of London; Harvard University; The Charles Lamb Society; The Fabian Society. This book wouldnt have been finished without the support of the five people who generously kept me in work: Professors John Sutherland, David Trotter, Michael Wood, and Caroline Dakers, and my unofficial agent, Roger Sabin.

I want to acknowledge my indebtedness to four people I have never met, but whose books on the same subject as my own have provided me with patterns of excellence in their research and writing: Harlan Lane, author of The Wild Boy Of Aveyron (also for some very useful advice on picture research); Jeffrey Masson, author of Wild Child: The Unsolved Mystery of Kaspar Hauser; Charles Maclean, author of The Wolf Children; and Russ Rymer, author of Genie, A Scientific Tragedy.

I am very grateful to all those people whove expressed enthusiasm for the book. Thanks to David Bryer for providing Hauserian information. And special thanks to the brilliant Anna Pallai, Kate Burton, Tara Hiatt and the indefatigable Camilla Smallwood at Faber.

Finally, I thank my teachers: John Smithies; David Akers; Professor Henry Woudhuysen; Professor Stanley Cavell; and Brother Edwin.

Foreword

These are tales of pursuit. The pursuers are various: the young French surgeon flushed with the possibilities of a great enterprise; the wearied, sardonic Scottish doctor; the village priest willing to believe; the eccentric judge; the gentleman of leisure; the errant aristocrat. Yet the object of their pursuit is constant. All of them seek the truth, one that is embodied in another human being; and, for each one, that truth is something that can only be found in the exceptional fate of this boy, of this girl. That is the end of their quest: to fix for a moment the fleeting truth glimpsed within the life, the eyes, the soul, of the wild child.

Wild child or feral child: the phrase covers a multitude of stories. Mostly it describes children brought up by animals; but over the last few centuries these words have been applied to children who have grown up alone in the wilderness, lost in the woods and forests. More strangely the same phrases are also used for those few children who have lived through another, perhaps crueller kind of loneliness, locked for long years in solitary confinement in single rooms. What unites all these stories is the image of a human life developing in complete isolation, cut off from all human contact.

Such stories have afforded generations of scholars, writers and philosophers insights into the very essence of humanity. These children raise the deepest and most insoluble of questions: what is human nature? Does such a thing even exist? How do we differ from other animals? Where does our identity come from? And the inevitable silence of these children provokes a further mystery: what part does language play in creating our humanity?

Behind all these questions lies one final source of uncertainty and intrigue: what makes us human? Somehow these stories of abandoned children, suffering children, of savage girls and wild boys, always bring us back to this implacable and insoluble source of fascination. It is a fascination that this book will set out to explore, doing so through the fragmented and disrupted biographies of children whose histories are partially lost.

Come on, poor babe

Some powerful spirit instruct the kites and ravens

To be thy nurses! Wolves and bears, they say,

Casting their savageness aside, have done

Like offices of pity.

William Shakespeare, from The Winters Tale

CHAPTER ONE

The Child Of Nature

Men saye that we have bene begotten miraculously, fostered and geven sucke more straungely, and in our tendre yeres were fedd by birdes and wilde beasts, to whom we were cast out as a praye. For a wolfe gave us sucke with her teates Nowe amongst the warders, there was by chaunce one that was the man to whom the children were committed to be cast awaye, and was present when they were left on the bancke of the river to the mercie of fortune.

From Norths translation of Plutarchs Life of Romulus

In the years since the fall of communism, as the social fabric of Russia was rent and fell apart, street kids became a common sight in Moscow or St Petersburg. Like the homeless in London, they were both ever present and subtly invisible a backdrop to city life; an irritating intrusion into the process of simply getting on with things. But one of these Moscow street kids was different. He was actually to find the visibility that had so long been denied to him.

In 1996, Ivan Mishukov left home. He was four years old. Ivans mother could not cope with him or with her alcoholic boyfriend, so the little boy decided that life on the streets was better than the chaos of their apartment. Just as Moscow has its homeless, so it has its wild dogs, an inevitable consequence of the inability to create facilities for the citys many strays. Dogs are abandoned with mournful regularity, and quickly turn feral, rummaging through bins for scraps, running around the streets in packs in order to survive. Out on the streets, Ivan began to beg, but gave a portion of the food he cadged each time to one particular pack of dogs. The dogs grew to trust him; befriended him; and, finally, took him on as their pack leader.