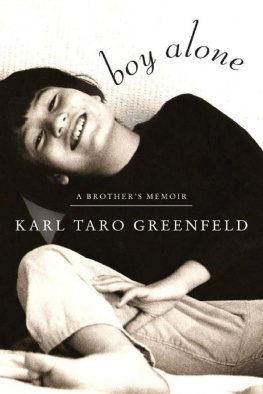

SPEED

TRIBES

DAYS AND

NIGHTS WITH

JAPANS NEXT

GENERATION

KARL TARO GREENFELD

A Division of HarperCollinsPublishers

FOR FOUMI AND JOSH

CONTENTS

I was born in Kobe, Japan, of an American-Jewish father and a Japanese mother. I grew up in Los Angeles and went to college in New York. In 1988, when I was twenty-three, I returned to Japan and landed a job covering trade agreements and visiting dignitaries for the English-language spin-off of Tokyos leading daily newspaper. I wound up staying in Tokyo for five years, moving from reporter to managing editor of a monthly city magazine and then finally free-lance writer.This was the era of the bubble economy.Tokyo from 1985 to 1991 saw what some believe was the greatest concentration of wealth in the history of the world. Between 1985 and 1989, Japans GNP grew 30 percent; the value of Japans assets increased 80 percent. The real estate value of Tokyo, the received wisdom had it, was greater than the real estate value of the entire United States plus the asset value of every company listed on the New York Stock Exchange. The value of the Imperial Palace alone, about ten acres in downtown Tokyo, was greater than that of the entire state of California. Spurred by the overcentralizing of government bureaucracies and buildings in Tokyo and the citys strict tenants rights laws, prices in good neighborhoods doubled every three yearsevery two years in the prime Marunouchi or Akasaka neighborhoods, if you were lucky enough to find someone willing to sell. A three-bedroom house on a twentieth of an acre an hours ride from Tokyo, which sold for $100,000 in 1979, sold for $1.5 million in 1989. A one-bedroom condominium in the tony Hiroo section of town with a view, parking space, and all mod cons: $2.5 million.As real estate soared, investors took out cheap loans, using the endlessly escalating values of their properties as collateral, and bought into the rising stock market. Capital thus generated blew back into the real estate market. The baburu (bubble) inflated. With asset appreciation spreading like crabs in a whorehouse, anyone who went into the bubble days with some capital and an IQ over six was flush by the late eighties. Only idiots and foreigners didnt get rich during the bubble, an equity warrants salesman for Japans largest securities house once confided to me.Designer boutiques flourished, nouvelle cuisine restaurants opened daily, jewelry and gold vendors couldnt keep up with demand. There was money everywhere and it had to be spent. Between 1985 and 1990, about $700 billion flowed abroad in exchange for Louis Vuitton steamer trunks and Rolex Oyster Perpetual watches bought in Paris or Genevaor for flagship buildings and movie studios purchased in New York or Los Angeles.You saw the money in the streets of Tokyo, glimpsed it in the rows of chauffeur-driven, double-parked black Lexuses, Benzes, BMWs, and Bentleys idling outside of posh Ginza or Roppongi watering holes. Felt it in the crush of consumers jockeying for position at the Tiffany counter in the Mitsukoshi department store. Heard about it from bar hostesses who described their customers taking them out for thousand-dollar, seven-course dinners. I remember watching a videotape of an NFL play-off game a friend had sent me from the United States. At one point there was a slick commercial in which a silver, gull-wing Mercedes sports car from the fifties rotated on a pedestal while an auctioneer took bids, photographers snapped pictures, and potential buyers oohed and aahed at the fine piece of machinery on display. The gist of the commercial was that Mercedes-Benz made very exquisite, very expensive cars, which eventually, if you kept them for forty years, became objets dart that were highly sought after by collectors. In the lot across the street from my cramped Tokyo apartment, three of those gull-winged collectors items were parked.In December 1989, the Tokyo Stock Exchanges Nikkei Index peaked at 38,915.87. In less than two and a half years it would be down 60 percent, with trading volume off close to 80 percent. Real estate plummeted as much as 50 percent. If you could find a bidder. In other words, everything in the country was suddenly worth half of what it had been two years earlier. And by 1993 the market hadnt yet recovered. Scandals also frightened investors away. Nomura Securities, Japans largest brokerage house, was caught compensating preferred clients for stock losses and engaging in other chicanery.In addition, the highly publicized Japanese purchases in America, such as Mitsubishi Estates acquisition of Rockefeller Center, in which it overpaid by as much as $400 million, were certified disasters. The thing about the Rockefeller Center situation is that its one case out of dozens. There are too many to mention, a Mitsubishi Estate executive told me.The bubble had burst.In 1991 I was dating a twenty-year-old English woman. Nina had short, cropped, blond hair and the pale, blemish-free skin Japanese men were supposed to be very fond of. For five hours a night, six nights a week she poured drinks for, batted eyelashes at, and made small talk with Japanese businessmen at a popular Roppongi hostess bar. Occasionally, she would have dinner with a customer. For her services as a hostess she was paid handsomely, 7,000 ($64) an hour, plus whatever she could coax in tips from her clients, usually about $200 a night. Nina made over $10,000 a month. I saw her late at night, at the earliest around one, usually later: two, three, or four in the morning. Sometimes she would keep me waiting until dawn at El Macombo or Deja Vu or Gas Panic or any of the other dingy bars where hostesses went after work. I knew this going into the relationship: if our affair was to work, no jealousy was allowed.But then I saw the new four-carat diamond pendant dangling from her neck sparkling brightly in the streetlights white light. It was two A.M . and I was standing just inside the saloon doors of Sunset Strip, a bar on Roppongi Dori between Nishi Azabu and Roppongi Crossing in central Tokyo. We had arranged to meet there after she finished her nights work. As Nina climbed from the tan leather seats of a dark blue Bentley convertible, the pompadoured owner, in a yellow-and-green tropical print shirt, and I exchanged glances, his laced with contempt and mine with jealousy. The smirking owner was three years younger than his twenty-two-year-old, black-suited driver. The driver was three years younger than me.When I saw that four-karat diamondbig and hard enough to cut glass, flesh, soul, or whatever you put in its pathI felt a pang of jealousy and anger and resentment first toward the smug, Bentley-owning, real estate-dealing, expense account-wielding Japanese guy who had given it to her and then toward Nina herself. When she entered the bar I told her I wanted to leave and she shrugged and said, Fine, perhaps sensing my bad mood but unaware that I was about to break the unspoken no-jealousy-allowed rule.Six-lane Roppongi Dori stank of fruity and fishy garbage that had been cooking and fermenting in the tropical July heat. The two-tiered elevated expressway that divides central Tokyo loomed overhead, the whir and rush of traffic audible from where we stood seventy feet below. The surface streets were empty save the occasional taxi cruising for a fare.Nina walked ahead of me. She was wearing a tight, short black dress made from some kind of cotton, probably with a little polyester or Lycra spandex woven in for elasticity. Moschino? Alaia? Gaultier? She was in, as usual, flat shoes; she didnt want to appear taller than her Japanese customers. She wore a Cartier tank watch with a black lizard band (another gift from a wealthy customer) and carried a small black purse barely capacious enough for a lipstick.We passed a shuttered vegetable shop, a small business hotel, and a convenience store before she turned to me and said, in her Cockney accent, And what the fucks wrong with you?And in the nanosecond before we were going to have it outfight? break up? slap each other? go back to my place and make love? or just realize we didnt like each other very mucha loud, throaty chorus of engine growls, like chain saws through megaphones, came up behind me. A motorcycle gang of twenty-five Japanese kids with tightly curled, permed hair and mirrored sunglasses, dressed in the green aviator suits of kamikaze pilots, roared past. From their bikes flew Rising Sun flags.The gang rode slow and loud, taking up all three westbound lanes of Roppongi Dori. Their small-engine bikes had been modified beyond recognition with chrome handlebars, decorative mirrors, fiberglass packing, and triple-header tail pipes that increased exhaust noise to ear-splitting volume. They looked at Nina, in her short, sexy skirt, and me and revved their motors, waved their flags, hit their four-trumpet horns, swerved from side to side and made sparks by striking the pavement with their kickstands. A few of the bikers cat-called or gave us the finger. Most of them just stared impassively and gunned their fantastically loud machines. One, a well-muscled youth with impressive tattoos of intertwining dragons and snakes, rode shirtless, and when he looked at me he grinned. A gold tooth flashed.They were bosozoku out for a Saturday night run. On the backs of their kamikaze uniforms were ancient Chinese characters of a style I had never seen before.At that moment, with the cycles roaring and the hostess beside me, I realized that the Japan I had been writing about as a reporter and magazine editor had nothing to do with the Japan I was living, breathing, smelling, and seeing firsthand. In the flurry of having to bat out stories about microchip dumping, trade disputes, or twenty-dollar cups of coffee, I had overlooked the gritty, sexy, real Japan: the dazzling variety of new youth subcultures and rich pop cultures emerging as a result of the bubble economy prosperity. Speed tribes, a literal translation of bosozoku , is the term I have come to use in referring to all these new subcultures. They are not the Japan that a foreign journalist riding an expense account uncovers when interviewing a deputy minister of finance. Nor are they the quaint picture-postcard Japan of tea ceremonies, sumo wrestlers, rock gardens, and Kabuki. The twenty-five million Japanese between the ages of fifteen and thirty bear little resemblance to the twelve-hour-day salarymen or kimono-clad geisha familiar to westerners; they are a far cry from their generational predecessors, the shinjinrui , the Japanese baby-boomers. The speed tribes, the children of the industrialists, executives, and laborers who built Japan, Inc., are as accustomed to hamburgers as onigiri (rice balls), to Guns N Roses as ikebana (flower arranging), and are often more adept at folding a bindle of cocaine or heroin than creasing an origami crane.Standing there, with the pretty blond hostess frowning at me and the motorcycle gang giving me the finger, I decided my Japan would be life in the bars, at the nightclubs, and on the streets. I had never read about this Japan in Time, Fortune , or the Wall Street Journal. I would hang out with these kids and write their stories.Nina and I didnt break up that night. Our particular bubble burst a few weeks later, and when we split up the reason wasnt expensive gifts from rich Japanese guys or my jealousy or the debilitating late hours we kept. What finally did us in was an argument about money. I borrowed fifty thousand yen, about four hundred dollars at the time, and was a little slow paying her back. That annoyed her so she dumped me.And began dating the guy in the Bentley.

Next page