Time Crime

by

Henry Beam Piper

1955

All Your Books Are Belong To Us !

http://c3jemx2ube5v5zpg.onion

Time Crime

Copyright 1955 Henry Beam Piper

Produced by Greg Weeks, Sankar Viswanathan, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

This etext was produced from Astounding Science Fiction Magazine February and March 1955. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the copyright on this publication was renewed.

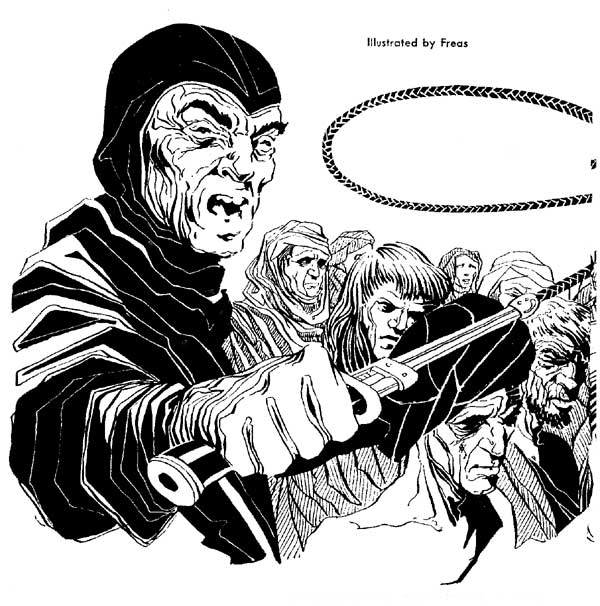

Illustrated by Freas

The Paratime Police had a real headache this time!

Tracing one man in a population of millions is easy compared to finding one gang hiding out on one of billions of probability lines!

Contents

Part 1

Kiro Soran, the guard captain, stood in the shadow of the veranda roof, his white cloak thrown back to display the scarlet lining. He rubbed his palm reflectively on the checkered butt of his revolver and watched the four men at the table.

And ten tens are a hundred, one of the clerks in blue jackets said, adding another stack to the pile of gold coins.

Nineteen hundreds, one of the pair in dirty striped robes agreed, taking a stone from the box in front of him and throwing it away. Only one stone remained. One more hundred to pay.

One of the blue-jacketed plantation clerks made a tally mark; his companion counted out coins, ten and ten and ten.

Dosu Golan, the plantation manager, tapped impatiently on his polished boot leg with a thin riding whip.

I don't like this, he said, in another and entirely different language. I know, chattel slavery's an established custom on this sector, and we have to conform to local usages, but it sickens me to have to haggle with these swine over the price of human beings. On the Zarkantha Sector, we used nothing but free wage-labor.

Migratory workers, the guard captain said. Humanitarian considerations aside, I can think of a lot better ways of meeting the labor problem on a fruit plantation than by buying slaves you need for three months a year and have to feed and quarter and clothe and doctor the whole twelve.

Twenty hundreds of obus, the clerk who had been counting the money said. That is the payment, is it not, Coru-hin-Irigod?

That is the payment, the slave dealer replied.

The clerk swept up the remaining coins, and his companion took them over and put them in an iron-bound chest, snapping the padlock. The two guards who had been loitering at one side slung their rifles and picked up the chest, carrying it into the plantation house. The slave dealer and his companion arose, putting their money into a leather bag; Coru-hin-Irigod turned and bowed to the two men in white cloaks.

The slaves are yours, noble lords, he said.

Across the plantation yard, six more men in striped robes, with carbines slung across their backs, approached; with them came another man in a hooded white cloak, and two guards in blue jackets and red caps, with bayoneted rifles. The man in white and his armed attendants came toward the house; the six Calera slavers continued across the yard to where their horses were picketed.

If I do not offend the noble lords, then, Coru-hin-Irigod said, I beg their sufferance to depart. I and my men have far to ride if we would reach Careba by nightfall. The Lord, the Great Lord, the Lord God Safar watch between us until we meet again.

Urado Alatana, the labor foreman, came up onto the porch as the two slavers went down.

Have a good look at them, Radd? the guard captain asked.

You think I'm crazy enough to let those bandits out of here with two thousand obus forty thousand Paratemporal Exchange Units of the Company's money without knowing what we're getting? the other parried. They're all right nice, clean, healthy-looking lot. I did everything but take them apart and inspect the pieces while they were being unshackled at the stockade. I'd like to know where this Coru-hin-Whatshisname got them, though. They're not local stuff. Lot darker, and they're jabbering among themselves in some lingo I never heard before. A few are wearing some rags of clothing, and they have odd-looking sandals. I noticed that most of them showed marks of recent whipping. That may mean they're troublesome, or it may just mean that these Caleras are a lot of sadistic brutes.

Poor devils! The man called Dosu Golan was evidently hoping that he'd never catch himself talking about fellow humans like that. The guard captain turned to him.

Coming to have a look at them, Doth? he asked.

You go, Kirv; I'll see them later.

Still not able to look the Company's property in the face? the captain asked gently. You'll not get used to it any sooner than now.

I suppose you're right. For a moment Dosu Golan watched Coru-hin-Irigod and his followers canter out of the yard and break into a gallop on the road beyond. Then he tucked his whip under his arm. All right, then. Let's go see them.

The labor foreman went into the house; the manager and the guard captain went down the steps and set out across the yard. A big slat-sided wagon, drawn by four horses, driven by an old slave in a blue smock and a thing like a sunbonnet, rumbled past, loaded with newly-picked oranges. Blue woodsmoke was beginning to rise from the stoves at the open kitchen and a couple of slaves were noisily chopping wood. Then they came to the stockade of close-set pointed poles. A guard sergeant in a red-trimmed blue jacket, armed with a revolver, met them with a salute which Kiro Soran returned: he unfastened the gate and motioned four or five riflemen into positions from which they could fire in between the poles in case the slaves turned on their new owners.

There seemed little danger of that, though Kiro Soran kept his hand close to the butt of his revolver. The slaves, an even hundred of them, squatted under awnings out of the sun, or stood in line to drink at the water-butt. They furtively watched the two men who had entered among them, as though expecting blows or kicks; when none were forthcoming, they relaxed slightly. As the labor foreman had said, they were clean and looked healthy. They were all nearly naked; there were about as many women as men, but no children or old people.

Radd's right, the captain told the new manager. They're not local. Much darker skins, and different face-structure; faces wedge-shaped instead of oval, and differently shaped noses, and brown eyes instead of black. I've seen people like that, somewhere, but

He fell silent. A suspicion, utterly fantastic, had begun to form in his mind, and he stepped closer to a group of a dozen-odd, the manager following him. One or two had been unmercifully lashed, not long ago, and all bore a few lash-marks. Odd sort of marks, more like burn-blisters than welts. He'd have to have the Company doctor look at them. Then he caught their speech, and the suspicion was converted to certainty.

These are not like the others: they wear fine garments, and walk proudly. They look stern, but not cruel. They are the real masters here; the others are but servants.

He grasped the manager's arm and drew him aside.

You know that language? he asked. When the man called Dosu Golan shook his head, he continued: That's Kharanda; it's a dialect spoken by a people in the Ganges Valley, in India, on the Kholghoor Sector of the Fourth Level.