Contents

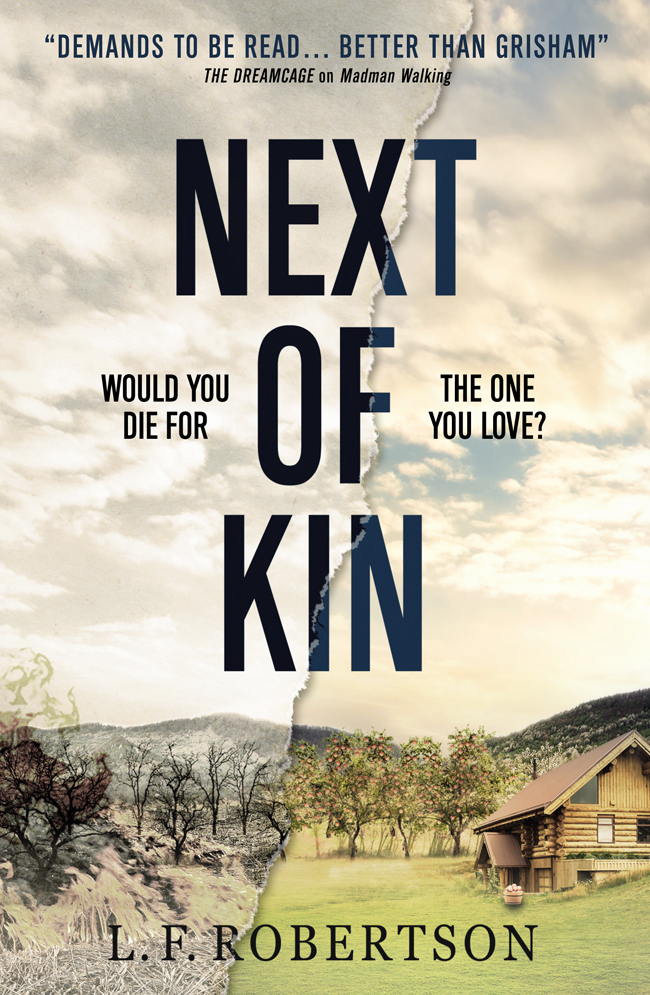

NEXT

OF

KIN

The Janet Moodie series from L.F. Robertson and Titan Books

Two Lost Boys

Madman Walking

Next of Kin

NEXT

OF

KIN

L.F. ROBERTSON

TITAN BOOKS

NEXT OF KIN

Print edition ISBN: 9781785659126

E-book edition ISBN: 9781785659133

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: June 2019

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright 2019 by L.F. Robertson. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

To Morgan

Harrison, California, isnt a place known for murders, the way, say, Stockton is, or Bakersfield. Its a typical Central Valley town, a generous sprawl of low buildings laid down over the last century and a half on the vast ancient seabed that forms the middle of the state. It has its old downtown, with fortress-like former banks now housing antique malls, boutiques in 1920s storefronts, and an old-fashioned movie theater, complete with a neon-lit tower, marquee and ticket booth, that now shows indie films. Off the beaten track these days, Old Town is a place where residents take visiting relatives to shop for California wine, olive oil, souvenirs, and Depression-era kitchen gadgets, and eat osso bucco and cannelloni at the old-school Italian restaurant or drink craft beer at the edgy new brewpub in a building that used to be a speakeasy. The neighborhoods around it are a mix of shabby apartment complexes and older run-down cottages, many of them rentals occupied by families who make their living as farmworkers or store clerks.

The present commercial center of town is Sequoia Avenue,a wide boulevard edged with office buildings, real estate offices, law firms, and strip malls, flanked by subdivisions of placid suburban houses on generous, tree-shaded lots. Unlike some similar towns which have withered as railroad traffic diminished and highways bypassed them, Harrison got lucky: its the county seat of Hartwell County, and a major highway runs along its edge.

Hartwell County came into existence in the great drought of the 1860s that broke up the vast Mexican land grants and opened the valley to Basque sheep herders and Swiss-Italian dairy farmers. During the Civil War the area held a pocket of Confederate sympathizers in a state that went with the Union; Harrison is named for a town in Arkansas. In the 1930s, in the middle of the Great Depression, Hartwell County attracted Dust Bowl migrants from Arkansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma, searching for any work they could get on the ranches, truck farms, and fruit orchards that support its prosperity. The Ku Klux Klan marched there as late as the 1980s, and the white people in Hartwell County (there are very few African-Americans) still retain something of the South in their speech, religion, and politics.

A few minutes outside town are the miles of well-kept orchardspeaches, walnuts, pistachios, pomegranates, oranges, lemons, grapesset in a grid of numbered two-lane roads, and here and there a stretch of pasture behind an old wood and wire fence or a house and outbuildings down a long private drive. The rows of trees and tracts of open land along the roads are interrupted now and then byragtag farm towns of small stucco houses with front yards of dirt and dry weeds, paint peeling from wood trim, air conditioners in their windows or old swamp coolers on their roofs, and pickup trucks parked in their driveways. The towns main streets are a row of liquor stores, thrift shops, bodegas, churches, and shops that repair things: cars, farm equipment, wells and septic tanks, household appliances.

Sunny Ferrante grew up in one of those dusty little towns, a dot on the map twelve miles outside Harrison, called Sparksville. She may be the most famous of its alumnae; almost certainly, shes the only one to have landed on death row. A long time ago, she had been my client, and now she was again.

Carey Bergmann collared me during a continuing education seminar about criminal appeals, as I waited in line outside the restroom. Janet! she said, startling me from my reverie about the new changes in the felony murder rule.

I looked up. Carey? Not that I needed to ask; she hadnt changed much since Id last seen her. I tried to remember how long it had beenseven years? Ten?

Id like to talk to you, she said. When you have a moment.

I saw her a couple of minutes later, as I left the line of coffee urns with a fresh cup to get me, I hoped, through the rest of the morning. She was talking with Joe Hamilton, one of the days speakers, but she excused herself and hurried over to meet me.

Im so glad to see you here today, she said, as we found our way to a couple of empty chairs. I was going to call you. As we walked, I had a chance to look at her more closely. She really hadnt changed mucha little thinner, maybe, and more tanned in the face. She is taller than I am,perhaps five foot six, and she still moved with an athletic grace and physical confidence that has always eluded me.

Its been a while, she said, when wed both sat down. I dont think Ive seen you since Terrys memorial. That was really a shock. We all thought the world of him; he was an inspiration for me. How are you doing?

Not bad, I said, with a shrug. Terry, my husband, had committed suicide seven years ago. It wasnt something I generally cared to talk about. I live a dull life.

I hope not, she said. Jim Christie says youre living way out in the woods in, like, Mendocino, and you and he have a habeas corpus case together.

You know Jim? The community of death penalty lawyers was really a small world, I thought.

Yeah. I tried a case with him once, and we run into each other in court sometimes. Is he keeping you busy?

Not right now, I said, with what I hoped was a noncommittal shrug.

She gave a short laugh. Hes a regular Tom Sawyer. He has a gift for getting other people to do his work.

I nodded. But were almost finished. The petition in that case was filedoh, God, two years agoand were waiting for the court to act. So Im in a bit of a lull, I guess, doing appeals and not much else.

Oh, good. You remember Sunny Ferrante?

Wow, Sunny. That was a long time ago.

2002. She was sentenced in 2004.

Right. It was a cold casecapital appeals move ata glacial pace through the legal systemand a twisted, sordid one: on a spring day in 2002, Sunnys husband, Greg Ferrante, a local real-estate developer, had been found dead next to the swimming pool behind his house, a single bullet in the back of his head. Suspicion fell immediately on Sunny, especially since the local rumor mill had it that Greg had been about to leave her for a younger woman. But she had a solid alibi for the time of the crime. With no evidence and no other suspects, the case sat unsolved for several months, until a local petty malefactor in jail on a charge of his own told a guard that Sunnys daughters boyfriend, a kid named Todd Betts, had confessed the murder to him, saying hed been hired by Sunny to kill her husband. As bad luck would have it, Sunny had loaned Todd several thousand dollars to repair his truck, a month after the murder. And a month or so after that Todd had died of a drug overdose. The evidence against Sunny was thin, but enough to move an outraged jury to convict her of Gregs murder and give her the death penalty.