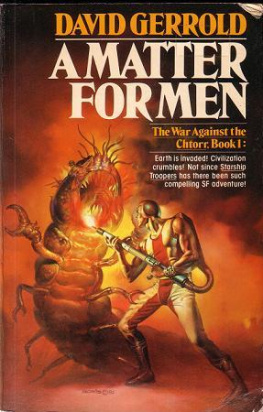

A Day for Damnation

The War Against the Chtorr

Book 2

David Gerrold

For the Mccaffreys, Anne, Gigi, Todd, and Alec, with love

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

DAVID GERROLD began his science fiction career in 1967, as a writer for Star Trek. His first sale was the episode entitled "The Trouble with Tribbles," one of the most popular episodes in the show's history.

Gerrold later wrote two nonfiction books about Star Trek: The World of Star Trek, the first in-depth analysis of the show, and The Trouble with Tribbles, in which he shared his personal experiences with the series. Gerrold has since written many other TV scripts, including episodes of Logan's Run, Land of the Lost, and the Star Trek animated TV series. He has served as story editor for Land of the Lost and Buck Rogers.

Gerrold is also a well-established science fiction novelist. His bestknown works are When Harlie Was One and The Man Who Folded Himself, both of which were nominated for the Hugo and Nebula awards. He's published eight other novels, five anthologies, and a short story collection. In 1979, he won the Skylark Award for imaginative fiction.

David Gerrold is forty years old and lives in Los Angeles with three peculiar dogs, two and a half cats, a computer with delusions of sentience, and a butterscotch convertible. Gerrold is a skilled programmer and contributes occasionally to Creative Computing, Infoworld, and other home-computing periodicals.

He also writes a monthly column on science fiction for Starlog magazine.

Gerrold is currently at work on Book Three of The War Against the Chtorr: A Rage for Revenge.

Chtorr (ktor) n.

1. The planet Chtorr, presumed to exist within 30 light-years of Earth.

2. The star system in which the planet occurs; a red giant star, presently unidentified.

3. The ruling species of the planet Chtorr; generic.

4. In formal usage, either one or many members of same; a Chtorr, the Chtorr. (See Chtor-ran)

5. The glottal chirruping cry of a Chtorr.

Chtor-ran (ktor-en) adj.

1. Of or relating to either the planet or the star system, Chtorr.

2. Native to Chtorr.

n.

1. Any creature native to Chtorr.

2. In common usage, a member of the primary species, the (presumed) intelligent life form of Chtorr. (pl. Chtor-rans)

-The Random House Dictionary of the English Language, Century 21 Edition, unabridged

ONE

THE CHOPPER looked like a boxcar with wings, only larger. It squatted in the middle of the pasture like a pregnant sow. Its twin rotors stropped the air in great slow whirls. I could see the tall grass flattening even from here.

I turned away from the window and said to Duke, "Where the hell did that come from?"

Duke didn't even look up from his terminal. He just grinned and said, "Pakistan." He didn't even stop typing.

"Right," I said. There wasn't any Pakistan any more, hadn't been a Pakistan for over ten years. I turned back to the window. The huge machine was a demonic presence. It glowered with malevolence. And I'd thought the worms were nasty to look at. This machine had jet engines large enough to park a car in. Its stubby wings looked like a wrestler's shoulders.

"You mean it was built for the Pakistan conflict?" I asked.

"Nope. It was built last year," corrected Duke. "But it was designed after Pakistan. Wait one minute-" He finished what he was doing at the terminal, hit the last key with a flourish, and looked up at me.

"Remember the treaty?"

"Sure. We couldn't build any new weapons."

"Right," he said. He stood up and slid his chair in. He turned around and began picking up pages as they slid quietly, one after the other, out of the printer. He added, "We couldn't even replace old weapons.

But the treaty didn't say anything about research or development, did it?"

He picked up the last page, evened the stack of papers on a desk top, and joined me at the window.

"Yep. That is one beautiful warship," he said.

"Impressive," I admitted.

"Here-initial these," he said, handing me the pages.

I sat down at a desk and began working my way through them. Duke watched over my shoulder, occasionally pointing to a place I missed. I said, "Yeah, but-where did it come from? Somebody still had to build it."

Duke said, "Are your clothes custom made?"

"Sure," I said, still initialing. "Aren't everybody's?"

"Uh huh. You take it for granted now. A computer looks at you, measures you by sight, and appropriately proportions the patterns. Another computer controls a laser and cuts the cloth, and then a half-dozen robots sew the pieces together. If the plant is on the premises, you can have a new suit in three hours maximum."

"So?" I signed the last page and handed the stack back to him. He put the papers in an envelope, sealed it, signed it, and handed it back to me to sign.

"So," he said, "if we can do it with a suit of clothes, why can't we do it with a car or a house-or a chopper? That's what we got out of Pakistan. We were forced to redesign our production technology."

He nodded toward the window. "The factory that built that Huey was turning out buses before the plagues. And I'll bet you the designs and the implementation plans and the retooling procedures were kept in the same state of readiness as our Nuclear Deterrent Brigade for all those years-just in case they might someday be needed."

I signed the envelope and handed it back.

"Lieutenant," Duke grinned at me, "you should sit down and write a thank-you note to our friends in the Fourth World Alliance. Their so-called `Victory of Righteousness' ten years ago made it possible for the United States to be the best-prepared nation on this planet for responding to the Chtorran infestation."

"I'm not sure they'd see it that way," I remarked.

"Probably not," he agreed. "There's a tendency toward paranoia in the Fourth World." He tossed the envelope into the safe and shut the door.

"All right-' he said, suddenly serious. "The paperwork is done." He glanced at his watch. "We've got ten minutes. Sit down and clear." He pulled two chairs into position, facing each other. I took one and he took the other. He took a moment to rub his face, then he looked at me as if I were the only person left on the planet. The rest of the world, the rest of the day, all of it ceased to exist. Taking care of the soul, Duke called it. Teams had gone out that hadn't and they hadn't come back.

Duke waited until he saw that I was ready to begin, then he asked simply, "How are you feeling?"

I looked inside. I wasn't certain.

"You don't have to hit the bull's-eye," Duke said. "You can sneak up on it. How are you feeling?" he asked again.

"Edgy," I admitted. "That chopper out there-it's intimidating. I mean, I just don't believe a thing that big can get off the ground."

"Mm hm," said Duke. "That's very interesting, but tell me about James McCarthy."

"I am-" I said, feeling a little annoyed. I knew how to clear. You dump your mind of everything that might get in the way of the mission.

"There-" pointed Duke. "What was that?"

I saw what he meant. I couldn't hide it. "Impatience," I said. "And annoyance. I'm getting tired of all the changes in procedures. And frustrated-that it doesn't seem to make a difference-"

"And ... ?" he prompted.

"And..." I admitted, "...sometimes I'm afraid of all the responsibility. Sometimes I just want to run away from it. And sometimes I want to kill everything in sight." I added, "Sometimes I think I'm going crazy."

Duke looked up sharply at that, but his phone beeped before he could speak. He pulled it off his belt, thumbed it to life, and snapped, "Five minutes." He put it down on the table and looked at me. "What do you mean?"