T hey were schooled at Eton and Harrow, Cambridge and Oxford. They lived in Belgravia and Mayfair and spent their weekends at sprawling country houses in Kent, Sussex, and Oxfordshire. They were part of the small, clubby network that dominated English society. And now, in May 1940, these Tory members of Parliament were doing the unthinkable: trying to topple Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, the leader of their own party, from power.

They knew they were courting political suicide. They were challenging a powerful, authoritarian prime minister who equated criticism of his policies with treason and employed a full complement of dirty tricks to stamp out dissent. Opponents branded the rebels as unpatriotic. Sir Samuel Hoare, the home secretary, denounced them as jitterbugs and claimed that their alarm-and-scare-mongering had thwarted a new golden age of tranquility in Europe.

Like other former public-school boys, the small band of backbenchers had been taught to value loyalty. But in the current crisis, they believed, they owed loyalty to their country, not to their party or prime minister. For eight months Britain had been at war with Germany, a war that Chamberlain and his government clearly had no interest in fighting, a war being waged, as one Tory rebel said, without arms, without faith, and without heart.

Defending Poland was the ostensible reason why Britain and France had declared war on Hitlers Germany the previous September. But Poland had been quickly devastated by the German invasion, and its Western allies, despite all the treaties and all the promises to that shattered country, did nothing to save it. Was there any other justification for continuing this putative conflict? If so, Chamberlains government never said what it was. The government declined to declare its war aims and seemed to prefer a token war, waged as cheaply as possible. The British Army was undermanned, ill equipped, and badly organized. Mobilization was lethargic; able-bodied men were still working as chauffeurs and as doormen at Londons private clubs and luxury hotels. Armament production was proceeding at a snails pace, and few, if any, controls had been imposed on civilian manufacturing.

Throughout Great Britain, there was doubt, cynicism, apathy, and distrust. When war was declared, the British braced themselves to bear the shock, believing their cause was just. But when their leaders turned their backs on Poland and nothing more happened, the sense of mission evaporated. More than a million city dwellers had been evacuated to the countryside; a blackout had been imposed, causing tremendous disruption and dangerand for what? Where were the bombs? What was the rationale for turning everyones life upside down? Why were the wealthy still throwing lavish parties and drinking champagne at posh nightclubs while workers struggled with shortages and skyrocketing costs? To his radio listeners in America, the CBS correspondent Edward R. Murrow reported that the people of Britain felt the machine is out of control, that we are all passengers on an express train traveling at high speed through a dark tunnel toward an unknown destiny. The suspicion recurs that the train may have no engineer, no one who can handle it.

Hitler, meanwhile, had no doubts about where he was heading. His forces had taken full advantage of the inertia of Britain and France, knifing through Poland the previous autumn, then, in April, invading Denmark and routing the British Army and Royal Navy from Norway. German troops were now poised to launch a lightning sweep through the heart of Western Europe, striking toward the English Channel.

Socially and militarily, Britain teetered on the edge of disaster. Yet there appeared to be little hope for change. Chamberlain was determined to stay in power, and most of the massive Tory majority in the House of Commons seemed determined to support him. So were the BBC and the nations newspapers. Such support was in the national interest, editors rationalized. Criticizing the government in time of war would be disloyal, they declared, splitting the country further and only helping the Germans.

This, then, was what the Tory insurgents faced as they plotted to oust Neville Chamberlain. It was the climax of a two-year struggle against his policy of appeasement of Nazi Germany that had begun with the resignation of Anthony Eden as foreign secretary in February 1938. The fight had been bitter and intensely personal. The rebels were challenging men who had been their comrades in school, who belonged to the same clubs, who in some cases were members of their own families. They were violating the gentlemanly norms of their society; for that, they were vilified as traitors to their party, government, class, and country. Among the rebels themselves, there were deep divisions and dissension. They had trouble finding a leader; only after the war had begun did a senior colleague finally step forward with the courage and conviction to head the revolt.

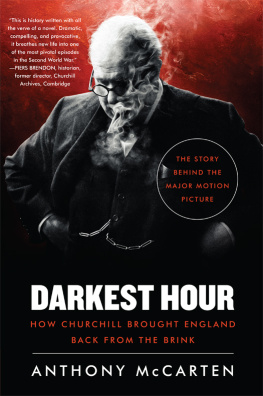

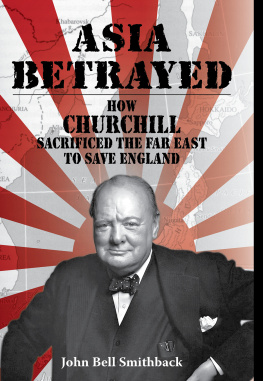

That leader was not Winston Churchill. Indeed, the Tory dissidents had been given no help at all by the man who once had been the foremost critic of Chamberlains appeasement policy. When war was declared, Churchill joined the cabinet as first lord of the admiralty. In the months that followed, although he pressed hard in government councils for a more vigorous prosecution of the war, he remained loyal to the prime minister. To the dismay of his anti-appeasement colleagues, Churchill made clear he would do nothing to help bring Chamberlain down. If the prime minister was to be toppled, it must be their doing, not his.

The climax of the anti-Chamberlain movement would come on a soft, golden spring afternoon in early May, when members of the House of Commons gathered to debate Britains humiliating defeat in Norway. It was the final showdown between the prime minister and the Tory rebels, joined by their newfound Labour, Liberal, and Independent allies. As they worked feverishly before the debate to line up last-minute support, the rebels knew that the odds of their succeeding were regarded as slim to none. According to Time magazine, nobody thought on that first afternoon of debate that there was more than an outside chance of dislodging Chamberlain.

Yet three days later Neville Chamberlain was gone, and Winston Churchill was prime minister. This is the story of how that came to beand the men who made it happen.

The idea for Troublesome Young Men grew out of research for two previous books that I wrote with my husband, Stanley Cloud, both of them touching on the climactic summer of 1940 in Britain. It was during those terrible yet glorious days that the epic of Winston Churchill really began. You ask what is our aim? he declared to the House of Commons on May 13, three days after replacing Chamberlain. I can answer in one word: victory. That word remained his touchstone, even as France fell, British troops retreated to Dunkirk, and a German invasion of Britain seemed to loom on the horizon. When Luftwaffe bombers began their assault on Britain later that summer, the new prime minister rallied his countrymen to greatness.

The story of Winston Churchill in 1940 is, without question, one of the most compelling dramas in modern British history. But as I researched the period in more detail, it seemed to me that the behind-the-scenes story leading to Churchills accessionthat of the Tory rebels defying their party and prime ministeris, in its way, no less significant or engrossing. For if it hadnt been for those MPs, and for the parliamentary colleagues who joined their ranks in the Norway debate, Churchill would never have been given the chance to rise so magnificently to the challenge, and Britain might well have negotiated for peace with Hitler or even gone down to defeat.