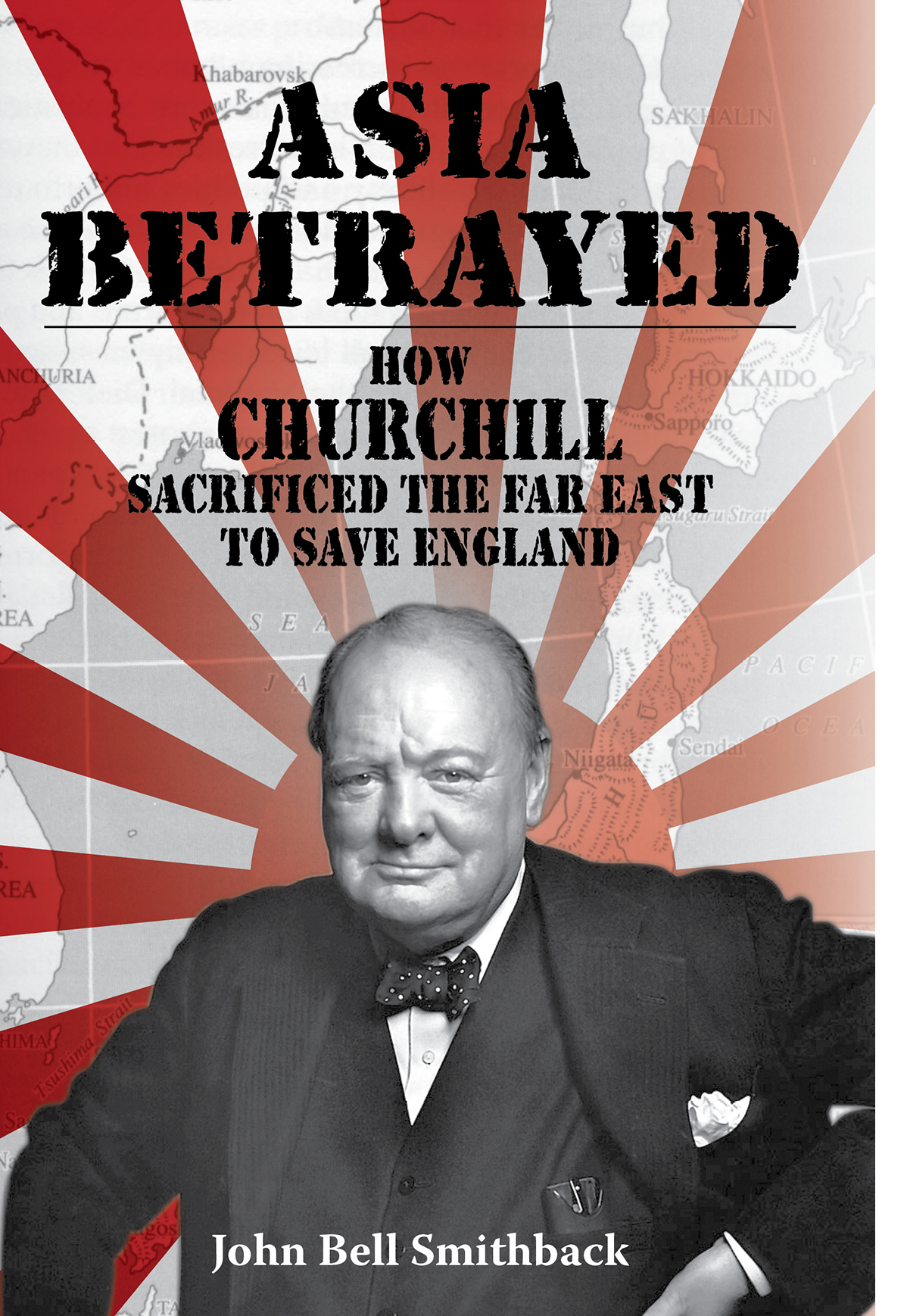

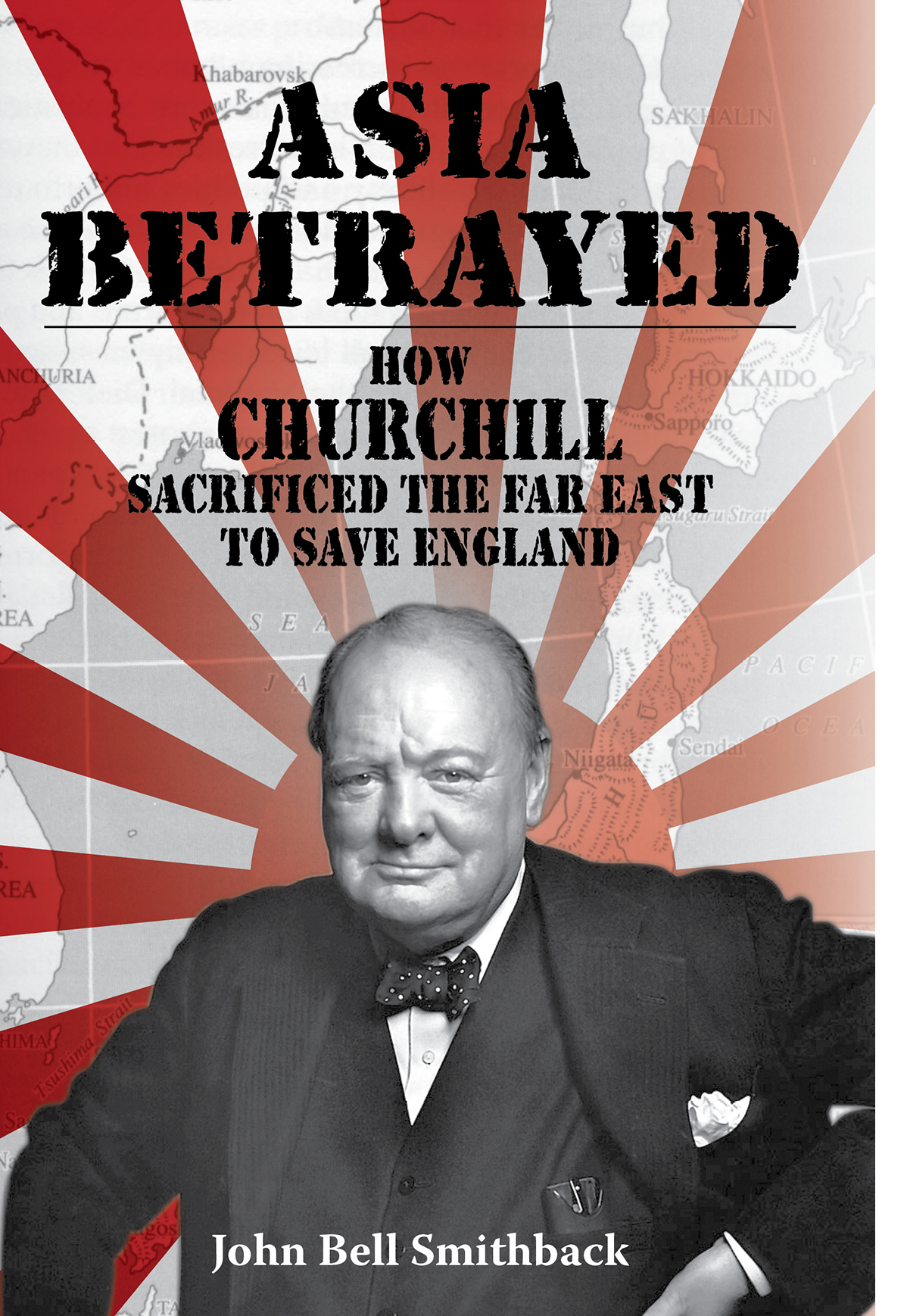

Asia Betrayed

By John Bell Smithback

ISBN-13: 978-988-8422-60-9

2017 John Bell Smithback

Cover design: Jason Wong

HISTORY / Asia

EB093

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in material form, by any means, whether graphic, electronic, mechanical or other, including photocopying or information storage, in whole or in part. May not be used to prepare other publications without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information contact info@earnshawbooks.com

To Ching Yee,

whose parents & lived it.

And my thanks to Graham Earnshaw,

a tough and demanding editor

who had the patience to see it through.

PART I

Malaya - Singapore

Hong Kong

There are clear signs that Japan does not know which

way to turn. Tojo is scratching his head. There are no

signs that Japan is going to attack anyone.

Sir Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham

Commander-in-Chief Far East,

Singapore, December 5, 1941

It was December 1941 and Singapore stood as an intrepid symbol of the greatness of Britains wandering lion. Even its name in Sanskritliterally Lion City seemed to attest to the might of the sprawling Empire that controlled it. To the north, Japan was rattling a mighty saber and the sounds it made created disquieting echoes that reached beyond Asia. But Japan was far away, and Singapore felt secure. In London, Prime Minister Winston Churchill had spoken proudly of Singapore as that great bastion of Empire, the Gibraltar of the East, and he and the world seemed convinced that Singapore was, as he said, an invincible fortress.

Certainly, few within Britains 140,000-strong military force and in her colonies doubted the truth of Churchills words. They listened to his declarations and were persuaded that Japan would not risk national suicide in a bid to grab land on the Malay Peninsula.

The man in the street was listening too, and though he may have had apprehensions, he was prepared to accept those two eloquent tags of impregnability and invincibility . If he admitted to flashes of doubt about Singapores ability to resist a Japanese attack, those wavering moments were promptly dismissed when the news assured him that Singapore was beyond the flying range of any Japanese bomber.

The men of Britains army, navy and air force had been made aware of that too. We think it unlikely that Japan will enter the war against Great Britain and the USA, Churchill assured his top admirals. It is still more unlikely that they would attempt any serious land operations in Malaya. In more recent weeks they were doubly assured when their commanders briefed them on recent medical findings that declared that Japanese pilots had remarkably weak eyesight which limited their ability to distinguish distant objects. That, of course, helped to explain why so many Japanese people wore eyeglasses. Of greater significance was a reported fresh discovery by a military medical team in London that the Japanese were unable to see in the dark.

And so, on that mild December night in 1941, the 550,000 citizens of Singapore went to bed believing that they were adequately protected, that their way of life was guarded, and that the probability of war was very low.

The events leading up to that momentous night had begun four-and-a-half years earlier with Japans contrived excuse for an invasion of China when it used the claim that one of its soldiers was missing and presumably being held captive to begin bombarding the Chinese at the Marco Polo Bridge near Beijing. Japan had already occupied Manchuria in 1932 after staging a phony bomb attack and had installed Chinas last Emperor, Henry Pu-yi, on an invented throne with a concocted title, effectively annexing Chinas three northeastern provinces. But in the dead of night on the seventh of July, 1937, Japanese troops at the Marco Polo Bridge launched a full-scale invasion of China in an undeclared war.

That date also marked the moment when a coalition of Japanese military and naval officers swept aside the civilian cabinet in Tokyo and took control of the government. Acting in the name of the Emperor of Japan, it established a unit named the Cabinet Advisory Council to Conduct the Direction of the War . Anyone who dared to voice disagreement with the Council or question the actions of the militaryor anyone suspected of liberal tendencies of any kindwas subject to immediate arrest. In a word, Japan had ceased to be a constitutional government and had become a military dictatorship. And as the war with China advanced, Japan began to appear increasingly menacing to her Asian neighbors.

They had every reason to be alarmed. In the event of future hostilities with Japan, a horrifying example of what could be expected occurred after the fall of Nanking in December 1937. From that point on, there was a significant shift in Japanese thinking as it began waging a brutal campaign of national hate against the Chinese, and the appalling acts of violence that followed became part of a deliberate policy established by Lieutenant General Prince Yasuhiko Asaka, an uncle-in-law to Emperor Hirohito. Termed Sook Ching (meaning purge through purification ), it was calculated to achieve two ends: to eliminate anyone considered anti-Japanese, and to show what awaited anyone who refused to willingly submit to Japanese domination.

Asakas order was to kill all prisoners, and in less than six weeks perhaps as many as 350,000 civilians in the city were slaughtered. The exact number will never be known because the Japanese destroyed all records of their butchery. The event, downplayed or totally denied by some in Japan today, has become known as the Rape of Nanking, and it ranks as one of the worst massacres of the 20th century. To General Asaka, however, mass murder was, like bullets, bombs or poison gas, merely another weapon of war.

So, too, was rape, as his frenzied soldiers were allowed to go on a hysterical rampage savaging between 35-40,000 women, many of whom were subsequently killed. Those who escaped death were often forced into sexual slavery as Comfort Women for Japanese soldiers.

Asakas tactics achieved their desired result, and in Hangchow, Shanghai, Amoy, Cantonand wherever else the Japanese were to set their boots in Asiathe horrors of Nanking were repeated over and over again, though never on such a horrific scale. And in every instance, just as the periods of chaos peaked, Japanese leaders took control, established order, introduced food rationing, printed new money, policed the citiesand blamed the mayhem and carnage on the defeated white colonialists. All of which, they declared, proved that Japans New Asian Order was right.

Over the next eight years of war, it became increasingly difficult to keep the many atrocities in perspective for, in the Japanese mind, any act of cruelty could be condoned. It was part of the Bushido code, a feudal military ethic which maintained that the Emperor of Japan was a divine being, that Japan was a divine country, and that both had a divine mission to fulfill. For soldier and citizen alike, Bushido taught that life was but a feather, a mere raindrop upon a vast sea. Glory was achieved by dying for the Emperor, and the death of an enemy mattered not at all.