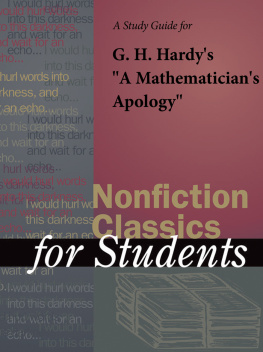

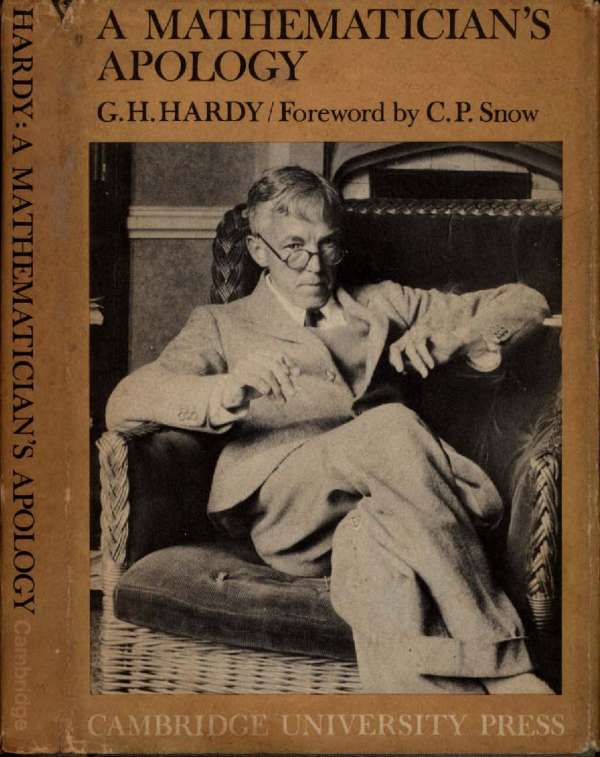

Hardy - A mathematicians apology

Here you can read online Hardy - A mathematicians apology full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Cambridge, year: 2017, publisher: Cambridge University Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A mathematicians apology

- Author:

- Publisher:Cambridge University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- City:Cambridge

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A mathematicians apology: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A mathematicians apology" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Acrobat 7 Pdf 15.6 Mb.

Scanned by artmisa using Canon DR2580C + flatbed option

Hardy: author's other books

Who wrote A mathematicians apology? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

A mathematicians apology — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A mathematicians apology" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

A MATHEMATICIAN'S APOLOGY

G. H. HARDY FOREWORD BY C. P. SNOW

"It was a perfectly ordinary night at Christ's high table, except that Hardy was' dining as a guest. He had just returned to Cambridge as Sadleirian professor, and I had heard something of him from young Cambridge mathematicians. They were delighted to have him back: he was a real mathematician, they said, not like those Diracs and Bohrs the physicists were always talking about: he was the purest of the pure. He was also unorthodox, eccentric, radical, ready to talk about anything."

So writes C. P. Snow in his introduction to this reissue of a book that has long been treasured by mathematicians,and others to whom mathematics is an attractive mystery.

The book is a personal account by a distinguished mathematician of what mathematics meant to him as a man. Hardy discusses and illustrates the attractive force of mathematics. He dismisses its utility but describes its depth and beauty as a creative art.

Hardy asks: Is it worth man's while to give his life to the study of mathematics ? His answer is of necessity personal, and indeed that is the book's value. It holds the confessions of an unrepentant but humane mathematician; his candid integrity and good humour make a finite addition to the sum of human thought.

4>

15s net in U.K.

MATHEMATICIAN'S APOLOGY

BY

G. H. HARDY

WITH A FOREWORD BY

C. P. SNOW

CAMBRIDGE AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS

Published by the Syndics of the Cambridge University Press

Bentley House, 200 Euston Road, London, N.W. 1.

American Branch: 32 East 57th Street, New York, N.Y. 10022

Foreword C. P. Snow 1967

First Edition 1940

Reprinted 194.1

1948

Reprinted with Foreword by G. P. Snow 1967

To

JOHN LOMAS who asked me to write it

Printed by offset lithography in the United States of America

FOREWORD

It was a perfectly ordinary night at Christ's high table, except that Hardy was dining as a guest. He had just returned to Cambridge as Sadleirian professor, and I had heard something of him from young Cambridge mathematicians. They were delighted to have him back: he was a real mathematician, they said, not like those Diracs and Bohrs the physicists were always talking about: he was the purest of the pure. He was also unorthodox, eccentric, radical, ready to talk about anything. This was 1931, and the phrase was not yet in English use, but in later days they would have said that in some indefinable way he had star quality.

So, from lower down the table, I kept studying him. He was then in his early fifties: his hair was already grey, above skin so deeply sunburnt that it stayed a kind of Red Indian bronze. His face was beautifulhigh cheek bones, thin nose, spiritual and austere but capable of dissolving into convulsions of internal gamin-like amusement. He had opaque brown eyes, bright as a bird'sa kind of eye not uncommon among those with a gift for conceptual thought. Cambridge at that time was full of unusual and distinguished faces

but even then, I thought that night, Hardy's stood out.

I do not remember what he was wearing. It may easily have been a sports coat and grey flannels under his gown. Like Einstein, he dressed to please himself: though, unlike Einstein, he diversified his casual clothing by a taste for expensive silk shirts.

As we sat round the combination-room table, drinking wine after dinner, someone said that Hardy wanted to talk to me about cricket. I had been elected only a year before, but Christ's was then a small college, and the pastimes of even the junior fellows were soon identified. I was taken to sit by him. I was not introduced. He was, as I later discovered, shy and self-conscious in all formal actions, and had a dread of introductions. He just put his head down as it were in a butt of acknowledgment, and without any preamble whatever began:

'You're supposed to know something about cricket, aren't you?' Yes, I said, I knew a bit.

Immediately he began to put me through a moderately stiff viva. Did I play? What sort of performer was I? I half-guessed that he had a horror of persons, then prevalent in academic society, who devotedly studied the literature but had never played the game. I trotted out my credentials, such as they were. He appeared to

find the reply partially reassuring, and went on to more tactical questions. Whom should I have chosen as captain for the last test match a year before (in 1930)? If the selectors had decided that Snow was the man to save England, what would have been my strategy and tactics? ('You are allowed to act, if you are sufficiently modest, as non-playing captain.') And so on, oblivious to the rest of the table. He was quite absorbed.

As I had plenty of opportunities to realize in the future, Hardy had no faith in intuitions or impressions, his own or anyone else's. The only-way to assess someone's knowledge, in Hardy's view, was to examine him. That went for mathematics, literature, philosophy, politics, anything you like. If the man had bluffed and then wilted under the questions, that was his lookout. First things came first, in that brilliant and concentrated mind.

That night in the combination-room, it was necessary to discover whether I should be tolerable as a cricket companion. Nothing else mattered. In the end he smiled with immense charm, with child-like openness, and said that Fenner's (the university cricket ground) next season might be bearable after all, with the prospect of some reasonable conversation.

Thus, just as I owed my acquaintanceship with Lloyd George to his passion for phrenology, I

owed my friendship with Hardy to having wasted a disproportionate amount of my youth on cricket. I don't know what the moral is. But it was a major piece of luck for me. This was intellectually the most valuable friendship of my life. His mind, as I have just mentioned, was brilliant and concentrated: so much so that by his side anyone else's seemed a little muddy, a little pedestrian and confused. He wasn't a great genius, as Einstein and Rutherford were. He said, with his usual clarity, that if the word meant anything he was not a genius at all. At his best, he said, he was for a short time the fifth best pure mathematician in the world. Since his character was as beautiful and candid as his mind, he always made the point that his friend and collaborator Littlewood was an appreciably more powerful mathematician than he was, and that his protege Ramanujan really had natural genius in the sense (though not to the extent, and nothing like so effectively) that the greatest mathematicians had it.

People sometimes thought he was under-rating himself, when he spoke of these friends. It is true that he was magnanimous, as far from envy as a man can be: but I think one mistakes his quality if one doesn't accept his judgment. I prefer to believe in his own statement in A Mathematician's Apology, at the same time so proud and so humble:

1 1 still say to myself when I am depressed and

find myself forced to listen to pompous and tiresome people, "Well, I have done one thing you could never have done, and that is to have collaborated with Littlewood and Ramanujan on something like equal terms."'

In any case, his precise ranking must be left to the historians of mathematics (though it will be an almost impossible job, since so much of his best work was done in collaboration). There is something else, though, at which he was clearly superior to Einstein or Rutherford or any other great genius: and that is at turning any work of the intellect, major or minor or sheer play, into a work of art. It was that gift above all, I think, which made him, almost without realizing it, purvey such intellectual delight. When A Mathematician's Apology was first published, Graham Greene in a review wrote that along with Henry James's notebooks, this was the best account of what it was like to be a creative artist. Thinking about the effect Hardy had on all those round him, I believe that is the clue.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A mathematicians apology»

Look at similar books to A mathematicians apology. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A mathematicians apology and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.