ALSO BY DEIRDRE BAIR

Al Capone: His Life, Legacy, and Legend

Saul Steinberg: A Biography

Calling It Quits: Late-Life Divorce and Starting Over

Jung: A Biography

Anas Nin: A Biography

Simone de Beauvoir: A Biography

Samuel Beckett: A Biography

Copyright 2019 by Deirdre Bair

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.nanatalese.com

DOUBLEDAY is a registered trademark of Penguin Random House LLC. Nan A. Talese and the colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

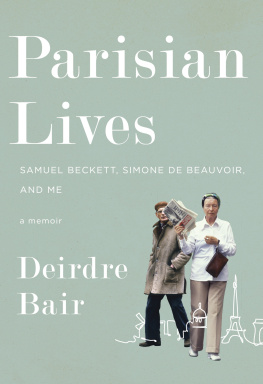

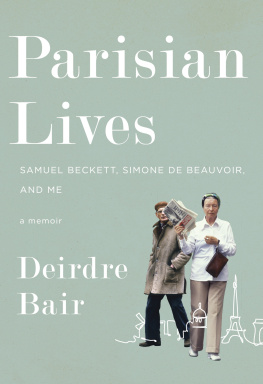

Cover image: Samuel Beckett by Thierry Orban/Sygma and Simone de Beauvoir by Franois Lochon/Gamma-Rapho, both Getty Images; (skyline) Stockleb/Shutterstock

Cover design by Michael J. Windsor

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bair, Deirdre, author.

Title: Parisian lives : Samuel Beckett, Simone de Beauvoir, and me : a memoir / Deirdre Bair.

Other titles: Samuel Beckett, Simone de Beauvoir, and me : a memoir

Description: First edition. | New York : Nan A. Talese / Doubleday, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019006879 (print) | LCCN 2019021111 (ebook) | ISBN 9780385542463 (ebook) | ISBN 9780385542456 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Bair, Deirdre. | Women authors, AmericanBiography. | Authors, American20th centuryBiography. | AutobiographyWomen authors. | Biography as a literary form. | Beckett, Samuel, 19061989Psychology. | Beauvoir, Simone de, 19081986Psychology. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Personal Memoirs. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Literary. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Women.

Classification: LCC PS3602.A5635 (ebook) | LCC PS3602.A5635 Z46 2019 (print) | DDC 818/.5403 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019006879

Ebook ISBN9780385542463

v5.4

ep

Contents

FOR AILEEN WARD,

Mentor and Friend

PREFACE

Whenever I meet someone new and tell them that I have written biographies of Samuel Beckett and Simone de Beauvoir, their first question is usually What made you choose those subjects? Ive honed a ready answer over the years, one designed to be brief and polite and to let me change the subject. They were remarkable people, I say. Truly extraordinary. Great privilege to have known them. Most of the time I dont get away with it, and the question that routinely follows is What were they really like? That one is never easy to answer.

Over the years I wrote several other biographies about equally fascinating people, but the interest in Beckett and Beauvoir remained out of proportion to all the rest. With every lecture or seminar, I found myself fielding questions about what was it like to be with them, and what did we talk about, and why did I write the books as I did. I was bombarded with remarks along the lines of Werent you awestruck, terrified, humble, wowedyou pick the adjective hereto be in the presence of Samuel Beckett and Simone de Beauvoir? Yes, I admit; yes, I felt all those emotions and many more besides. I cant count how many times I was asked to sing for my supper at dinners and parties, or relate how hard I searched for anecdotes to amuse other guests without inappropriately revealing anything personal I had come to know about these literary giants.

But the questions persisted, and I began to think that perhapssomeday in the far distant futureperhaps I might write a little book, a book about the writing of the books. The original idea was to write something primarily for scholars and writers that would cover all my biographies, to concentrate on the decisions I made when dealing with structure and content, or how I worked in foreign archives and languages, or how I dealt with reluctant heirs and troublesome estates. Each time I suggested this possible project, even to fellow biographers or academics, the response was always Thats all very nice, but please just tell us what Beckett and Beauvoir were really like. And for many years that was something I simply could not bring myself to do.

I wrote those two biographies during the most eventful years of my own life, and to write about Beckett and Beauvoir meant that I would have to write about myself as well. If I described the professional decisions that I made, I would also have to describe the brash young woman I was then: a journalist not yet thirty who became an accidental biographer, one who had never read a biography before she decided that Samuel Beckett needed one and she was the person to write it. And I would have to tell of a somewhat wiser woman a decade later, who formed a feminist consciousness during tumultuous years when she worked hard to stay married, raise children, keep a household running, forge an academic career, and scrounge enough money to go to Paris to confer with Simone de Beauvoirbecause Simone de Beauvoir appeared to be the only contemporary role model who had made a success of both her personal and her professional lives, and I was searching desperately for someone to tell me how to do the same.

My writing life began as a reporter for newspapers and magazines. Even though it was the era of the New Journalism, I never adopted those techniques and kept myself scrupulously out of everything I wrote. That decision was largely made for me by the fact that I wrote hard news much of the timefrom actions of the zoning board of appeals to city council shenanigans, the sort of thing that allowed me to concentrate on the story at hand and not on the role I played in getting it. When I began to write biography, a biographer friend who also started in journalism told me how she melded her old career with the new one: Biographers are essentially storytellers. So, then, tell the story, but stay the hell out of it. Since that was my natural impulse, this approach suited me just fine until I became both source and subject.

In the last several years, I was contacted by several biographers whose subjects figured in my books, and thus in my life. I gave them interviews in which I described my interactions with their subjects, and I gave them letters, photos, and other documents to support what I told them. Imagine then my horror when their books were published and I was quoted and thanked effusively but with everything they attributed to me either twisted or subverted. I checked their notes to see if they were using multiple sources, for if so, the weight of information from others might explain how they had changed my testimony. But no, I was their only source, so it was obvious that they had contorted my words to support their theory or thesis. It put me in a terrible position, because much of what they wrote was simply not true. That was the moment when I began to give serious consideration to committing my own version of my working history to print, to set the record straight as I remember it and to let future generations of readers assess it and decide for themselves whether I was an objective witness and a reliable narrator. Or not.

And yet I was still not ready to confront my own story. I am sure I bored my sister-writers in the Women Writing Womens Lives seminar at CUNY, when I sought their counsel for the better part of a year as I asked repeatedly how I could bring myself to reveal so much that was personal, not only about Beckett and Beauvoir but about myself. For every embarrassing or unpleasant or unsavory aspect of their behavior, mine was at least doubly so. I had begun to write biography as a curious combination of seasoned, hardened journalist and total novice in the genre. Did I really want to put all the mistakes I made out there for the world to see? My dilemma was expressed perfectly when Margo Jefferson spoke to the seminar about her memoir,

![Samuel Beckett [Samuel Beckett] - The Complete Dramatic Works](/uploads/posts/book/72751/thumbs/samuel-beckett-samuel-beckett-the-complete.jpg)