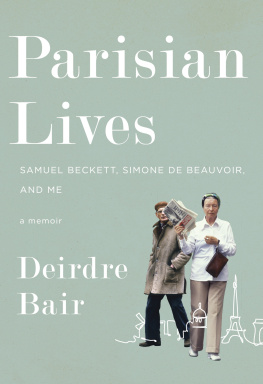

Copyright 2012 by Deirdre Bair

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Nan A. Talese / Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.nanatalese.com

DOUBLEDAY is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc. Nan A. Talese and the colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Book design by Pei Loi Koay

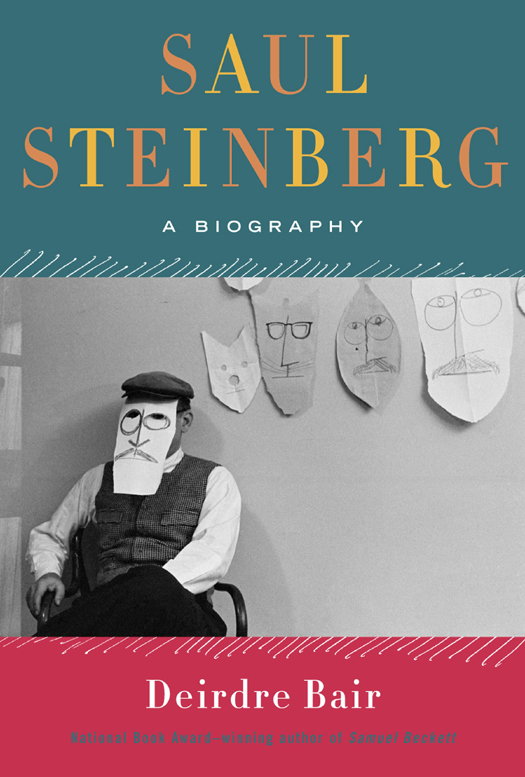

Cover art: Untitled (from the Mask Series with Saul Steinberg), 1962. Photograph by Inge Morath The Inge Morath Foundation/MAGNUM PHOTOS. Mask by Saul Steinberg The Saul Steinberg Foundation/ARS, NY

Cover design by Emily Mahon

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Bair, Deirdre.

Saul Steinberg: a biography / Deirdre Bair.First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Steinberg, Saul. 2. ArtistsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

N6537.S7B35 2012

741.092dc23

[B]

2011050601

eISBN: 978-0-385-53498-7

v3.1

For Aldo L. Bartolotta

(who never had a bad day)

I dont quite belong to the art, cartoon, or magazine world they just say the hell with him. They feel that he who has wings should lay eggs.

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

L ike many other Americans in the last half of the twentieth century, I grew up eagerly awaiting the arrival of The New Yorker each week. Back when there was no table of contents, I think a lot of people must have done as I did, flipping through the pages to scan the titles of articles and glance at the end to see who wrote them while reserving my initial attention for the drawings and cartoons. And from the quantity of fan mail the magazine received, I dont think I was the only one who stopped fanning the pages to study whatever Saul Steinberg contributed to an issue. His work always got my attention, and nine times out of ten, my first response was the same puzzled question: Just what did he mean by that? All those numbers, letters, squiggles, and curlicues; those funny animals and ferocious figures; the brutalist buildings, tranquil landscapes, and chaotic street sceneswhat was he getting at? And as for that poster, the iconic View of the World from 9th Avenue, dubbed by me and countless others The New Yorkers View of the World, I am sure I was among the first delighted buyers who rushed to the store on Madison Avenue for a copy, which has hung in every house Ive lived in since then.

When I became a university professor, my office bulletin board was festooned with Steinbergs covers, most of them the ones containing words that I used to try to inspire my students to think. There was the one that showed a man standing between two signs, one pointing to before and the other to after. There was the one with all versions of the verb to be, and the one that proclaimed I do, I have, and I am. And whenever assignments were due and I knew Id be deluged by requests for extensions, Id send my students a message by posting one of my favorite cartoons on the office door, of a man who sits behind a desk beaming as the word NO floats above his head and over to the deflated supplicant who sits in front of him.

In my home office, ever since I was a graduate student in Paris years ago and I went without lunches to buy it, a Steinberg print has hung on the wall where my eyes naturally gravitate when I raise them from my work. It has floated above every desk since the days when my ancient typewriter gave way to a succession of computers, because I always found something soothing in it during my daily search for whatever words or thoughts were eluding me. I still dont know what there is about this print, one of his landscapes from the era of The Passport, that is endlessly fascinating. It just is.

That vague generality pretty much characterized my overall response to Saul Steinbergs art until early 2007, when I saw two exhibitions of his work, at the Morgan Library and Museum and the Museum of the City of New York. I spent so much time studying the drawings and trying to puzzle out what inspired him to create them that the friends who were with me grew tired of waiting and were about to leave without me when I rushed to tell them how I thought Id found what Id been missing all those years. I had just read a caption that quoted Steinberg as having said, I am a writer who draws. That was it, of course, the elusive key that opened the first of the many doors that led me to spend three magical years searching for an understanding of his oeuvre.

On my way out of the Morgan Museum, I bought the book that accompanied the exhibition, and when I got home, I put it beside the four books of his drawings that were already on my library shelves. One by one I took them down again, once more finding puzzle and pleasure in equal part. Several months later, when I was packing books and files for a household move, I came across a huge folder left over from my teaching days that contained all the Steinbergiana that had adorned the walls and bulletin boards of my various offices. For the first time I was aware of the variety of his output, from New Yorker covers to product advertisements. I had saved an old Hallmark calendar and one leftover Christmas card from those he drew for the Museum of Modern Art. There was even a photo of a funny-looking fellow with a mustache and black-framed glasses holding a tiny brown paper mask over his nose, who I now knew was Saul Steinberg himself. How many years had I saved all this? It was hard to remember when I started, or even why. I knew nothing about the artists life when I collected all these things and until that moment had never considered finding out who he was, where he came from, or why he made such an impact on his culture and society. At that time I really believed that I would never write another biography, but thoughts about Saul Steinberg persisted, and almost before I could verbalize what they were, I knew that I wanted to write about him. One thing led to another, and that was the start of this biography. Four years later, the end result is here.

20072011

New Haven, Connecticut

CHAPTER 1

THE AMERICANIZATION OF SAUL STEINBERG

S aul Steinbergs Italian diploma in architecture stated clearly that he was of the Hebrew Race, which meant he was forbidden to work in Milan in 1940. He was a Romanian citizen, but his passport had been canceled, making him a stateless person bound to be rounded up by Mussolinis Fascist police and sent to an internment facility, the Italian version of a concentration camp. Although he was well known for his satirical drawings and cartoons in two of Milans leading humor newspapers, he lived for several months as a hunted man and never stayed long in any one place.

His Italian girlfriend hid him in her room and her friends hid him in theirs; his classmates from school did the same. But Milan was really a small town and difficult to hide in for long. It was only a matter of time until he would oversleep and be arrested in one of the daily 6 a.m. sweeps through the poorer parts of town, then be loaded onto a train with others who had run afoul of the Fascisti and sent to an internment facility. Those on the run heard rumors that suspects who surrendered voluntarily were treated better than those who were caught in the daily raids, and so, on the advice of his friends, Steinberg turned himself in at the neighborhood police station. Shortly after, he was indeed shipped off to an internment facility, Tortoreto.