This book made available by the Internet Archive.

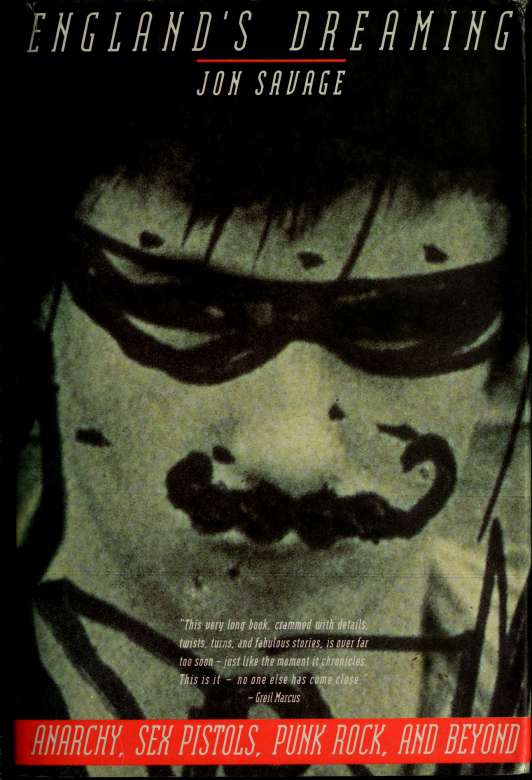

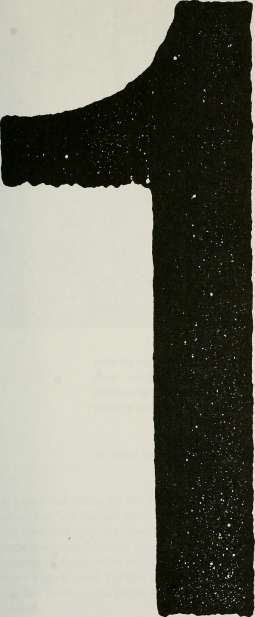

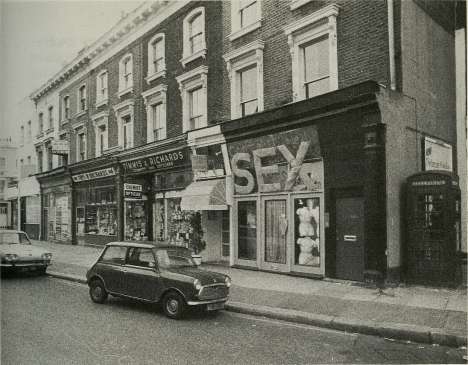

430 King's Road, London, October 1976 ( Bob Gruen)

In the city we can change our identities at will, as Dickens triumphantly proved over and over again in his fiction; its discontinuity favours both instant heroes and instant villains impartially. The gaudy, theatrical nature of city life tends constantly to melodrama.

Jonathan Raban: Soft City (1974)

We wander through London; who knows what we may find?

Lionel Bart: 'It's a Fine Life', from 0//Ver/(196O)

It is the early seventies. All the participants of what will be called Punk are alive, but few of them know each other. They will come together during 1976 and 1977 in a network of relationships as complicated as the rabbit-warren London slums of Dickens's novels. The other beginnings of Punk - the musical texts, vanguard manifestos, pulp fictions - already exist, but first we need the location, the vacant space where, like the buddleia on the still plentiful bombsites, these flowers can bloom.

That space is a small, oddly shaped shop at 430 King's Road, at World's End; the extended ground floor of a four-storey, late Victorian house, it was cheaply converted in the early years of the century. An iron pillar in the middle of the floor supports the roof. The only natural light comes from the front window. There is no inside toilet. It stands at a commanding position at the end of a row of similar, slightly larger shops; directly to the east is the local Conservative Association.

The building's changes of function illustrate the social shifts within this marginal area, a microcosm of what Malcolm McLaren has called 'the human architecture of the city'. The corner on which it stands is the first major deviation in the King's Road. World's End itself is named after a large pub that stands nearby. This name in turn derives not from the apocalypse but from the fact that, at the time when it was built, in the eighteenth century, it was the last house on the outskirts of the city, a boundary moving inexorably westwards from the World's End of Congreve, near Markham Square.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, this area of dead roads became associated with Cremorne Gardens, a stretch of land bounded by Lots Road in the south west and the World's End in the north east. Initially fashionable, the gardens degenerated, as public urban spaces will, into harbours of prostitution and low life of all types, and were closed in 1877. During the last two Victorian decades, World's End became a poor area, creating an atmosphere which, despite gen-trification, lingers in the World's End estate of seventies tower blocks.

After the First World War, 430 King's Road was occupied by Joseph Thorn, who carried on a pawnbroking business there for over thirty years. By the early 1950s, it had become a cafe, run by Mrs Ida Docker. The World's End was still a down-at-heel area belonging to the poor, the Bohemians, the transients of Pamela Hansford Johnson's 1937 novel World's End, whom Evelyn Waugh described (reviewing in Graham Greene's Night and Day magazine) as people 'economically, politically, socially, theologically, in a mess'.

As the upper reaches of the King's Road became fashionable in the mid-1950s, boutiques, coffee bars and other meeting places slowly spread down the street's eastern stretches. As a part of this process, number 430 ceased to be a shop that served only its immediate locality. For a time, it was a yacht agents, then the premises of a motor scooter dealer called Stanley G. Raper. In the winter of 1967, when Michael Rainey moved Hung On You from its previous site on Chelsea Green, it became chic.

Hung On You is a good example of the social mix that fuelled the synthesis of fashion, music and politics which has become London's principal export to the world. Along with David Mlinaric, Tara Browne (immortalized in the Beatles' 'A Day in the Life'), and Christopher Gibbs, Michael Rainey had been one of the original, aristocratic Chelsea stylists: an elite based, not on breeding or manners, but on pop values like style and glamour.

By the mid-1960s, the English music and culture industries were increasing exponentially - a process officially marked by the Beatles' investiture as MBEs in October 1965. Pop groups like the Beatles, the Animals and the Rolling Stones - with roots ranging from the suburban to the truly poor - were not only becoming rich and famous, but the new aristocracy: in John Lennon's phrase, 'the kings of the jungle'. They had few better role models than the Chelsea Dandies, whose taste for exotica was already well developed.

One can see the clothes on the Beatles or the Rolling Stones in early 1966: narrowly cut, high double-breasted suits in velvet or stripes, worn with garish, hand-painted forties ties, or thirties crepe-de-Chine scarves. This was the pop modernism of the mid-1960s on the cusp of hippie collage. As this style spread, it was principally sold in Carnaby Street or on the Portobello Road. Too remote, the World's End didn't directly profit from the bonanza. Although other shops like Granny Takes A Trip had opened in 1966, the corner was not a mass-market thoroughfare but a place for drugs, eccentricity or special pilgrimages.

Michael Rainey closed Hung On You early in 1969. He had helped to originate the idea of multiple identity in fashion - of clothes worn not in a uniformity of caste or taste, but in a riotous confusion of colours, eras and nationalities - but the next occupants of 430 took the idea of 'Fun Clothes' to a sickly conclusion. Trevor Miles had supplied Hung On You with kaftans; more recently, he had made waistcoats for Tommy Roberts' Kleptomania. They decided to set up a shop together, with a new name taken from an underground movie title.

Mr Freedom was like a gigantic playpen. Once inside the ice-cream-sundae, Deco frontage, customers were greeted by a giant stuffed gorilla dyed fun-fur blue. While a revolving silver globe in the ceiling gave an authentic Palais feel, they could buy jars of sweets from the counters with inset televisions twinkling away. Influenced by the 1950s, the clothes were trivial, garish and fantastic, pastiching the past thirty years of 'comic-strip, Hollywood vulgar'.