You see, theres something else Im going to do, something I must do only I dont know what it is. Thats why I go round painting and taping and drawing and writing and that, because it may be one of them. All I know is, this isnt it for me.

JOHN LENNON , interviewed by Maureen Cleave, How Does a Beatle Live? John Lennon Lives Like This, Evening Standard, 4 March 1966

In December 1966, an unusual multimedia magazine published its third issue. Created by former Womens Wear Daily editor Phyllis Johnson, Aspen was constructed as a sequence of stand-alone artefacts, each curated by a well-known artist or communicator and including anything from flexidiscs to Super 8 films, old newspapers and jigsaw puzzles. It was designed, in the vaunting spirit of the time, to break down the boundaries between disciplines, to transcend the bound-magazine format and, ultimately, to push through into another dimension.

The Fab issue was designed by Andy Warhol and David Dalton. The cover resembled a packet of detergent, and inside were plenty of inserts to wipe clean your mind: a Ten-Trip Ticket Book; a flip book with images from films by Jack Smith and Warhol; twelve postcard reproductions of pop art paintings; an Exploding Plastic Inevitable underground newspaper, with writing by John Wilcock, Jonas Mekas and several others; as well as a report on the recent Berkeley Conference on LSD.

One of the inserts was an A4 folder entitled Music, Man, Thats Where Its At, which contained essays by the Velvet Undergrounds Lou Reed, the sculptor Bob Chamberlain and Robert Shelton. All sought to describe the new condition of pop music in 1966. It was no longer simple commerce, teen romance or good times but something else: a total immersive experience, the popular form that, out of all the arts, truly reflected contemporary life. It was, in Reeds words, the only live, living thing.

Robert Shelton developed this theme in his essay, Orpheus Plugs In, which, by placing Bob Dylan at the forefront, discussed how poetry and poets were taking over the charts. The age of space is moving us outward, he began, the age of drugs is moving us inward. And the age of the new mass arts is moving us upward, inward, outward and forward. In this era of exploration, there are many breeds of navigators, but few more daring than the poet-musicians who are leading our pop music in new directions.

Where was pop music 20 years ago? he continued. Dinah Shore sang Buttons and Bows. Helen Forrest sang Ive Heard That Song Before. Kay Kyser played Ive Got Spurs That Jingle Jangle Jingle and Ole Buttermilk Sky. The level of our pop music has changed profoundly in 20 years, no in five years, from pop art to juke-box poetry. Todays music is talking about unvarnished reality, not about the fantasy that the commercial pop-song-writers were so deeply mired in.

Citing the fusion of music, poetry, dance, lights and film that could be experienced in the Avalon ballroom in San Francisco or at the Exploding Plastic Inevitable residency at the Dom in New York, Shelton called it a new, total art form. He concluded that the 1966 trend is shifting toward a non-political, non-society oriented philosophy as the songs speak of alienation and anti-convention. Paradoxically, they are expressing an avant-garde, underground philosophy to a mass audience, deepening the thinking of masses of young people.

One might expect Lou Reed to be rhapsodic about pops possibilities he was, after all, a young practitioner anxious to make his mark but Shelton was no youthquaker. Aged forty in late June 1966, he had served in the US Army during the Second World War. In 1955, he was among the thirty New York Times staffers subpoenaed by the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee during its investigations into Communist Party infiltration. When he refused to give evidence, he was given six months in prison, but the decision was reversed on appeal.

While his case passed back and forth through the courts, Shelton was reassigned from the news desk to entertainment. He began covering the late-1950s folk revival most notably the various Newport Folk Festivals and, in 1961, he wrote the first favourable review of a twenty-year-old singer, presenting him as an apprentice alchemist of time and space: thus launching Bob Dylans career. In March 1966, he conducted an extraordinary interview with Dylan high above the Earth, on a flight between Nebraska and Colorado.

Shelton wasnt the only one to remark on this flowering of mass art. Other experienced commentators like Nat Hentoff, Ralph Gleason, Kenneth Allsop, Reyner Banham and the sociologist Orlando Patterson all recognised that something extraordinary was happening in popular youth culture during 1966. Their fascinating and thoughtful observations were echoed, in a rawer and less distanced form, by the younger writers in the UK and US pop press: Richard Goldstein, Paul Williams, Tony Hall, Penny Valentine and many others.

It was a time of enormous ambition and serious engagement. Music was no longer commenting on life but had become indivisible from life. It had become the focus not just of youth consumerism but a way of seeing, the prism through which the world was interpreted. This isnt it for me: that simple, defiant cry, delivered by John Lennon, the most famous young person on the planet, echoed throughout 1966. Success wasnt the be-all and end-all; it was possible to conceive of an alternative future, to believe that things could be different, that people could be free.

1966 began in pop and ended with rock. Along with the increased ambition to be heard in the music, it was a year of rapid change and development in the various liberation movements: not just civil rights the engine of dissent in the mid-sixties but womens rights and the emerging homophile movement. It was also a year in which, triggered by the escalation of the war in Vietnam, the right wing began to organise and, indeed gain power. 1966 began in the Great Society and ended with the Republican Resurgence.

The folk memory of 1966 is contained in songs like These Boots Are Made for Walking, Sunny Afternoon, Reach Out Ill Be There, Yellow Submarine, Good Vibrations and so many others, powerful nostalgia triggers that hark back to what appears as a simpler, sunnier time. In Britain, there is the high point of England winning the World Cup and Swinging London, two national events that were revived thirty years later during the simulacrum of Cool Britannia.

Everyone thinks they know about the sixties. It was a golden pop age; it was the moment when everything started going downhill. It was the start of the alternative society; it was only a couple of hundred people in London, while real life whatever that is went on elsewhere. Even the clichs have become politicised: it should be noted that the sixties have been attacked by successive waves of cultural conservatives the New Right, the neo-cons and the neo-liberals over the past thirty years.

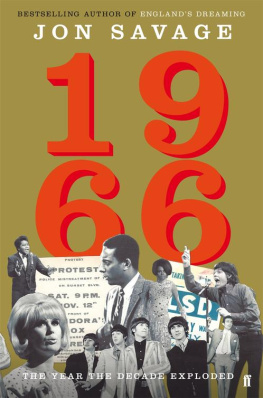

This book contains twelve essays, one per month, based on one record and then expanding out into the themes and events of that month in America and Britain. The choice of the single is deliberate: 1966 was the last year when the 45 was the principal pop music form, before the full advent of the album as a creative and a commercial force was heralded by