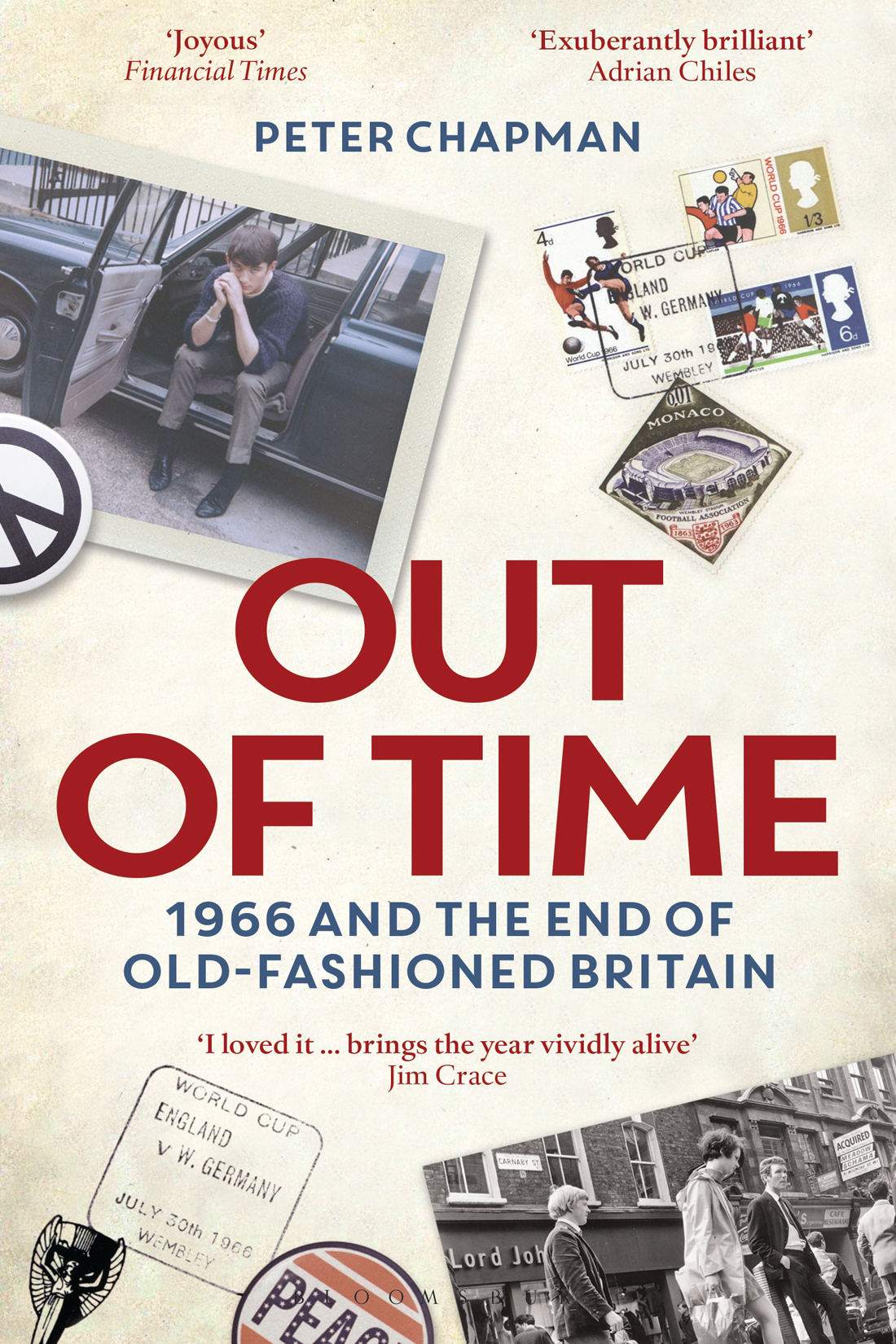

OUT OF TIME

A NOTE ON THE AUTHOR

Peter Chapman was brought up in Islington, north London. In the 1960s, he played in goal for Leyton Orient junior and colts teams. He was a correspondent for the BBC and The Guardian in Central America and Mexico from 1981 to 1986. He covered two World Cups Mexico 1986 and Italy 1990 for ITV and is now an editor and writer at the Financial Times, where he plays five-a-side football. He lives in Norwood, in south London, where the stolen World Cup trophy was found in March 1966 by a local dog, Pickles, out for his evening walk.

Also by the author:

The Goalkeepers History of Britain Jungle Capitalists (published in the US as Bananas: How the United Fruit Company Shaped the World) The Last of the Imperious Rich: Lehman Brothers 18442008

To Alexandra, my daughter, and Pepito,

my stepson, and to all the family.

And in memory of Doreen (19502015).

OUT OF TIME

1966 AND THE END OF OLD-FASHIONED BRITAIN

Peter Chapman

Contents

For much of the long afternoon we drove along the north coast of France and Belgium looking for a boat home. In Calais, where we had landed three weeks earlier, we were told we would be lucky to leave before the following day. When we reached Ostend we heard the same story except that we might do better to turn around and head back towards France.

In either direction we passed other vehicles engaged on the same mission. Some drivers had pulled over and parked haphazardly on the grass verges, possibly indicating panic. People stood at the roadside looking at a loss what to do, or studying their maps to review their chances of getting away. Several waved and gave us the thumbs-up in determined solidarity.

In the early evening a line of cranes came into view to our right a mile or so off the road, signalling hope with the approach of another port. It surprised me that this one was here at all. I had heard of it, of course, though had it more in mind as a place from ancient mythology than as somewhere that actually existed. This should be interesting, said my father, pointing at the sign into town. I wonder if anyone will rescue us from Dunkirk.

The date was Sunday 10 July 1966, my 18th birthday and the day before the World Cup started. We all had to be back in London the next day. My parents had their jobs to go to and my sister needed to attend the last few days of the summer term. She had been given the previous three weeks off school on the grounds that a continental holiday would be good for her education. I had to be back for my first day at work.

In Dunkirk harbour, no boats were at hand and none were on the horizon. A little distant from the quay were the masts, sticking out from the water, of some of the many craft that had come to evacuate the British army from Europe in the summer of 1940. Of that heroic fleet the little ships as we had heard them called that had carried out the rescue a quarter of a century or so before, they were among the many that had been sunk by the Germans and which had been left as a memorial to this formative moment of our island history.

Two lines of cars had formed near the ferry terminal, with about a hundred people gathered around. Most of them were silent or talking quietly among themselves. Some appeared weary and a few were shaking their heads. The most cheerful was a group of about 20 Germans, laughing and chatting, and oblivious to any historic reverence their location might have had. Before long, some German-speaking Swiss joined them. They were all coming over to England for the World Cup. Of the 16 national teams that had qualified for the final stages of the 1966 tournament, West Germany and Switzerland had been pulled out of the hat to play each other in one of the initial qualifying groups of four. They were to meet at Hillsborough, in Sheffield, in a couple of days time.

How we were all to make it across the Channel was uncertain. The seamens strike in Britain had begun in late May and raged for weeks. Nearly 900 ships and 27,000 merchant seamen had stopped work in the biggest strike the country had seen since the Second World War. Many boats had made their way from distant parts of the world: Aden, Hong Kong, and other points east of Suez. As they docked in their home ports, their crews had joined the dispute. Harold Wilsons Labour government had decreed a state of emergency. The army and the Royal Navy would be called on to maintain supplies of food to the outlying Scottish islands. The Royal Air Force would deliver the post to Northern Ireland; the province had troubles enough brewing without having to deal with a strike around its principal ports. Quite unrelated to the seamens protest, unrest had blown up again between the Protestant and Catholic communities, which had last been seen in the late 1950s.

Angry scenes in Liverpool, Britains second largest port after London and one of the most militant centres of the strike, had led to some of those few seamen who reported for work being thrown in the Mersey. You saw pictures of them having to swim their way out through the rivers oil and grime. The prime minister came to speak in the city only to be abused by crowds of strike supporters. He described the experience as not pleasant.

My familys response to the strike was to take no notice of it and carry on. My parents had in the 1950s visited the Continent about once every four years, unusual for people of our background. We would take the ferry from Dover and the international train down from Calais to Milan. We continued on by local train, in blazing heat and on wood-slatted seats, to Siena. This was to see friends my father had made during the war. As a Royal Signalman he had been part of the North Africa campaign and moved on to Sicily from where, over the years of the military advance through Italy, he had gone from the south to the far north of the country.

He had no background in language, and even in English had no formal idea what a verb or a noun was. Yet he had learned good Italian during the war. This was as well, since on our trips we rarely came across other British people. My mother, of north London Italian background two generations back, did not speak a word of the language but was the main instigator of our holidays. While she had no interest in, for example, the food other than the occasional sizeable lump of parmesan she was always curious about the ways of people abroad. Overall, she found them strange. I suspected one of the reasons she liked our holidays on the Continent was because they confirmed to her why we lived in England.

Since 1961, when my parents bought a car, we had gone every year. Initially their choice was a blue Ford Consul Classic, the model designed with a quirkily inward-sloping back window. Two years later my dad traded it in for a Ford Zephyr, in British racing green, as he pointed out. This had a no-nonsense appearance and looked a better candidate to take the weight of the roof rack and the several large suitcases loaded on to it for our foreign trips. The boot would be full of food, which my dad cooked up during roadside stops as we made our way across Europe. He used billy cans and a primus stove as if he were back in the army. In Italy in particular, where people did seem to stare a lot, car and lorry drivers slowed down to take in these weird goings-on at the roadside, to the great embarrassment of my sister and me. Our parents were oblivious.

On the outbound journey in 1966, we had used one of the foreign ferries that plied the Channel routes. While we were abroad, the seamens dispute had, in theory, been settled, although no sudden sense of urgency prompted by the imminence of the World Cup had led to agreement between the sides. Rather, Wilson had accused the seamens union leaders of being in the pocket of Communists manipulated by Moscow and, as an accompanying olive branch, promised an inquiry into the seamens grievances. The strike had officially been over for a number of days, therefore, by the time we came in search of a boat back to England, but this did not help matters. Some seamen had gone off to do other things during the stoppage and crews were difficult to muster. British ships and ferries remained, as a result, scattered around the coast with too few of them in the right place for normal schedules to resume. Hence, as my father headed in the direction of the Dunkirk port offices to find out what was happening and regardless of whether England were due to kick off against Uruguay the following evening in the World Cups opening game the evidence pointed to our being stuck.