England and the 1966 World Cup

England and the 1966 World Cup

A cultural history

JOHN HUGHSON

Manchester University Press

Copyright John Hughson 2016

The right of John Hughson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Altrincham Street, Manchester M1 7JA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for

ISBN 978 0 7190 9616 7

First published 2016

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Typeset by

Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire

Contents

Figures

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to many people for making various contributions related to this book over the last few years, including those who have shared personal memories of the 1966 World Cup Final. A number of colleagues have shared information and materials relevant to the book and in this regard I would like to thank Alan McDougall, Stacey Pope, Chris Stride and Jean Williams. Thank you also to Jean for giving me the opportunity to speak publicly on aspects of the research. A special thank you to Graham Deakin for the many conversations over the last couple of years relevant to the 1966 World Cup and for the insights from his designers eye. For their assistance in the research archive at the National Football Museum, I am especially grateful to Peter Holme and Alex Jackson. For comments on the manuscript and constant support, I am gladly indebted to Kevin Moore. Thanks to Tom Dark and Tony Mason at Manchester University Press for supporting the project. I am grateful for the funding made available to the International Football Institute at the University of Central Lancashire to assist research activity for the book. Finally, my heartfelt thanks to Marina Hughson. Marinas personal and professional support has been unstinting and invaluable on the long and winding road back to 1966.

1

This is England 66: an introduction

Let homage be rendered to the various sports, and in particular to football. For, still more than the king of sports, football is the king of games. (Jean Giraudoux)

English people of a certain age may well remember where they were when England won the World Cup on 30 July 1966. In each case the memory of seeing the World Cup Final, mostly on television, was recalled with such apparent vividness to confirm my belief, held from the outset, that this is a topic well worthy of thoroughgoing academic attention. Fifty years on, this may not be the only book by an academic published in 2016 on Englands World Cup victory, but it is likely to be the only one written by someone over the age of fifty-five who did not watch the match at the time. In July 1966 I was eight years old and, while the World Cup Final was being played at Wembley Stadium, I was asleep in my bed at home in the early hours of a western Sydney morning. Had I been able to watch the match, I may well have done so. Attending state schools with a significant number of fellow students from the diversity of European migrant communities residing in my neighbourhood, I developed an interest in the sport we referred to as soccer from a fairly young age. I have my own memories perhaps more hazy than vivid, but certain enough to remark upon of standing around in the schoolyard discussing the replays of either Match of the Day or The Big Match on local television. As it was only these broadcasts of football from abroad that we got to see on a weekly basis, for an Australian child, becoming a soccer fan meant developing a keen interest in the English League.

I have no memory of first hearing about England winning the World Cup in 1966. It just seems to have lodged within my awareness, at a formative stage, as an accepted fact of football history. This taken for granted understanding was accompanied by an assumption that winning the World Cup would involve a fairly uncomplicated response of national pride for English people. Facile views of this kind came under challenge once I took up studying sport seriously, However, rather than the primary interest here being in defending Ramseys image, it is in understanding how his caricaturing connects to criticism of the circumstances surrounding Englands winning of the World Cup in 1966. If there is a key protagonist in this book, then it is Ramsey. Criticisms of Englands World Cup victory are so closely tied to him that he demands more than the already considerable attention he would receive in a study of this topic. A central argument in my book is that criticism of Ramsey, for the style of football he had England play in the 1966 World Cup, fails to recognise that he was a modernist in a way not unrelated to art. His innovation to playing strategy has not been denied, but references to him modernising football tend to regard him as a ruthless technocrat devoid of aesthetic sensibility. The case presented here suggests otherwise and is intended to free Ramsey from an association with sterile scientific management.

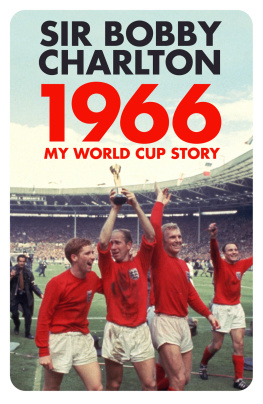

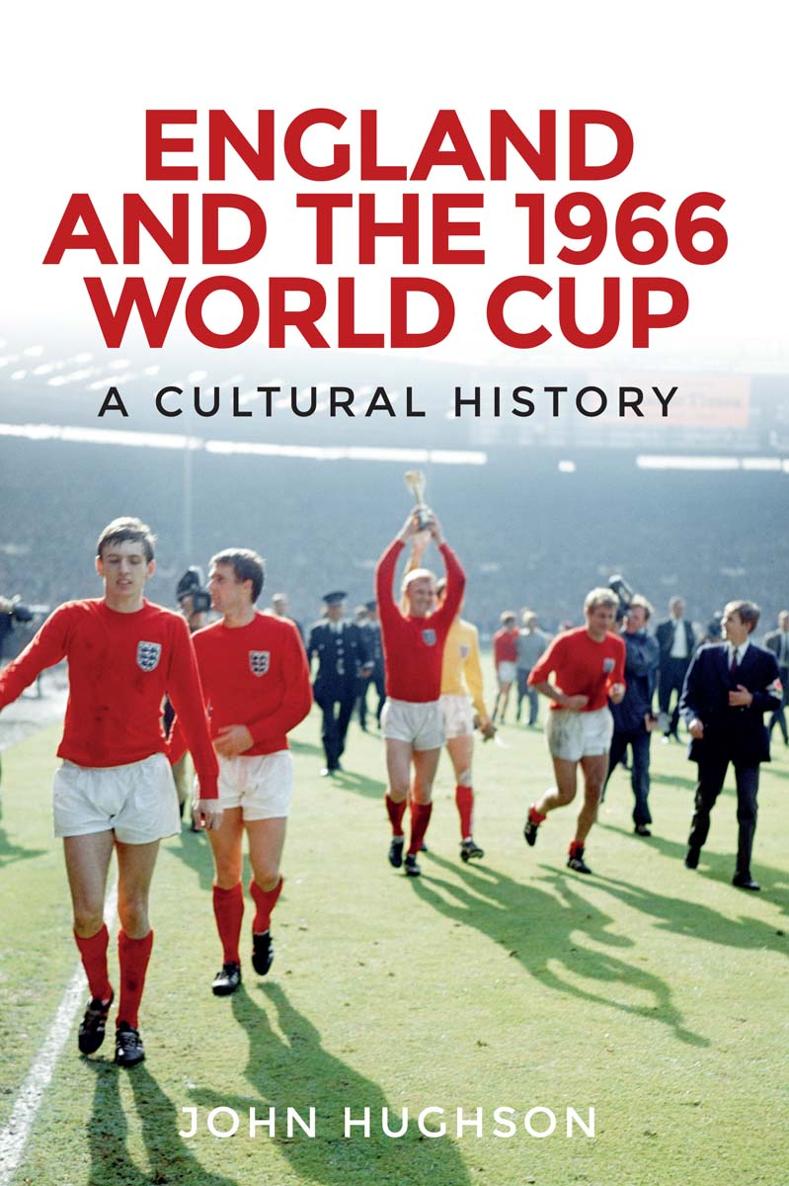

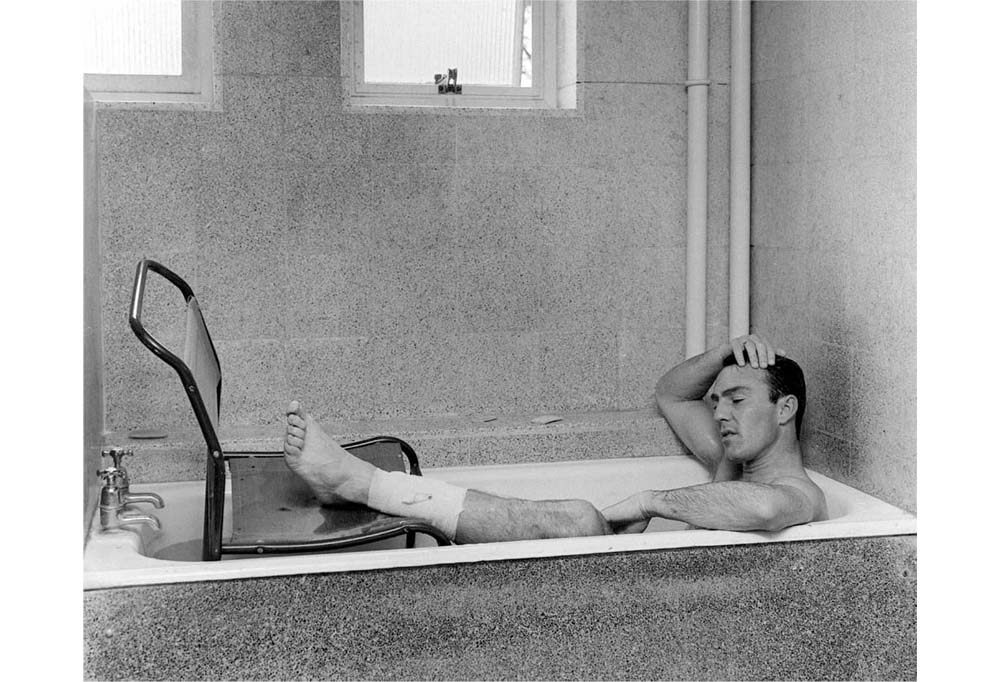

The one particular episode that supposedly highlights Ramseys lack of appreciation for the aesthetics of football is his exclusion of the virtuoso player Jimmy Greaves from the World Cup Final team. Ramseys treatment of Greaves offers an indictment that no critic of the England manager can miss. From the outset of the World Cup finals tournament Greaves looked an uncomfortable fit within the playing system Ramsey had developed. However, Greavess undeniable goal-scoring potential secured his selection in the England team for the three Group stage games. In the last of these games, against France, Greaves sustained a laceration to his left leg that put him on the injury list for at least the next game, the quarter-final against Argentina. A photograph shows a despondent and solitary Greaves in the bathtub after the match, his bandaged leg rested on a chair to elevate it above the water. Upon seeing this image I was reminded of Jacques-Louis Davids painting, The Death of Marat, in which the assassinated French revolutionary leader lies prone in his bathtub just seconds after taking his last breath.

1 A dejected Jimmy Greaves in the bathtub ponders the implications of his leg injury.

Ramsey did just this and, like the writers, architects, designers and artists Harris discusses, he too may be regarded as a romantic modern.

In a country where modernism has struggled to gain popular appeal especially in architecture it is not so surprising that the sharp-lined geometry of Ramseys playing system has had its critics. Remarks about the aesthetics of football being made via seemingly exclusive reference to a romanticised beautiful game, suggest little appreciation for the type of football that Ramsey fostered. Ramseys preoccupation with winning the World Cup has also been a sign, for some, of his lack in aesthetic vision. Yet I would argue that the unswerving ambition to win the tournament provided the framework within which his aesthetic vision was developed. Baudelaire predicted the modernist aesthetic in art when he wrote of the possibility of beauty residing in the essential quality of being the present. Ramsey understood this in relation to football. He did so because he understood the very nature of football as a modern activity, circumscribed by the present, in terms of seasons and tournaments. I argue that the playing system developed by Ramsey to win the 1966 World Cup was guided by an aesthetic awareness of related functionalist priority and that the result is comparable to a constructivist art project. This may present a challenge to more conventional ways of seeing football, but, for that, no apology should need to be made.