First published by Pitch Publishing, 2021

Pitch Publishing

A2 Yeoman Gate

Yeoman Way

Durrington

BN13 3QZ

www.pitchpublishing.co.uk

David Hartrick, 2021

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright.

Any oversight will be rectified in future editions at the earliest opportunity by the publisher.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the Publisher.

A CIP catalogue record is available for this book from the British Library

Print ISBN 9781785317811

eBook ISBN 9781785319471

--

eBook Conversion by www.eBookPartnership.com

Contents

To Seb.

Maybe next time

Gazza will score.

FOREWORD

by Daniel Storey, football writer

and broadcaster

ITALIA 90 produced my first football memories. Perhaps that makes me incredibly fortunate. As a four-year-old who was still a year away from my first season ticket but was already consuming football VHS tapes and watching Match of the Day at least three times every week, I was a willing test case. Never before had I enjoyed multiple live matches every day, nor even considered that it might be a possibility. Nor had I experienced football as a global entity, a festival of sport.

The brilliant aspect of establishing a love for football for anything at such a young age is that you latch on to the best bits without feeling the need to focus on anything that might not fit your enthusiasm. Innocence and inexperience allowed me to consume football without context. Hindsight and the passing of time provokes a series of glorious, blurry half-memories. As a Nottingham Forest supporter I was devastated by Stuart Pearces penalty miss and Englands exit, but it didnt wrap my enjoyment in a thick smog. How could it when there were two more matches to come?

But the context of Englands achievement did matter. It provides the backdrop for, and backbone of, David Hartricks book. He places Italia 90, the books crescendo, in the extraordinary circumstances that led to its unlikely reputation as English footballs Age of Enlightenment.

The 1980s was the darkest decade for our national sport, and David provides exemplary detail and discussion of hooliganism, the circulation war that provoked visceral newspaper criticism, the damaged reputation of English football and English football supporters and the public discontentment and national anger that led to it. Our footballing landscape had become synonymous with tragedy and disorganisation, our clubs were banned from European competition and the national teams support was viewed as a cast of unsavoury, unpleasant yobs.

If Italia 90 marked a sea change in the globalisation of football, perhaps the best marker of the game entering the modern age, it was also a landmark tournament for Englands national team. From the media diatribe and back-page scorn of the 1980s came hope of a new England team, one that could rise up to meet the challenges and pressures of a major tournament rather than crumple under them. The glorious summer of 1966 would never, and will never, be forgotten, but in terms of a lasting legacy and the weaving of individual storylines Italia 90 really did match up.

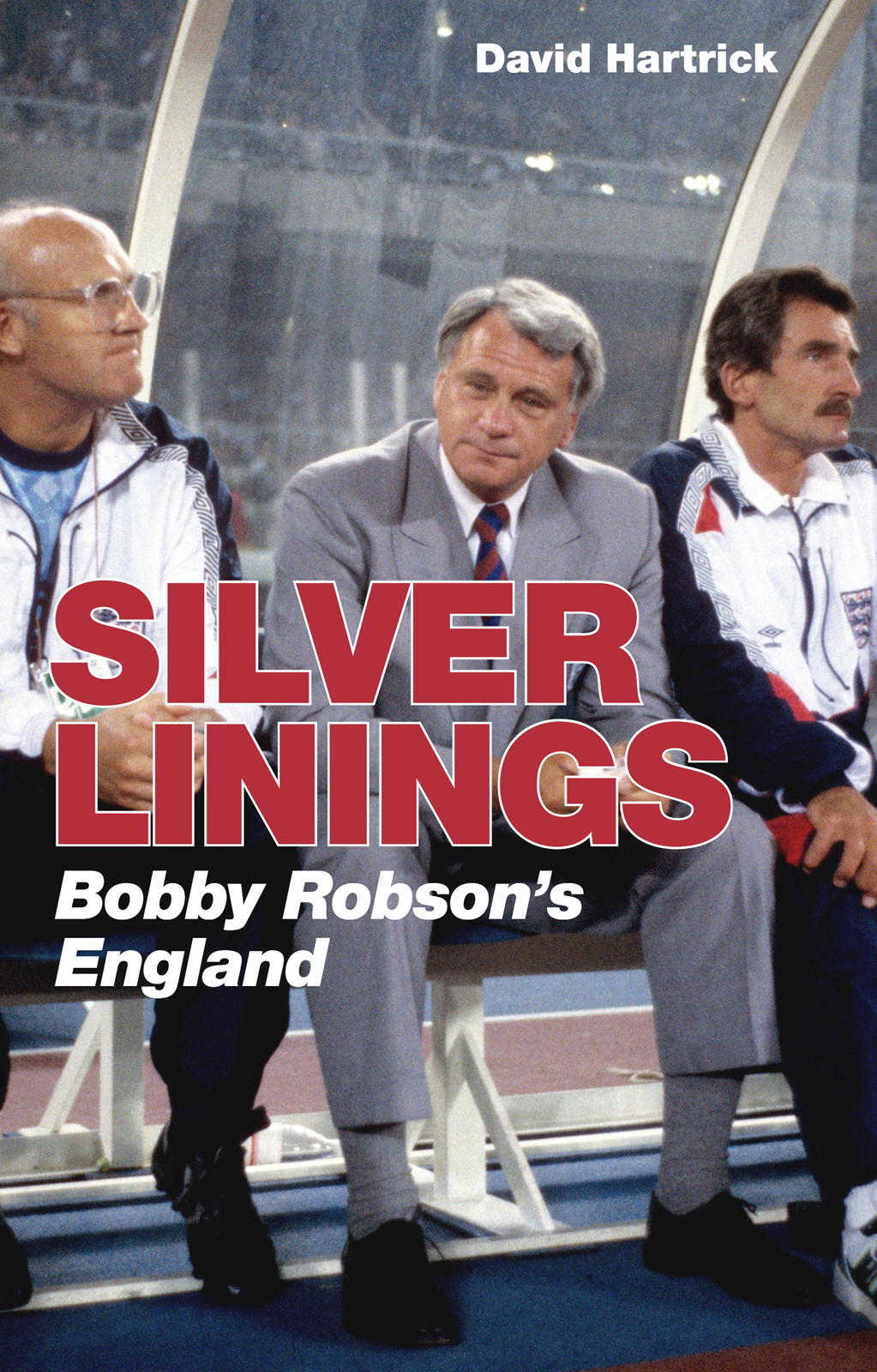

Bobby Robson is the protagonist of Hartricks book, Englands manager for eight years in the 1980s and a coach who constructed his own legacy at that World Cup. Robsons treatment at the hands of the tabloid media is examined in faultless detail. His struggle to establish England as a serious contender, through European Championship failure and World Cup infamy in 1986, passes comment on English football as a whole and Hartrick balances the micro and macro elements of the story expertly.

Robsons crowning glory, taking England to within two spot kicks of a second World Cup Final, is framed as a testament to the enduring optimism of the manager but also the eternal warmth, generosity and kindness of the man. There is a persuasive argument that no England manager has ever got more out of his players than Robson. From the penalty-box prowess of Gary Lineker, the natural aptitude of John Barnes and Chris Waddle, to the stereotypically English courage and passion of Pearce and Terry Butcher and the unique fragility of Paul Gascoigne, Robson proved himself capable of man-management through genuine friendship.

I have known David for a decade and am comfortable in asserting that I can think of no person better placed to document this period of English football. He is a devotee both of the England national team and the research required to detail its journey through such turbulent waters. He is unafraid to criticise where appropriate English footballs structure, hierarchy, the behaviour of supporters and the fear that once seemed to engulf the England team when it mattered most. Hartrick does not avoid scrutiny of the mistakes and the missteps.

But this is not purely a tale of woe, even if there are times during the book where hope feels like another countrys property. Without Mark Wrights winner, David Platts volley and Linekers penalties it surely would have been just another effigy to England failure. But Hartrick frames the stumbles, the roadblocks and the failures in the context of what we know the books denouement will bring: glorious public salvation and that open-top bus tour of Luton during which every player was adored as a hero rather than lambasted as a statue to continued non-fulfilment of potential.

ID cards, perimeter fencing, segregation, Diego Maradona, Allan Simonsen, Ray Houghton, Margaret Thatcher these could so easily have been the defining actors of England in the 1980s. But as the title alludes to, Silver Linings offers due recognition to them all while making a persuasive and illuminating argument that it was Robson who stepped forward as the defining individual and Gascoigne as a portent for the future, for better and occasionally and infamously worse.

PROLOGUE

Sunday, 8 July 1990

IT WAS never supposed to end like this. There should have been apologies and furtive looks to camera. A background of grey skies was meant to meet the hunched shoulders and bowed heads walking solemnly down a set of aircraft steps. A hundred newspaper columns were written and ready, each singing a joint chorus of I Told You So and Same Old England in perfect harmony.

Yet, here on the pavements, streets, walls and roofs of Luton on a beautifully sunny day, the scene could not have been more different. This team boring, poorly managed, not good enough according to the tabloids had found a way to tear up the script and write themselves a new one. In the process they had taken a nation with them and delivered something no one had seen in English football for a long time: hope.

Hope in a time of hooligans, fences and barbed wire. Hope in a time of ID cards, the Football Spectators Act and Maggies war cabinet. English football, a landscape awash with tragedy and disarray for over a decade, suddenly looked like it may yet be able to save itself