A revealing and thorough analysis of the man and his style

Observer

An intelligent book Lovejoy is one of the most astute and well-informed journalists around

Time Out

THE definitive biography of Sven

Daily Telegraph

Throws up plenty of treats

Boys Toys

A good story and a great read

Fitness First

A perceptive biography

Sunday Times

Plenty of detail on Sven

FourFourTwo

Lovejoy has set the standard for Eriksson biographies

When Saturday Comes

A fascinating story

The Bookseller

PROLOGUE

WHATS LOVE GOT TO DO WITH IT?

My advice to Sven is to quit his job, too. Those bastards at the FA want to destroy him. The knives are out.

FARIA ALAM , after resigning as personal assistant

to the Football Associations executive

director, David Davies, August 2004

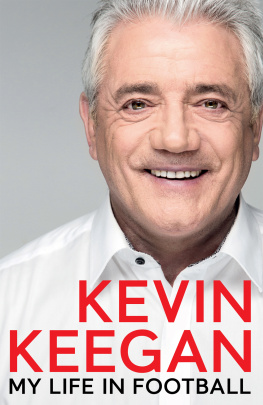

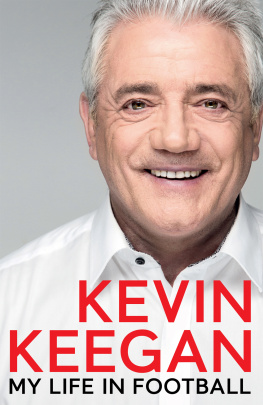

It was all a far cry from the heady days of November 2000, when Sven-Goran Eriksson was warmly greeted as Englands saviour on taking up the management at a time when Kevin Keegans abrupt departure had left the national team rock bottom, not just in their World Cup qualifying group, but mentally as well. Now, nearly four years on, the FA wanted him out, and were happy for it to be known that the best paid coach in the world was on borrowed time. If his employers were dissatisfied with Eriksson, the feeling was certainly mutual. He had been hung out to dry, as he put it, over the Fariagate sex scandal that had threatened to bring down the hierarchy of English footballs governing body, and briefly considered sueing for constructive dismissal before opting to soldier on until the next attractive job offer came along.

How had it come to this? It is a story that makes Footballers Wives look tame, a tale of unbridled lust, greed, intrigue and xenophobia, laced with a lot of football some good, some bad. When all is said and done, the final verdict has to be that Englands first foreign coach proved to be an expensive disappointment. He deserves credit for reviving the dispirited and disorganized team he inherited from Keegan, but having raised morale, performance and public expectation, he achieved no more than quarter-final places at the 2002 World Cup and 2004 European Championship when, with a more adventurous approach, England might have done much better.

In football terms, history will judge Eriksson to have been too defensively orientated, too inflexible in his team selection and tactics, and too indulgent of his players. In the big matches, England paid the ultimate price for timidly circling the wagons and defending slender leads instead of trying to improve them; they had no Plan B when bog standard 442 went awry; and, even for those patently out of form, it seemed harder to get out of the team than it was to get in it in the first place. This was most glaringly apparent in the case of David Beckham who, on his own admission, was not as fit as he should have been at Euro 2004, yet was invariably allowed to play the full 90 minutes, or even extra-time, when he should have been substituted.

One of Englands most experienced defenders propounds an interesting theory here. Remarking on a quote from Nancy DellOlio, Erikssons former partner, who told a TV chat show that he disliked one-on-one conflict, the player suggested this was evident both in the coachs personal and professional lives. The coach had remained with Ms DellOlio for at least a year after the relationship had run its course because breaking up would have been too confrontational, and he was reluctant to substitute senior players for the same reason.

Be that as it may, Eriksson often seemed to be in his captains thrall so much so that when the squad went to Sardinia in May 2004, for pre-tournament preparations, the coach and Nancy moved out of the best suite at the Forte Village, which they had been routinely allocated by the hotel management, to allow Beckham and his wife, Victoria, to move in. This sent out all the wrong signals, fuelling resentment within the squad of the special treatment, and unprecedented influence Beckham enjoyed.

Eriksson has always asked to be judged on results alone, in which case he was clearly overpaid on 4 million a year compared to the 1.1 million earned by Luis Felipe Scolari, who won the 2002 World Cup with Brazil and took Portugal to the final of Euro 2004. Given that disparity, it is unrealistic for the England coach to expect the media to focus entirely on football matters and ignore his private life. The intrusion Eriksson often complains about comes with the pay packet. As the Sunday Times put it, if he wants to be free to romance whoever and behave however he chooses, without it getting into the papers, let him go and manage Austria or Switzerland for 250,000 a year.

Initially, there was no shortage of sympathy when the stormy nature of Erikssons relationship with Ms DellOlio was made public, but gradually it dawned on people that for a man who craved anonymity he chose some strange partners, and strange venues at which to parade them. Not many women seek publicity as avidly as Ulrika Jonsson, and it surprised nobody but poor old Sven when she made a small fortune out of her kiss-and-tell tittle-tattle about their affair. Similarly, if you want to stay out of the newspapers, the celebrity haunt that is Londons San Lorenzo restaurant is hardly the best place to do your courting.

It was a close run thing at the time, but Eriksson got away with the Ulrika business. It was when others followed that public sympathy swung away from him, towards the much-put-upon Nancy, his live-in partner, who continually declared her love for him, and behaved accordingly, only to be repeatedly reduced to tears and tantrums by his serial unfaithfulness before they finally broke up, towards the end of July 2004.

Eriksson seems to enjoy risky, and risque, behaviour, and thought nothing of entering into a liaison dangereux with Faria Alam, a 38-year-old ex-model of Bangladeshi extraction who was employed on secretarial duties by his friend and most supportive ally at the FA, David Davies. Ms Alam had already had an affair with the FAs chief executive, Mark Palios, and when the newspapers got wind of what was going on, the inevitable furore became known as Fariagate.

Erikssons stock was already at an all-time low after Englands disappointing performance at Euro 2004, and at first it seemed he was behaving wisely straight after their elimination, when he retreated to his native Sweden and kept his head down. In fact he was seeking solace in the ample charms of his latest conquest, who had joined him at his palatial villa in Sunne, not far from his parents home. He had been seeing Ms Alam since January, and telephoned her every day during the championship in Portugal. Now they had another of their clandestine trysts, but this time the secret was out. The News of the World were on to them, and what followed was, according to one senior FA source, a glaring, startling nightmare that caused everybody to lose faith in the whole organization.

The crisis was provoked not so much by the affair as by Erikssons ambivalent reply when questioned about it by Davies that and the fact that Palios had also been involved with Ms Alam. Eriksson told Davies in a telephone conversation deemed by the coach to be personal and private that it was all nonsense. He was therefore both surprised and incensed when this brief chat with a friend led to a formal, public denial by the FA, which subsequently had to be retracted, causing great embarrassment to all concerned. The key word nonsense had referred to the fact that Erikssons love life was under scrutiny again; it was not a categorical denial that the relationship had taken place.

Next page