Contents

Guide

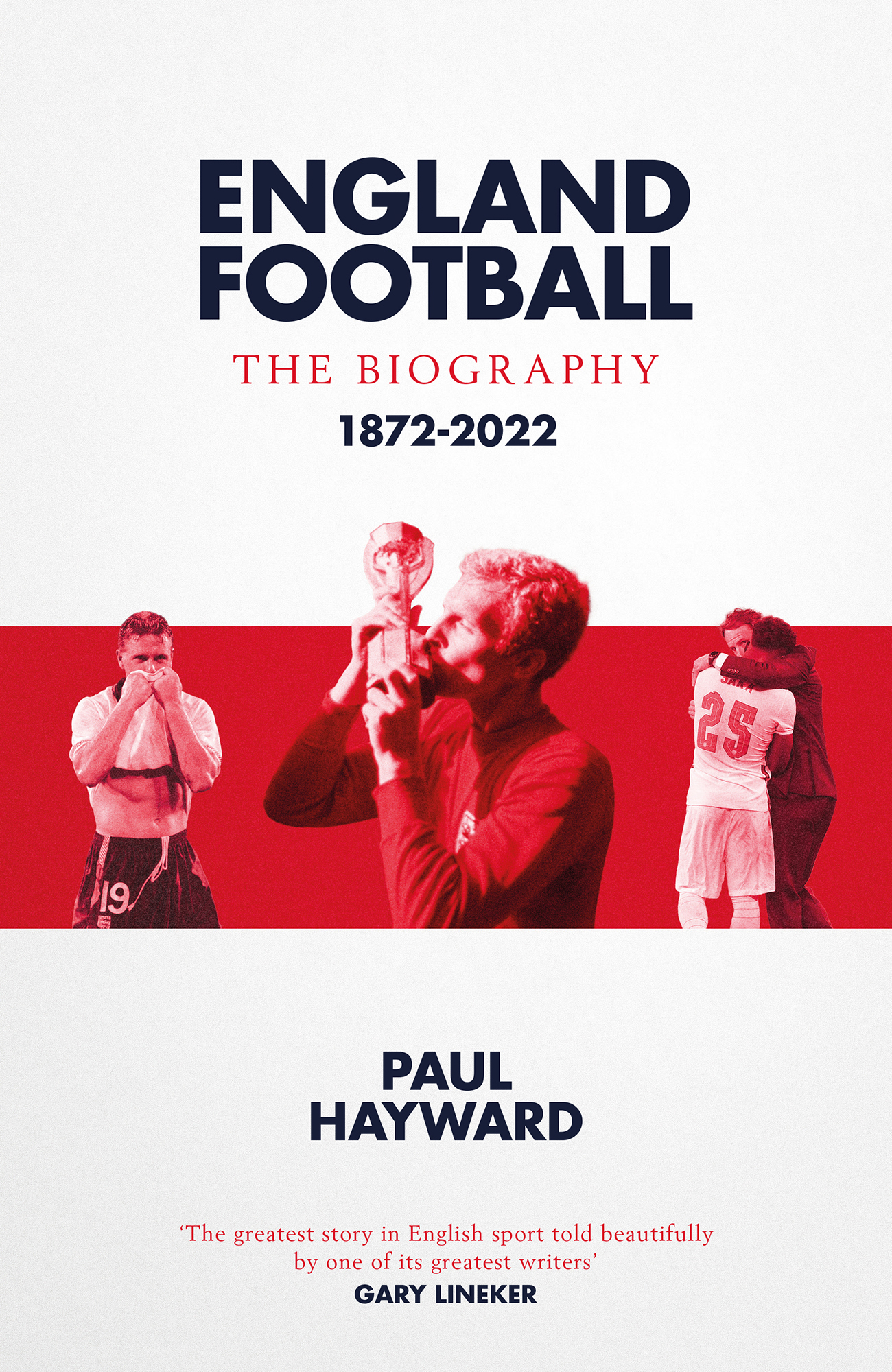

England Football

The Biography

1872-2022

Paul Hayward

The greatest story in English sport told beautifully by one of its greatest writers Gary Lineker

For Lewis and Martha

INTRODUCTION

Here, the intersection of the timeless moment

Is England and nowhere. Never and always.

T. S. Eliot, Little Gidding, Four Quartets

Harold Shepherdsons daughter, Linda Spraggon, returns with an old sports bag she had left the room to find and pulls out a blue tracksuit top and bottoms. The simplicity, beauty and meaning of the outfit reduce us to silence. Linda, her husband Frank and I consider the blue fabric, red and white piping and gold wire on the three lions badge. This is the tracksuit Shepherdson wore at Wembley as Alf Ramseys No. 2 when England won their only major international trophy the 1966 World Cup. The vibrancy and symbolism of the garment make us smile, and pause, and wonder where all the time went.

Fifty-five years later, with only Geoff Hurst from the 1966 side to bear witness, England were back in a tournament final at Wembley, the climax of the Covid-delayed Euro 2020. Defeat to Italy by penalty shoot-out followed a violent stadium invasion by hundreds of ticketless England fans and preceded a miasma of racial abuse for the three black England players who missed their penalty kicks. But in the days that followed there was a countervailing swell of support for Marcus Rashford, Jadon Sancho and Bukayo Saka, and a sense that the England mens team was blessed with promise.

Some, as Sakas penalty was saved and Italy rejoiced, may have felt, here we go again, a refrain of Englands story. But that wasnt the prevailing emotion. There was no rage, no deplorable scenes in Trafalgar Square. A justified tactical debate, yes; but relief too that England were now contenders again, with beacon players and a statesman manager. A manager who, in November 2019, articulated Englands dilemma: The win in the 1966 World Cup is the outlier, whereas, in actual fact, historically, we looked at it as the benchmark.

The outlier Gareth Southgate speaks of recurs in this book. Englands wait for a second trophy is one of the great itches and anomalies of world sport.

Some reassurance. This biography is not a tale of woe. There is woe in it and many inquests but the story of English sports most consuming quest is better than that. When Mohamed Salah won the Football Writers Association Footballer of the Year award in 2018, his manager at Liverpool, Jrgen Klopp, told the audience: You are blessed in this country with wonderfully talented, skilful, honest, committed and tactically astute players. Youre blessed with a coach [Gareth Southgate] who is brave and innovative. England has the tools because the manager and the players have the mentality, attitude and character. It is all there for you.

And some more good news. Every fault and failing in Englands long struggle is curable. None is congenital or inescapable. There is no virus in the system.

These pages focus only on the mens senior team, which has a history separate, for most of those 150 years, from the womens England side, and other representative England teams stories that deserve their own telling.

Its a 150-year biography not a chronology of a team who first stepped out on a cricket pitch in Partick, Glasgow, to face Scotland on 30 November 1872. Those mutually noisy neighbours conceived not only footballs founding rivalry but international football itself.

For a century and a half in this volume, the growth of the noxious weed as rugby folk called it advances from home internationals to football as the global game, the trauma of the First World War, isolationism, the political challenges of the 1930s, twentieth-century FA blazerdom, the great street footballers and Englands wide-eyed debut at the 1950 World Cup, through the Munich air disaster to Alf Ramseys golden age, and on to the wasteland of the 1970s, the stop-go cycle of the 1980s and 90s, diversity and race as vital drivers of the England team, then on to the punts on Sven-Gran Eriksson and Fabio Capello, stopping to draw breath with Roy Hodgson, before Gareth Southgate and the tournament revival of 2018-21.

Asked to sum up his England career, Wayne Rooney gave this poetic answer: Close. Good. Frustrating. The 55 years of Hurst, as the footballer writer Richard Jolly jokingly called it on Twitter during Euro 2020, are burned into the hearts of many illustrious England footballers and several baffled managers.

Since 1966, heavy labels have been tied to the England story: false dawns, near-misses, sackings, requiems, reviews, penalty shoot-out calamities and hope, promise and potential. The last thing the story needs is more generic tags. The intention here is to contextualise, reinterpret and most of all understand: to connect the threads from Glasgow in 1872 to Qatar, 2022.

An authors note: I covered the England mens side at the World Cups of 1998, 2002, 2006, 2010, 2014 and 2018, and the European Championships of 1996, 2000, 2004, 2012, 2016 and 2020, as well as in countless qualifying matches and friendlies at home and abroad. Where I refer in these pages to the press, I include, where applicable, myself. No distancing is intended. As a journalist I had reported on English and British success in every major sport, but not international football until the England womens team success at Euro 2022, fifty-six years on from 1966. That win invited the mens side to respond.

In the hiatus from 1966 to now, France emerged to become world and European champions in 1998-2000, and World Cup winners again in 2018. From 2008-12, Spain won the European Championship, World Cup and European Championship again. Since their defeat at Wembley in 1966, Germany have won three World Cups and three European titles. At Euro 2016, Portugal won an international tournament for the first time.

England, with its Premier League plutocracy of billionaires, oligarchs and sovereign wealth funds, has had to endure this pageant of near neighbours raising trophies and waving to the crowd. But the gap is finally closing between club power and the potency of the England team, which has abandoned the blunt, island-race parochialism of what can broadly be called 4-4-2 to embrace the world mainstream of possession- and skills-based play. Once, in my presence, a famous Brazilian coach was asked to describe the English style. He raised his hand to suggest a missile flying overhead while making a falling bomb sound. Nobody would characterise English football that way now. Tony Adams saw it, at Euro 96. Before that championship Adams said: People have thought, the English yeah, all heart, no brains.

This book started with a trip to a Glasgow library to find press cuttings for that first England game, in November 1872. And there they were, on ochre microfiches packed with narrow single columns and typefaces so dense that magnifying glasses must have been a fixture at Victorian breakfast tables. Straight away I was consumed by the chance to immerse myself in a story thats indivisible from English life, yet rarely analysed as a continuum, with connecting themes and strands. From a daunting mass of information, my aim was distillation, to find the essence. The fundamentals of journalism apply in all writing of this kind: the who, the when, the how, and, most importantly in this context, the why.

In the early autumn of 2020, I escaped the Covid cave to tour England and Scotland, visiting people involved in the England story and stopping off in significant locations to summon the mood or spirit of a time. I called in on the marvellous Linda Spraggon, and moved on to Middlesbroughs South Bank, the forbidding industrial landscape that Wilf Mannion escaped but then returned to, after football, as a fitters mate in a grimy boiler suit.