Contents

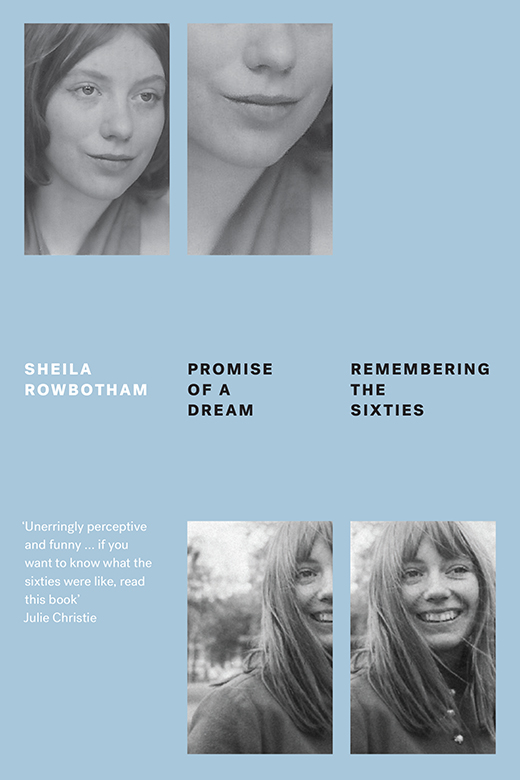

Promise of a Dream

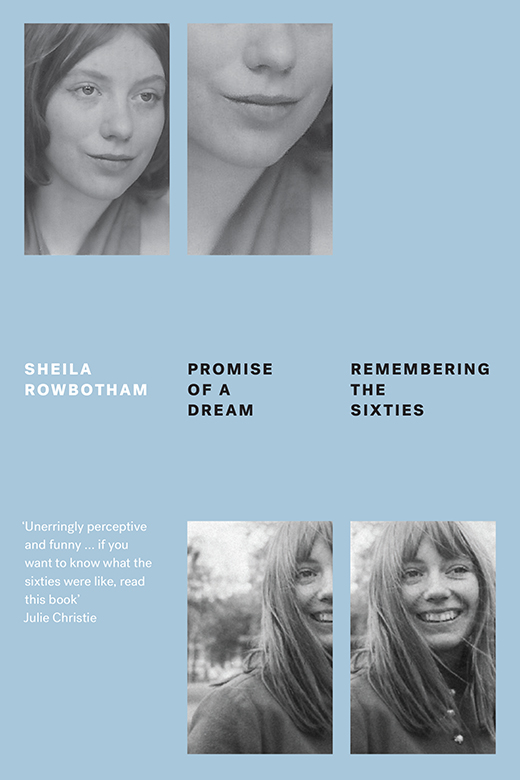

SHEILA ROWBOTHAM

Promise of

a Dream

Remembering the Sixties

This edition first published by Verso 2019

First published in the United States by Verso 2001

First published by Allen Lane The Penguin Press 2000

Sheila Rowbotham 2000, 2001, 2019

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-480-6

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-482-0 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-481-3 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Linotype Sabon

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Contents

All photographs are supplied by the author unless indicated otherwise. Every effort has been made to contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be glad to make good in future editions any errors or omissions brought to their attention.

My thanks go to Tariq Ali and Richard Neville, who inadvertently sparked off this book. In an unusual coalition, they got me on to a Radio 3 programme about the sixties which provoked the idea of writing down my story. Nikos Papastergiadiss interest in the artistic movements of the decade inspired the realization that I could take a new slant on my own memories, while Mike Savage reminded me of Walter Benjamins metaphorical labyrinth where all kinds of lost dreams, hopes and artefacts, swept aside by more recent fashions and developments, resided. The image became my standard as I wrote and rewrote.

My agent, Faith Evans, encouraged me to begin writing and was constantly supportive as I meandered through version after version. She gave me detailed editorial comments on the first draft I considered finished, combining much-needed firm criticisms with reassurance. Her skill and experience have been crucial factors in enabling me to find my way through an unfamiliar form of writing and I owe her a great debt.

I am similarly grateful to Tariq Ali, Vinay Chand, Barbara Davy, Monica Henriquez, Roberta Hunter Henderson, Tony Kaye, Marsha Rowe, Lynne Segal, Hilary Wainwright and Susan Watkins, who from the outset communicated a cheering faith, regardless of the lack of palpable evidence, in my capacity to write personal history. Their belief in me and in the value of doing Promise of a Dream was more vital to its completion than any of them realized. Along with Sally Alexander, Robin Blackburn, Nigel Fountain, Tony Garnett, Lindsay Harford, Hermione Harris, Jane Harris, Adam Hart, John Hoyland, Alison Light and Roger Smith, they also gave their time when I pestered them for facts and dates. Thank you to Stuart Hall, Hermione Harris and John Hoyland for photos and posters from their private collections and, for permission to reproduce their work, Red Saunders, Irving Teitelbaum and Arnold Cragg, who took the picture used for the cover. Ros Baxandall, John and Joan Bohanna, Barbara Davy, Stephanie Hunt and Hilary Wainwright all read parts of the manuscript at various stages and gave helpful comments. Monica Henriquez also read an early version with the graphic eye of a film editor and, with a few deft and imaginative suggestions, made me understand how to begin and how to connect crucial bits of the text. She made explicit for me what was buried and implicit.

The late Marc Karlins enthusiasm for my return to discarded memory sites was inestimably precious. Before he died in January 1999, he was beginning to make a film about radical history which was to include the writing of Promise of a Dream. We had time only for a preliminary discussion. As I completed the manuscript for the last time my thoughts were with him in a continuing unanswered conversation.

I am grateful to Dorothy Thompson for permission to quote from two letters of another friend, the late Edward Thompson, whose astute criticisms and generous-hearted praise in a succession of missives over three decades educated and sustained me.

I received wonderful help and support from my editor at Penguin, Margaret Bluman. Like my copy-editor, Lesley Levene, she responds with zest and an ebullient commitment well beyond any call of duty. Both have that great and miraculous gift of making a writer feel wanted and are a delight to work with.

Some of the material which went into Promise of a Dream was rehearsed in talks: the day event on radical film If Only , organized by the British Cinema and Television Research Group from De Montfort University in Leicester, Kent Universitys Conference on 1968 and a seminar for Manchester University history graduates. Thanks to the participants for the feedback they gave me.

A Guinness advert fascinated me as a child. Dont look now but I think were about to be swallowed, one drink declared to the other, an uneasy grin on its frothy cream head. I can recognize its discomfort now. Like many people who have lived through the sixties, I feel that my memories of what happened then have been swallowed several times over. This disjuncture between memory and interpretation is not only an inevitable consequence of time passing. It has arisen because, as the hopeful radical promise of the sixties became stranded, it was variously dismissed as ridiculous, sinister, impossibly utopian, earnest or immature. The punks despised the sixties as soppy, the Thatcherite right maintained they were rotten, the nineties consensus was to dismiss them as ingenuous. Dreams have gone out of fashion, making a decade when they were very real appear incongruous and elusive.

Then, even as the political and social radicalism of the era was being buried deep under the waste deposits of Conservatism, sixties pop culture was sent off to rehab. A sanitized sixties were to re-emerge, glossily packaged as the snap, crackle and pop fun time, to be opened up periodically for selective nostalgic peeps on cue: the pill, the miniskirt, the Beatles, Swinging London, Revolution in the Streets. As if anything was ever so simple!

Alternately reviled and idealized, the sixties remain the controversial decade you are expected to see as all good or all bad. By wrenching aspects of experience out of context, this dichotomy inevitably distorts and so this is a book that refuses to be either for or against.

By writing my own story of the sixties, I want to evoke what it felt like at the time, situate responses and relate my subjective take on events to a wider social picture. Of course a personal narrative is by definition partial, but it can also introduce unexpected slants by looking at what occurred from a point of view which has not previously been taken. The return to a specific source can move the angle of vision, skew the existing record and lay a new trail.

Sixties radicalism has become retrospectively incomprehensible because the framework of assumption has been so thoroughly eclipsed and because the record has been so often filtered through sneers or a bluff historical patronage. These derisory stances cannot adequately explain why thousands of us marched in protest against nuclear weapons or the American governments bombing in Vietnam. They have been unable to either comprehend our motives or communicate what we feared or opposed.