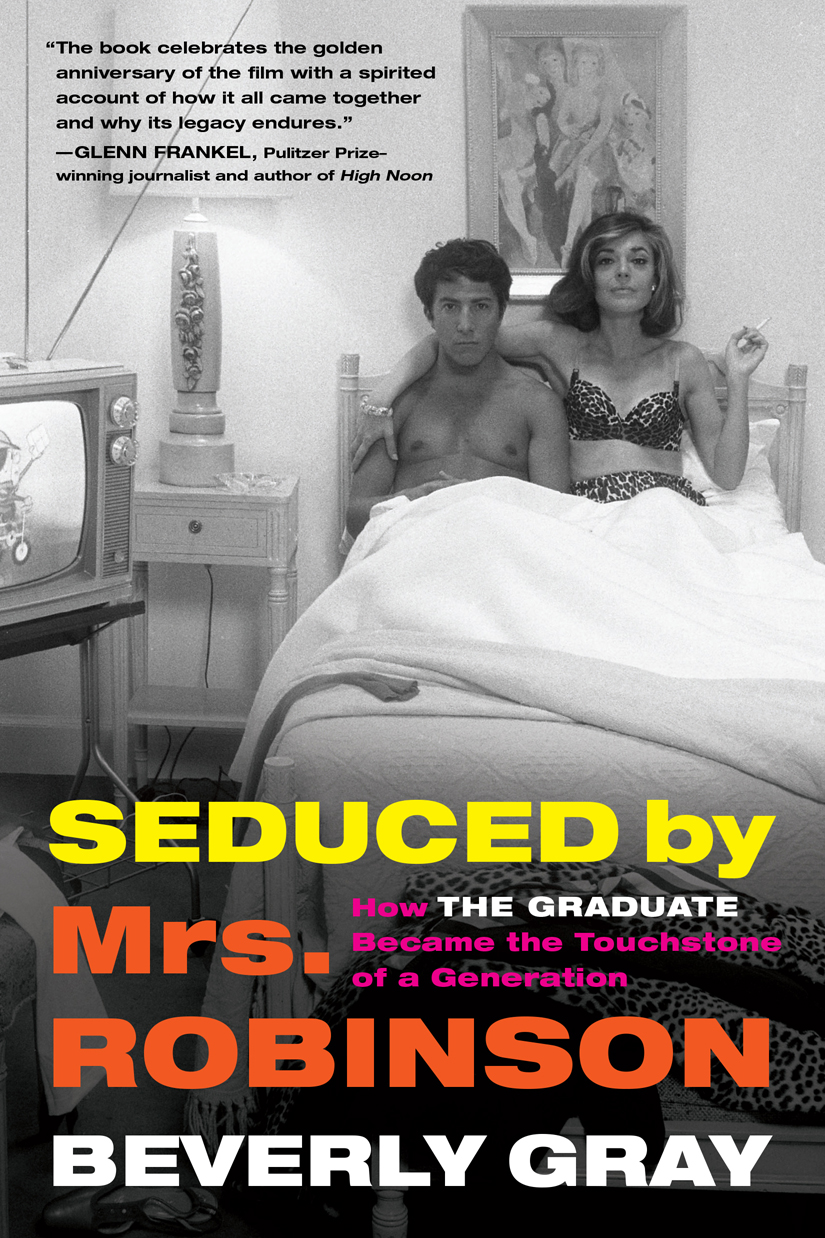

SEDUCED by Mrs. ROBINSON

How The Graduate Became the Touchstone of a Generation

Beverly Gray

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL 2017

Also by Beverly Gray

Ron Howard: From Mayberry to the Moon... and Beyond

Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers

Benjamin Braddock, played by Dustin Hoffman, is filmed arriving at Los Angeles International Airport. For decades the moving walkway and white tile wall were familiar sights to travelers at LAXs United Airlines terminal.

To the memory of

Estelle and David Gray

for shaping my past

To

Adrian and Mila Grayver

for enlivening my future

Contents

An Invitation

Theres this party. A young man, impeccably groomed, descends a staircase in a nouveau riche Beverly Hills home. Hes instantly accosted by a bevy of squealing suburbanitesthe female contingent of his parents circle of friendstricked out in sequins, feathers, and pearls. Liquor is flowing; tongues are wagging; everyone is keen to congratulate Benjamin Braddock on the honors hes racked up at an ivy-covered East Coast college. Whats next for the prodigy? Out by the swimming pool, one no-bullshit businessman with a twinkle in his eye insists hes got the answer:

Plastics.

But theres also a woman, with all-knowing dark eyes, who peels away from the others of her generation. She gives Ben the once-over, flicks her cigarette ash, and asks for a ride home. Though her intentions are not at first crystal clear, shes proposing a party of another sort. Thats how this graduate comes to get a very different education, in a film that plays off adulthood against youth, pragmatism against idealism, lust against love, cocktails for two against a connubial champagne toast. The Braddock homecoming soiree is where it all begins. (Only to end, of course, when Benjamin turns wedding crasher, disrupts a young womans nuptials, and runs off with the bride. Which puts a real damper on the wedding reception.)

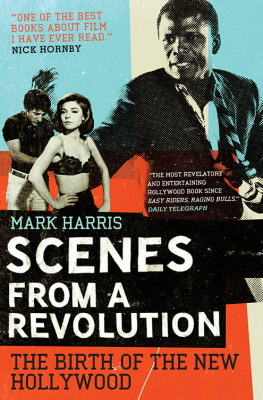

The whole world showed up at that party. The Graduate was intended as a small, sexy comedy based on an obscure novel by a first-time author. Neither its producer nor its director was a member of Hollywoods inner circle. Its cast was led by a short, big-nosed New York actor who, in the eyes of the eras pundits, looked nothing like a leading man. No major studio provided financing; it came instead from a low-rent entrepreneur best known for importing Hercules and other Italian-made schlock epics. But when The Graduate hit theaters in late December of 1967, moviegoers instantly took notice.

Once The Graduate burst onto Americas movie screens, Hollywood insiders were thunderstruck by the audience reaction. Young people clapped and cheered; their elders flocked to see for themselves what their offspring found so provocative. Soon intellectuals, religious leaders, and even politicians were weighing in, trying to use The Graduate as a key to understanding those unruly postWorld War II children who were now coming of age in large numbers.

I was one of them, a Baby Boomer with a lot on my mind. When The Graduate first touched down in Los Angeles, I was a college senior at UCLA. Longing to broaden my horizons, I had cajoled my family into letting me spend my junior year at a small university outside of Tokyo. It was a year of independence and adventure: I was speaking a foreign language and learning to adapt to very different cultural norms. But when I returned, in the early fall of 1967, to the land of the smoggy palm, I reentered the realm of my parents. Proud of my academic achievements, they hovered over me, intent on helping to shape my future. Did I really want to earn a PhD in English? Had I thought about law school? And shouldnt I focus on the possibility of getting married?

No wonder The Graduate struck a chord. Though I had always loved movies, I had inherited my tastes (like so much else) from my father and mother. They favored lavish musicals, wacky comedies, and serious postwar dramas (like The Best Years of Our Lives and Gentlemans Agreement) that reflected their own social values. When I was small, those were the movies I got to stay up and watch on late-night television, and I took them to heart. In the fifties, both The Wild One and Rebel Without a Cause passed me by, partly because I was far too young to connect with them, but also because I was too secure to identify with angry social outcasts. Though in later years I would end up working on a slew of low-budget genre features for B-movie maven Roger Corman, I was never attracted to Cormans seminal sixties youth flicks, like The Wild Angels and The Trip. To be honest, I had no cause to be a rebel.

But once Id moved back into my pink childhood bedroom, with its stuffed animals and a little sister too close for comfort, I paid rapt attention to the galvanizing movies coming to town. (Anything to get out of the house.) The turbulent year 1967 turned out to be a high-water mark for new American cinema, for films that took a hard look at the nation of my birth. Who could forget Cool Hand Luke? In Cold Blood? Arthur Penns Bonnie and Clydewith its exquisitely calibrated take on violence, American-styleseemed particularly timely, and particularly dazzling. Nonetheless, I hardly saw myself as a natural heir to outlaws like Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow.

The Graduate, though, was another matter. That polite young high achiever, those loving but smothering parents, those comfortable but slightly bland surroundings: They combined to form an only slightly exaggerated version of my own cozy West L.A. world. (Yes, we even had a swimming pool.)

Hey, wasnt that me up there on the screen?

THE SIX TIES WERE romanticized by those who came later, but for me it was a time of struggling to cope with a social landscape over which I had no control. Television plopped the big news of the day right into my lap. At the start of the decade, my classmates and I had watched on TV a handsome new president urging us to consider what we could do for our country. Suddenly, on November 22, 1963, he was dead. In the halls of Alexander Hamilton High School, students and teachers cried together. As we obsessed over the reruns of Oswalds slaying, followed by Kennedys funeral procession with its riderless black horse and its sad little boy, youthful idealists were rapidly turning into cynics.

We good-hearted Hamiltonians had been idealistic about the Civil Rights movement too. But the peaceful protests of the mid-1950s were now quickly evolving into violent clashes that left many of us feeling all too vulnerable. The TV sets in our rumpus rooms brought us the bad news in living color. Late in the long hot summer of 1965, just as my family was returning from a cross-country driving trip in a big-finned 59 Buick, parts of L.A. went up in flames. (History calls it the Watts Riots.) By 1967, we saw inner-city Newark being torched, and then Detroit. No one could guess where public anger would explode next. Meanwhile, the Vietnam War had escalated to the point where almost all the young males I knew were looking over their shoulders and concocting desperate schemes to avoid the military draft. Walter Cronkite revealed, on a nightly basis, the bloodshed and the body count. Hell no, they didnt want to go.

![Ruta SHepetis - Ashes in the Snow [aka Between Shades of Gray]](/uploads/posts/book/861085/thumbs/ruta-shepetis-ashes-in-the-snow-aka-between.jpg)