Copyright 2014 by Judy Chicago

All rights reserved.

Photographs 2014 by Donald Woodman unless otherwise noted.

Pages : Reproduced with permission of The Estate of Dame Laura Knight DBE RA 2013. All Rights Reserved.

ISBN 978-1-58093-396-4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013952209

Design: Gina Rossi

www.monacellipress.com

Introduction

Art has been the focus of my life. I began drawing before I talked, and I started attending art classes at the Art Institute of Chicago when I was five years old. My parents were political radicals, at least my father was; I always suspected that my mother went along with his program. When she was young, she wanted to be a Martha Grahamtype modern dancer. However, observing my grandmother walking home from work in the snow in order to save the penny required for a bus ride changed my mothers plans. She dropped out of high school in order to get a job and help support her family. But she always maintained an interest in the arts, making sure that I could go to art school despite my parents modest income.

My familys aspirations for my younger brother, Ben, and me involved encouraging us to make a difference, a notion that seems almost inconceivable in todays money-driven climate. But my mother and father, children of the Depression, were caught up in the revolutionary politics that persuaded many intellectuals to think, wrongly, that the adoption of Soviet-style Communism would transform a world full of injustices into some type of utopia with equality for all.

Ben and I were geared toward highly idealistic goals so idealistic, in fact, that neither of us had a proverbial pot to piss in for most of our lives, although my brother was able to provide a home for his own family shortly before his premature death of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Lou Gehrigs disease at age forty-seven. My childhood had been full of death, which made me acutely aware of my mortality. One cousin died during World War II, not from battle wounds but by falling into an open manhole as he was disembarking from his ship. When I was nine, a paternal uncle died from the same horrible disease that would later claim my brother. A few years afterward, an aunt dropped dead of a heart attack on an icy Chicago street just a few blocks from our house.

Then my beloved father died when I was thirteen, leaving me with a gaping wound of grief that did not heal for many years. Eight months later another uncle, the husband of my fathers closest sister, was shot in his bar during a holdup. And just before I graduated from high school, our neighbors were killed in a terrible collision between a train and their car. Their eldest daughter had been my best friend during most of my childhood.

Such unrelenting tragedy caused me to stumble through high school though, somehow, I managed to get good grades. As soon as I graduated, I fled to California for college with the hope of escaping the fingers of death that seemed to have such a firm hold on my life. I achieved some modicum of peace there, but only until my first husband was killed in an automobile accident, leaving me a widow at twenty-three, struggling to emerge from the stranglehold of so much loss and grief. These deaths contributed to the urgency I felt to work in my studio: this was my way of fulfilling my fathers mandate to make a difference while also satisfying my burning desire to make art.

I graduated from UCLA in 1964 a year after my husband died with a masters degree in painting and sculpture. A part-time teaching job, along with the occasional sale, allowed me to spend a minimum of sixty hours a week in my studio. During this period, I discovered with some shock that not everyone shared my parents belief in equal rights for women. As a result, I spent a considerable amount of time battling the art worlds insistence that one couldnt be a woman and an artist too.

Of course, Id had my share of problems when I was in college. Most of my art professors were male, and by the time I was in graduate school, I was on a collision course with them. They did not like my imagery because the forms reminded them of wombs and breasts, which they clearly disdained. As a result, I tried to excise any hint of womanliness from my work. Although I was able to make a place for myself in the macho 1960s Los Angeles art scene, after a decade of professional practice, I became fed up with the isolation I felt as a woman artist and decided to change course. I was determined to figure out a way to reconcile my gender and my artistic ambitions in an altogether new artmaking practice, one that would become known as feminist art.

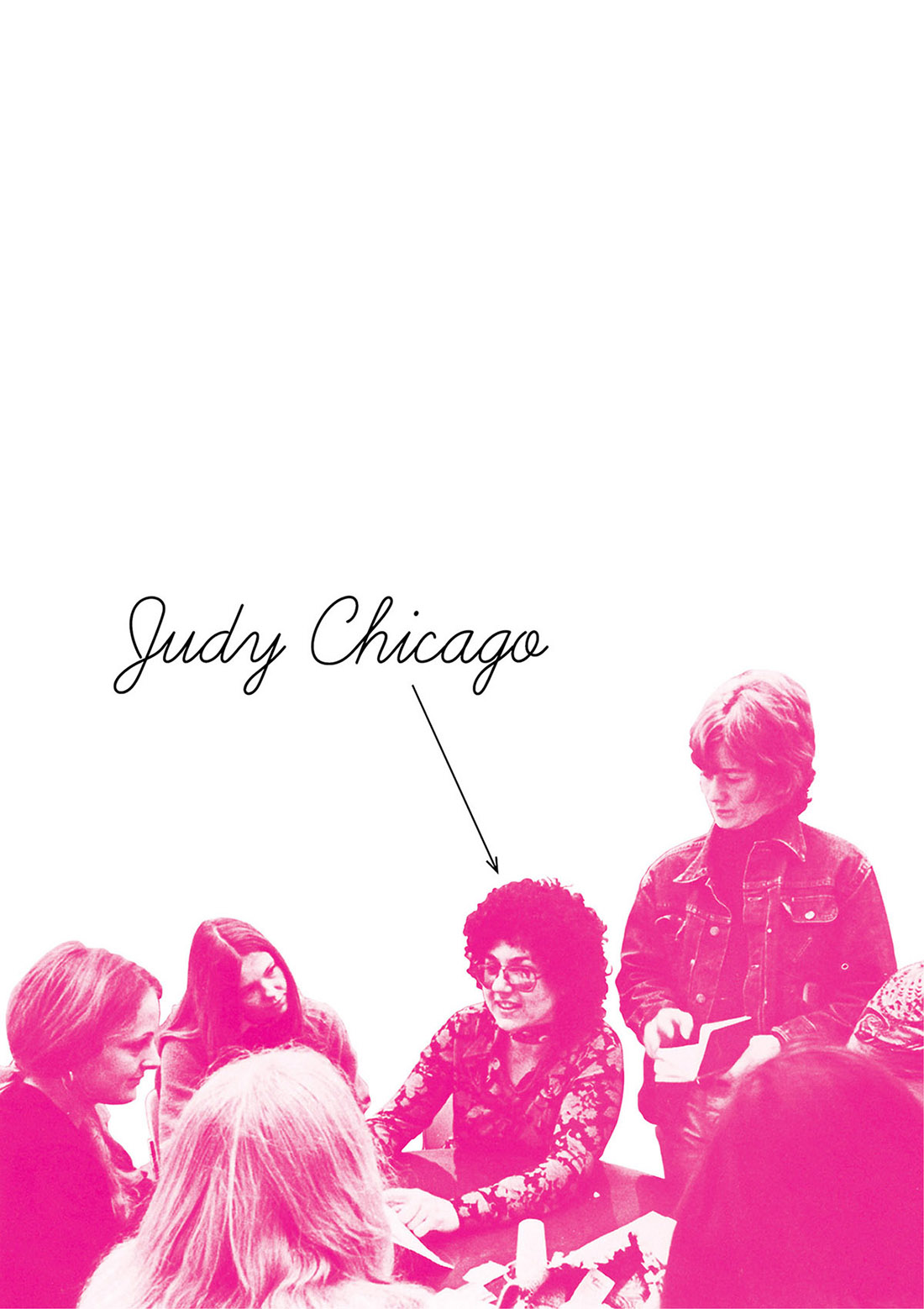

One challenge was that, in order to be taken seriously as an artist in L.A., I had severed my artmaking style from my personal impulses as a woman. As a first step towards reconnecting these, I took a full-time job at Fresno State College (later, California State UniversityFresno), where I created a studio art program for women. My hope was that by helping young female students construct an artistic identity that fuses their gender with their art, I would be able to accomplish this same goal in my own work.

In the process, I developed a radical new pedagogy, one that I came to intuitively. At that time, there was no precedent for an art course tailored to the needs of women. In order to convince the department chair to allow such a class, I argued that many female students majored in art but few emerged as practicing professionals, adding that I had witnessed this attrition myself, having gone to college with many women who no longer were working or if they were, they were not visible in the L.A. art scene. Because I had achieved some modicum of success, I believed that I might have something to offer about how to forge a viable artistic career, information that was not usually available to women.

Lastly, as soon as I started teaching, I encountered the problem that some students were not participating, which was unacceptable to me, probably because I had inherited my fathers passion for equality. During the frequent political discussions that had taken place in my childhood home, my father always made sure that everyone spoke up by employing what I would later describe as a circle methodology that involved asking each person in the room his or her opinion. By applying his example, I discovered that, in addition to encouraging a more equitable environment, this approach made everyone feel as though their views were worthwhile and also created a communal atmosphere of support and strong group bonds that seemed to accelerate the learning process. This was in sharp contrast to the competitive atmosphere in most art classes.

The Fresno course was structured so that the students were able to devote most of their class time for a year to learning how to be artists while engaging in an intensive inquiry into womens history, art, and literature. Earlier, I had begun a similar self-guided study tour, one that had changed my life by providing me with both a sense of my own history and considerable pride in womens achievements. I shared my discoveries with my students and watched them gain a comparable sense of empowerment as they made this heritage their own.