Contents

Guide

Page List

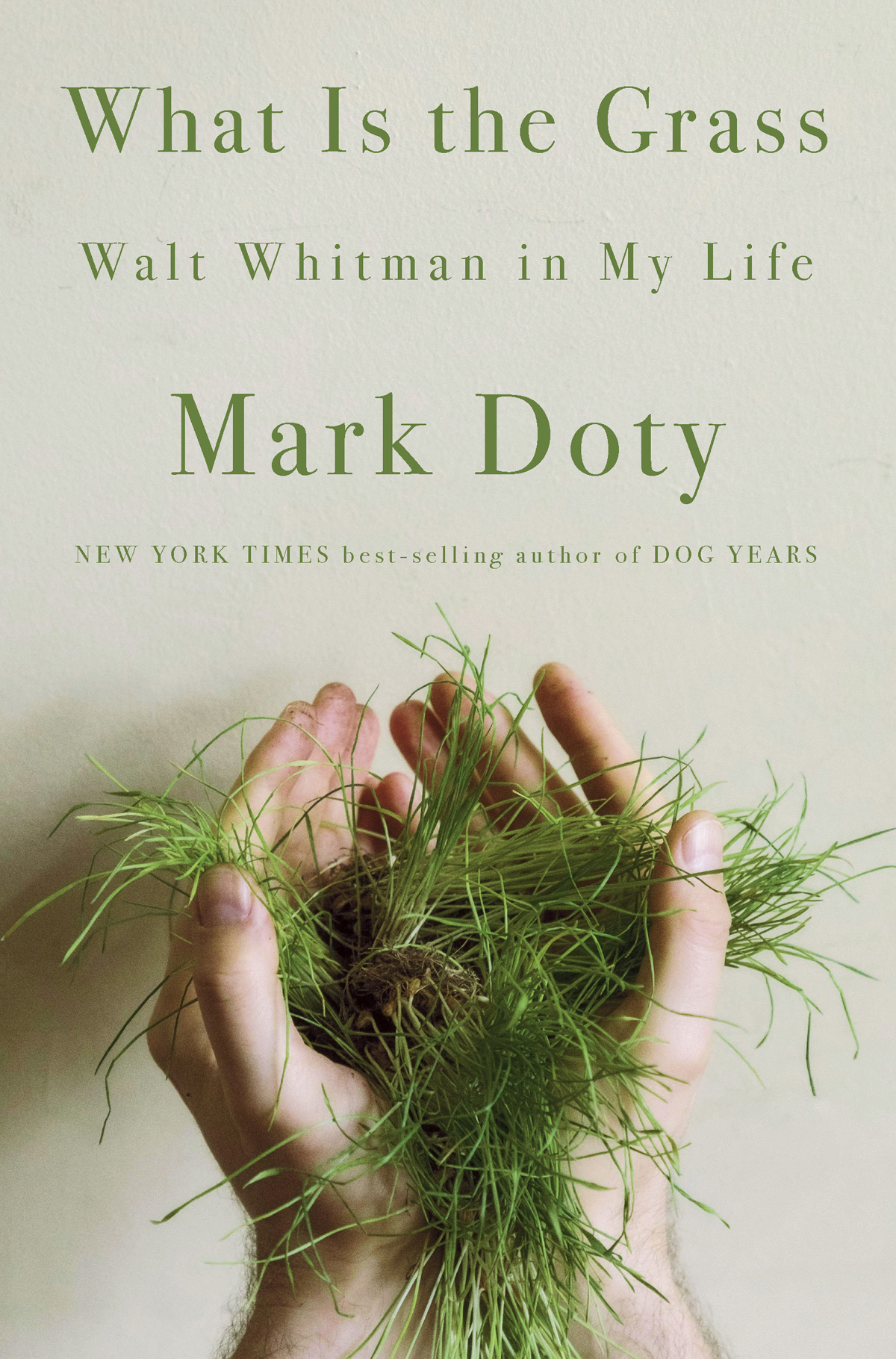

WHAT IS

THE GRASS

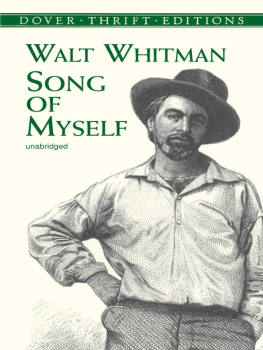

WALT WHITMAN

IN MY LIFE

Mark Doty

The best use of literature bends not toward the narrow and the absolute, but toward the extravagant and the possible.

Mary Oliver, Upstream: Selected Essays

Who knows but I am enjoying this?

Who knows but I am as good as looking at you now,

for all you cannot see me?

Walt Whitman, Crossing Brooklyn Ferry

CONTENTS

WHAT IS

THE GRASS

W alt Whitman spent his final years in a two-story, wood-frame house on Mickle Street in Camden, New Jersey, less than half a miles walk from the Delaware River, though in those days, after his debilitating stroke, hed have been pushed there in his wheelchair by an attendant. Mickle Street long ago became Mickle Boulevard, then Dr. Martin Luther King Boulevard, a wide thoroughfare that funnels drivers through an inner citys battered edge toward attractions along the river, south of the Walt Whitman Bridge: a ferry dock, a bandshell for concerts, an aquarium with jellyfish and sharks.

The street was bristling with life the year of my first visit, 1996, though the towering Camden County Correctional Facilitywindowless, anonymous brickrose just across the street from the yellow clapboards of the poets house. What message was intended, to the boys and young men diving after each other in mock battles, playing basketball on the edge of the street, hanging out on stoops or narrow porches outside the rowhouse doors? Whitmans place seemed set apart, as though it breathed the quieter air of another day, and the neighbors ignored it.

The house, now a museum operated by the state, keeps limited hours. You ring the bell and, if its an open day, are admitted by a docent, pay an admission fee, and are offered a pamphlet about the poet and his history. I hear that the place has been polished a bit in the twenty years since my visit and has more of a professional sheen. But the way it looked then is indeliblein part because when I went back, not long ago, Id forgotten to call ahead, and the place was closed. I had to content myself with looking around outside, and noticing how many of the neighboring houses were gone now, grassy lots in their place. The people were gone, too, though the jail faade had lost none of its faceless solidity.

No matter, really, that Id found the doors locked; I could remember that first time. I loved the honey-colored light filtered through the shades, and his leather backpack, wonderfully crumpled. The old mans bed upstairs, heaps of books and papers on the floor around it just as he might have left them. Not, Im a little embarrassed to report, unlike the floor of my own writing studio, where chaos can hold sway for some time before the rage to order coincides with the time to actually do something about it. The few rooms open to visitors were occupied by display cases filled with rather dutifully framed documents: letters from important persons, newspaper clippings, and invitations to banquets in the poets honor, complete with menus.

Across the river that long-ago morning, in the American Literature Collection at the Rosenbach Museum and Library in Philadelphia, a helpful librarian cheered me on, pressing into my hands Isadora Duncans copy of Leaves of Grass. The famous bohemian had danced these poems, as it were, found in them the pulse of her own freedom and nerve. She styled herself as a Barefoot Classical Dancer, emulating poses on Grecian urns and the Parthenon friezes with an unrestrained physicality, an exuberant, natural sort of movement. Though she was detained on Ellis Island with her new husband, the Russian poet Sergei Yesenin, and denounced in Washington as a Bolshevik hussy, she launched an American tour, and in 1922 danced barefoot in Cleveland in Attic costume, one breast bared. The young Hart Crane was in the audience that evening; the poet wrote to a friend that among all who attended, he was the sole spectator who had applauded.

Walt Whitman, Isadora Duncan, Hart Crane: could a list of artists be more American? Visionaries, outsiders and exiles, sexual pioneers, half-cracked, devoted wholeheartedly to unconventional notions of beauty, each longed for community and kindred spirits, and each stood mostly alone. They created the template of the American artist, who stands, as E. M. Forster wrote of the great Greek poet C. P. Cavafy, at a slight angle to the universe. Ignored, often reviled in their own times, theyve come now to embody them; their singular lights turn out to have been illuminating the way ahead all along. Add to their number Joseph Cornell, Marsden Hartley, Georgia OKeefe, Gertrude Stein, Langston Hughes, Marianne Moore, Gwendolyn Brooks (a far more experimental poet than shes generally thought to be), Jack Spicer, Eileen Myles, and trace the sturdy vine of an American tradition. What can be seen from the marginfrom Brooklyn Ferry or its inheritor the Bridge, from the unexpected vistas available from the Acropolis or Ghost Ranch, the florid modernism of a Paris salon or cheap East Village rooms in the 1970smakes its way toward the center, opening pathways for a larger culture.

But it was hard, that afternoon in the cluttered house on Mickle Boulevard, to feel any sort of vitality transmitted forward. Whitmans family had left nearly all his possessions in the house. Too many mementos of the public life, stuff that might have gone into the scrapbook or attic of an elder poet wanting to be reminded who he once was. (Before you hear too much of a snarl in that comment, be aware that I have boxes of such material myself.)

I moved from one scrap of paper to another, feeling my interest drift. I heard the raucous banging from the street, the yawps of kids, the skittering pops of firecrackers. It was high summer, after all. Why linger in the archive, pages grown yellow in the warm amber leaking through the window shades? If you want me again, the poet had written, look for me under your bootsoles. What could be the point in wandering here, among these dry bits of evidence, looking forwhat?

Then, on the topmost shelf in a glass display case, what Id never have expected: a stuffed bird, a bit dilapidated, but poised and alert as taxidermy could manage. A deep, pleasing green. A conure maybe, a lorikeet, some sort of small parrot? He looked cheerfully and expectantly out at the world forever from a wooden box sealed with a pane of glass of its own, as though he were the occupant of a construction by Joseph Cornell. His eyes were glass, the liquid originals long lost to time. Firmly dead as he was, maybe all the more so for having been made immortal, he was nonetheless the first sign of the actual life lived here.

Intimate moment, breathing air.