Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

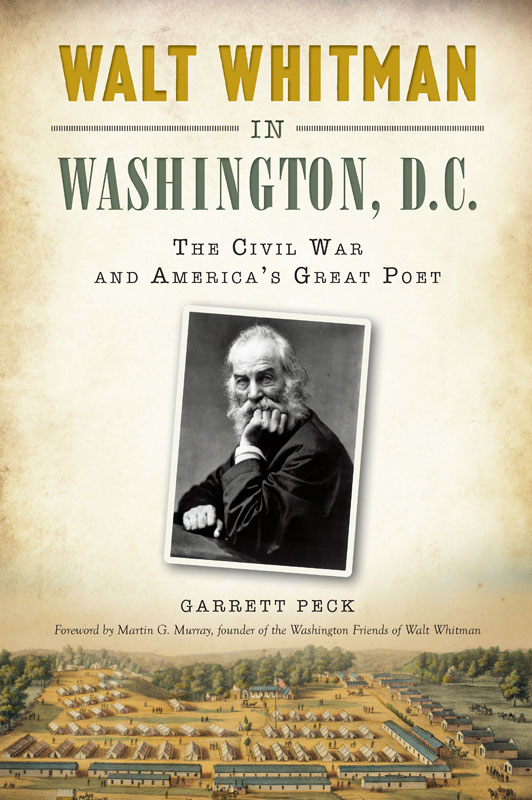

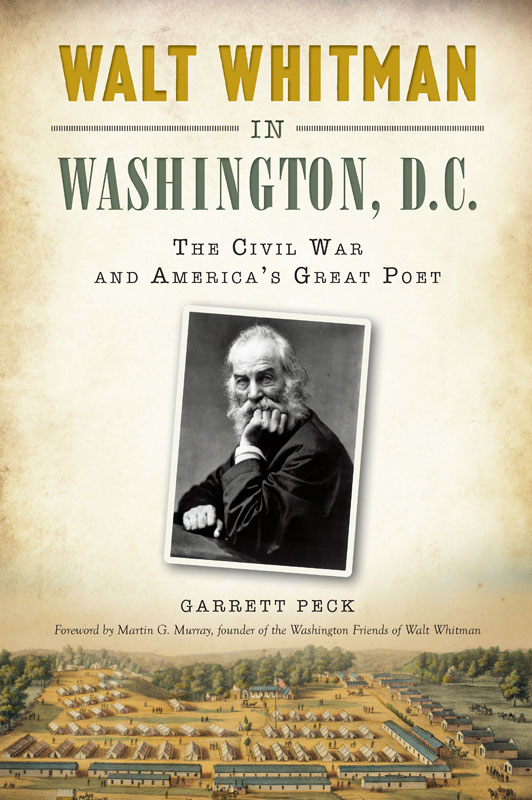

Copyright 2015 by Garrett Peck

All rights reserved

Front cover, bottom: Campbell Hospital. Courtesy of the Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.485.8

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014959296

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.973.6

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Also by Garrett Peck

The Prohibition Hangover: Alcohol in America from Demon Rum to Cult Cabernet (2009)

Prohibition in Washington, D.C.: How Dry We Werent (2011)

The Potomac River: A History and Guide (2012)

The Smithsonian Castle and the Seneca Quarry (2013)

Capital Beer: A Heady History of Brewing in Washington, D.C. (2014)

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

This is the city and I am one of the citizens, declared Walt Whitman in his signature poem, Song of Myself. Whatever interests the rest interests me. Garrett Pecks engagingly written and amply illustrated guide demonstrates how Whitman immersed himself in Washingtons urban fabric while living here from 1863 to 1873. Whitman relished his roles as hospital visitor, loving comrade, federal employee and journalist, all in support of his lifelong vocation as Americas poet.

Initially drawn to Washington to nurse his brother George, who was wounded in a Civil War battle, the forty-three-year-old Walts embrace soon encompassed an army of sick and wounded soldiers housed in Washingtons hospitals. Supporting himself by copying reports for the army paymaster, he also began to provide the local and New York presses with compelling descriptions of his hospital visits. These experiences formed the genesis of his wartime poems, a collection entitled Drum-Taps. Whitman channeled the Unions grief at President Lincolns assassination in his powerful elegies, When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomd and O Captain! My Captain! Remaining here after the war, Whitman published a major prose work, Democratic Vistas, about the evils of postwar materialism and two more editions of his poetry collection Leaves of Grass. He found emotional succor in friendships with soldier Lewis Brown, abolitionists William and Ellen OConnor, former publisher Charles Eldridge, naturalist John Burroughs, journalist Crosby Stuart Noyes, statesman James Garfield and horsecar conductor Pete Doyle, a former Confederate soldier whom biographers take to be the poets lover. Government employment was a good fit for the middle-aged poet, and he served as a clerk with the Interior Departments Office of Indian Affairs and the U.S. attorney general. Following a stroke in 1873, Whitman moved permanently to Camden, New Jersey, allowing George to play caregiver to Walt. The poet died on March 26, 1892, and is buried in Camden.

Although living in Washington for a mere decade of his seventy-two years, Whitman devoted nearly a third of his autobiography, Specimen Days, to his years in the nations capital. Pecks emphasis on the citys importance to the poet follows Whitmans lead and is a welcome addition to efforts made by other scholars and enthusiasts. The Washington Friends of Walt Whitman (WFWW), which I formed in 1985, has also attempted to do its part in promoting Walts D.C. legacy. Two recent events are emblematic. In 2005, we spearheaded DC Celebrates Whitman: 150 Years of Leaves of Grass. Chaired by the incomparable Kim Roberts and presented in partnership with local arts and culture organizations, the citywide celebration featured a wide array of readings by D.C.-based poets influenced by Whitman, tours of local sites associated with the poet and a marathon reading of Whitmans poetry. It culminated with the citys naming a segment of F Street Northwest (in front of the National Portrait Gallery where Whitman nursed wounded soldiers) Walt Whitman Way (see http://washingtonart.com/whitman/walt.html). In 2013, coinciding with the 150th anniversary of Whitmans arrival in D.C., WFWW cosponsored a conference on Whitman and Melville in DC: The Civil War Years and After with the Melville Society, George Washington University and Rutgers UniversityCamden. Conference coordinators Christopher Sten (GWU), Joe Fruscione (GWU), Tyler Hoffman (Rutgers) and I oversaw presentations by more than one hundred leading scholars from around the globe, with keynote addresses by Ed Folsom (University of Iowa), Kenneth Price (University of NebraskaLincoln), Elizabeth Renker (Ohio State University) and John Bryant (Hofstra University). The closing banquet at the Arts Club of Washington featured a musical program of Whitmans and Melvilles poetry organized by a local bass singer, David Brundage (see http://melvillesociety.org/conferences).

Garrett Pecks study adds further luster to Whitmans fame in D.C. and will surely win Whitman a new generation of admirers to gladden the old poets heart!

MARTIN G. MURRAY

Founder, Washington Friends of Walt Whitman

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As Im fond of saying, no book is written in a vacuum. I am deeply grateful for the assistance from so many people who take their inspiration from Walt Whitmans generous spirit. The poet spent ten crucial years in Washington, D.C., and this city is especially blessed with Walt Whitman admirers. Martin Murray is not only the founder of the Washington Friends of Walt Whitman but also lent his outstanding knowledge of all things Whitman, and he generously wrote the books foreword. If you visit Peter Doyles grave at Congressional Cemetery, you can admire the lilac bush that Martin planted there in 2014 in homage to Pete and Walt. Sincere thanks go as well to Sherwood Smith, another Whitman friend whose kindness rivals Walts.

Archivists and librarians are stewards of our history who open the vaults to researchers like myself. Many of Whitmans records are entrusted to the Library of Congress. Walt would be very proud of our federal clerks, as am Iespecially Dr. Alice Birney, Dr. Barbara Bair and Chris Copetas, who helped guide my research and answered my many questions. Jeff Bridgers in the Prints & Photographs Division has assisted me with many images over the years in numerous books.

Librarians are modern-day superheroes. Jerry McCoy of MLK Librarys Washingtoniana room somehow makes his way into most of my books thanks to his inquisitive mind and incredible insight into all things Washington. John Muller piqued my curiosity of the friendship between William Swinton and Mark Twain. Laura Barry at the Historical Society of Washington, D.C., is one of the most adept research assistants Ive had the privilege of working with. And the staff at Arlington Central Library patiently dealt with my endless interlibrary loan requests.

Washington is fortunate to have museums that preserve our legacies for future generations. Melissa Kroning and Eleanor Harvey have the privilege of working for the Smithsonian in the old Patent Office, where both Clara Barton and Walt Whitman worked, and both pointed out crucial Civil War material. Susan Rosenvold, the first director of the Clara Bartons Missing Soldiers Office, showed me the museum long before it opened, and Sara Florini provided a personal tour of the space afterward. Terry Reimer of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine shared her extensive knowledge of Civil Warera hospitals. Steve Livengood of the U.S. Capitol Historical Society first raised the question of whether Clara and Walt ever metand answered it with a painting.

Next page