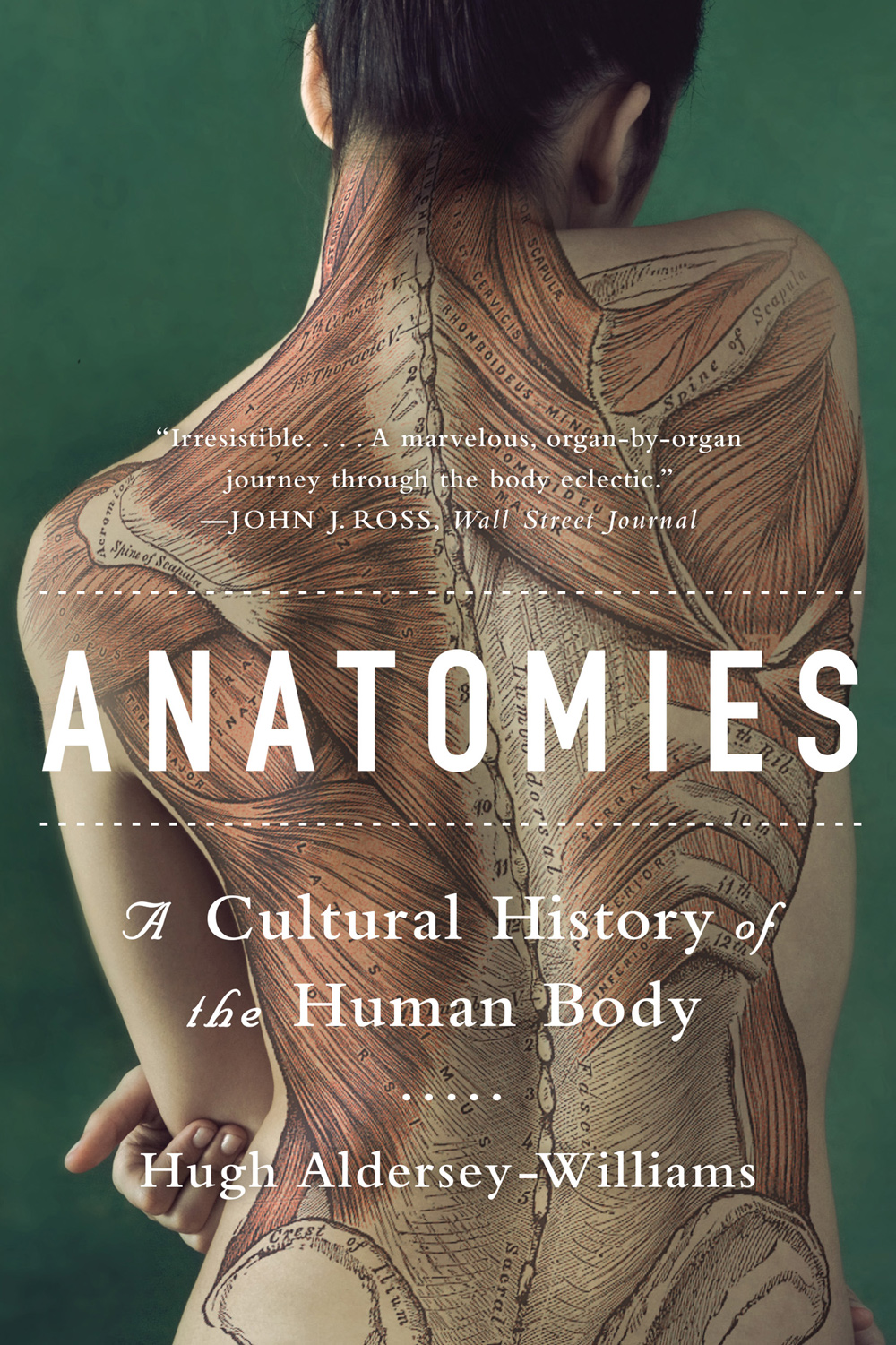

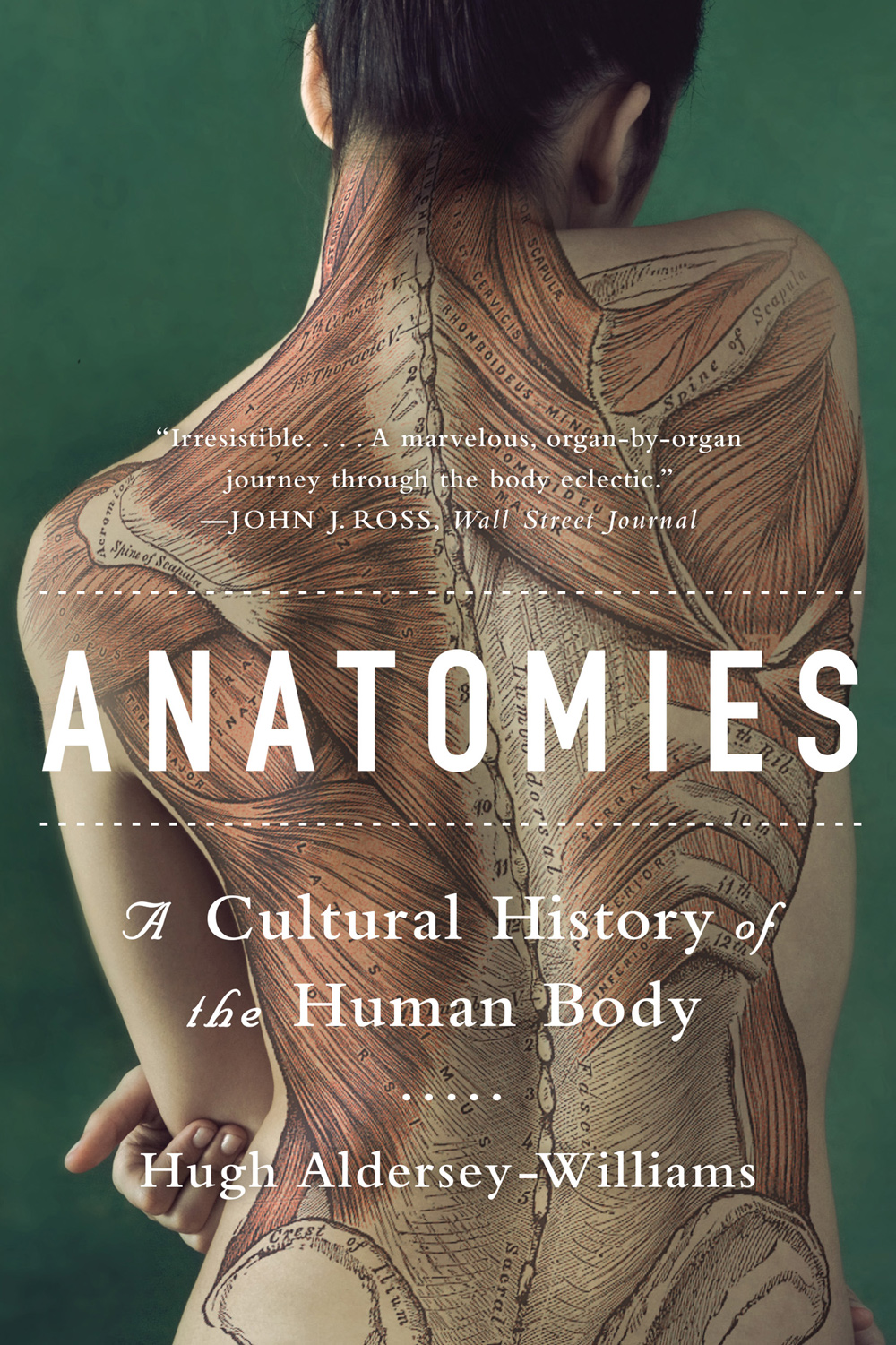

Anatomies

A Cultural History of the Human Body

HUGH ALDERSEY-WILLIAMS

To Moira

These little Limbs,

These Eyes and Hands which here I find,

These rosy Cheeks wherewith my Life begins;

Where have ye been? Behind

What curtain were ye from me hid so long?

Where was, in what Abyss, my new-made tongue?

From The Salutation, Thomas Traherne, 163774

Contents

There comes a moment in your life when you realize that you are probably not, after all, going to be the first person to live for ever.

This realization is normal, or at least I assume so, but it is quite contrary to your rightful expectation. It is a shock.

Lets be clear. Your mind has no problem with the idea of living for ever. Whats wrong with just carrying on as it is doing now? It can see no reason not to. No. Your bodys the problem. It begins to work less well. And it starts going on about itself, sending you ever more frequent messages, nagging, needy messages: What about me? Is nobody listening to me? Stop that, it hurts. Or: I need to go to the loo. What, now? your mind sleepily responds. Its three in the morning. Yes, now.

At school, I was obliged to give up biology at the age of thirteen, even though I was beginning to veer towards the sciences. One lesson a fortnight became no lesson at all. It now seems to me astonishing that this should be allowed to happen, not only because it was by then already clear that biology was the scientific speciality which offered the greatest scope for discovery, but also because we are each the owner-operator of our own human body, and this surely would have been the time to learn something about it. Instead, I was left in charge of a complex biological organism about which I knew next to nothing and yet, if I was lucky, I would be instructing and inhabiting for another seventy years or so.

One consequence of this educational omission and my own intellectual laziness is that I have no answer to the bathroom-at-three-in-the-morning problem. I have no idea how my bladder works, or why it seems to work differently now from the way it worked when I was younger. And the chances are that you havent either.

I have only a vague picture of some sort of watertight balloon that fills and empties itself, located somewhere in my abdomen. For more precise information, I find I must consult an undergraduate textbook. The book is like a paving slab, and its full of colourful but artless drawings. I look up bladder in the index. It is not there. I see Im going to be forced to translate my simple enquiry into an alien jargon. I consider the matter briefly, and then turn to the Us to find an entry for urinary system.

The bladder, I learn, is an elasticated bag made of thin layers of muscle. It is lined internally with mucus to make it watertight. When full, it distends to the size and shape of a large avocado and contains about a pint of urine (or a litre, according to another textbook, nearly twice as much). An accompanying X-ray image, referred to as if Im meant to know the meaning of the word as a pyelogram, shows the arrangement of the urinary system within the body, highlighted by a contrast agent that has been injected into the human subject. I see a bulbous reservoir cradled by the pelvic bones at the base of the spine. Running out of it are the two thin lines of the ureters, which hug the spine on their way up to the kidneys, where each branches into two, and then five, and then many more thinner tubes that terminate in the depths of each kidney, somewhere about level with the bottom rib of the rib cage. The image is rather beautiful, like two long-stemmed irises in a bulb vase.

The ureters are muscular tubes that squeeze the urine produced by the kidneys down into the bladder. As the bladder reaches capacity, stretch receptors in the muscle wall are stimulated, sending signals to your brain that you construe to mean that you should get up and relieve yourself.

Well, not exactly. In fact, the system is smarter than that. The bladder sends out its first signals simply to test your readiness. On this occasion, your brain responds to the news by sending a message back to the bladder that causes its muscles to contract a little, increasing the pressure of fluid within. The purpose of this is to gauge whether another set of muscles, the ones that allow the bladder to drain when they are relaxed, will hold for a bit longer. The brain is stalling, asking the bladder in effect: Do you really mean it? When the bladder sends back signals admitting that it was just a bluff, your brain responds with an instruction to the muscles of the bladder wall to relax again and allow more urine to accumulate. All this happens in your sleep, and saves your being awoken until you really need to be. Its like the snooze button on an alarm clock.

The textbooks gloss over the deterioration of this admirable system in middle age. I try to reason it out. Maybe your bladder contracts, meaning that it must be emptied more often. Or maybe it expands, triggering the stretch receptors sooner. Maybe the stretch receptors themselves become more twitchy. Maybe the neural telegraph between your brain and your bladder goes a bit haywire and starts sending the wrong messages. Maybe your ageing brain just panics and thinks better safe than sorry. There are so many possibilities. I run my theories by a friend who is a hospital consultant. Ive been trying to look it up myself, he tells me after a while, but the process has left him as baffled as I am. Finally, he passes my questions to a colleague who is a urologist. In fact, Im told, you simply produce more urine in your sleep as you get older. Its an inconvenient truth to say the least.

It seems absurd that finding an explanation of this most banal of bodily functions has required so much expert consultation. But I have more awkward questions, too. Is the bladder just a bag or is it something more? Is it an organ? What qualifies as an organ? Where do organs stop and start? Student doctors often buy themselves a plastic skeleton and a plastic model of the body in which brightly painted organs hook neatly into place alongside one another. Is this really what the body is like? Or are the organs perhaps cultural inventions, better regarded as repositories for various ideas that we have formed about life than as discrete entities in biological reality? Does it even make sense to talk about the body in parts? For whom does this make sense? And if so, is the human body merely the sum of those parts, or is it something more? For Aristotle was indeed thinking about the human body when he coined this now overworked phrase more than the sum of its parts in his Metaphysics . And if the human body is more than the sum of its parts, then what is this more?

Anatomies is my attempt to make amends for my missing education in human biology and to find answers to these questions. Like most of us, I know shamefully little about how my body actually works and occasionally doesnt. Those who do know our doctors seem keen to keep the knowledge to themselves, guarding their professional status with their long words, their simplified attempts at explanation, and those famously illegible prescriptions.

It is obvious that the human body is a difficult subject. Perhaps we are too close to it. The human body is routinely described as a marvel of nature, but it is surely the marvel of nature we least stop to observe. When all is well, we simply ignore it. I suppose this is as it should be no other animal spends time pondering its wellbeing, after all. But for us, ignorance is not bliss. We are frequently ashamed of our bodies and embarrassed by them.

Next page