H UGH A LDERSEY -W ILLIAMS

DUTCH LIGHT

Christiaan Huygens and the Making of Science in Europe

Contents

To Sam

List of illustrations

M ONO P LATES

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

C OLOUR P LATES

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

Authors note

My principal primary source has been Christiaan Huygenss Oeuvres Compltes, which contain the letters of Huygens and his correspondents in French, Latin, Dutch and other languages, as well as the texts of his major treatises in their original languages. They also include the editors summaries of Huygenss scientific achievements and a concise biography in French. I have made my own translations when quoting from this source or from manuscript originals held in the library of the University of Leiden. Many of the secondary sources I consulted are in Dutch (or occasionally another language), and in these cases, too, I have made my own translations, including excerpts of verse, except when a preferable translated text has been available, in which case it is cited in the Notes.

Dates are New Style except where indicated.

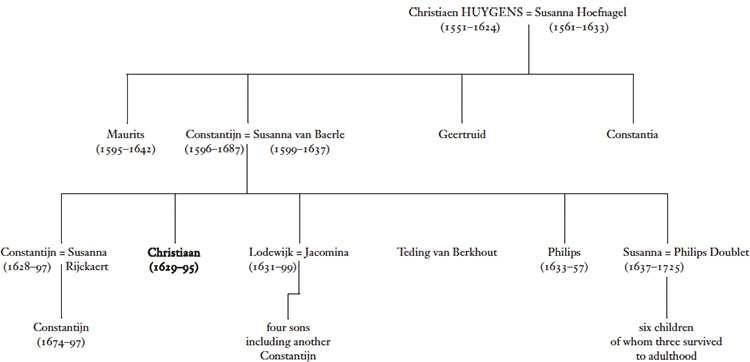

T HE H UYGENS F AMILY ( PARTIAL )

I NTRODUCTION

Light lances through the leaded panes and strikes the polished black-and-white tiled floor of the room, imposing one grid at an angle upon another. It crooks as it meets the window surface and crooks again after it has passed through to resume its original direction. It dances and twists, dodges and swerves round imperfections in the old glass. Here and there, tiny blemishes improvise lenses and prisms, which produce magnified and distorted flecks and gobbets of light on the floor, and sometimes a tiny rainbow. The brightest pattern of light is the one cut by the sharp shadows of the lead in the window. This falls off to one side because of the suns position in the sky. But there is another pool of light, too. Directly below the window, a hazy bluish gleam rises from the tiles, which is the reflection of the light of the sky.

The room is large and bright and was originally used for dinners and musical entertainments. It has windows on three sides, but is even brighter than youd expect for that. It is almost like being outdoors, which seems odd at first because overhead is not air but a heavy beamed ceiling. Then you realize that this ceiling is almost glowing with light itself, light from yet another source, coming from below the horizon and projected upward through the same window by the water in the moat that surrounds the Huygens house, known as Hofwijck.

This estate three miles south-east of The Hague is where Christiaan Huygens lived after the death of his father, the poet and diplomat Constantijn Huygens, until his own death just eight years later, in 1695. When Constantijn built Hofwijck some fifty years earlier, he wrote that he wanted it to appear as if by night , / It grew, like a mushroom revealed in the light. And so, amid its calm, reflecting waters and with the elevated motorway now roaring too close by, it does, even today. Here, Christiaan finalized treatises on the nature of light and gravity that summed up his prodigious contribution to physics. Here, he set up his telescopes in the spacious grounds and began to speculate about life on other planets.

Christiaan Huygens was Europes greatest scientist during the latter half of the seventeenth century, until the rise of Isaac Newton, by whom he has been largely eclipsed, especially in English-speaking parts of the world.more accurate clocks, realizing the vision of Galileo before him. His innovations in optical instrumentation and timekeeping are still in use today.

Huygens also had range: he was a fine draughtsman, a skill of use not only in designing mechanical and optical devices but also in representing to the world the planetary phenomena he observed through his telescopes, although he was not above making sketch portraits to flatter girlfriends, or little landscapes of the countryside in which he found himself. He was a proficient musician, joining in with performances wherever he went. Occasionally, a few notes of a melody or a lyric for a song are to be found in the margins of his scientific notes. But he also wanted to bring his mathematical science to bear in music, proposing a division of the octave into thirty-one notes, foreshadowing musical innovations of the twentieth century.

More lasting in significance were his efforts to elevate science itself in Europe, both in the Dutch Republic and, more especially and surprisingly, in France, where he was instrumental in the establishment of the French Academy of Sciences. He was also an early fellow of the Royal Society of London, becoming a personification of the potential for science to transcend national borders.

This was not always how he chose to appear to the world, however. When Huygens returned from Paris to The Hague in 1671, he sat for his portrait to be painted by Caspar Netscher, who had already painted several other family members. Netschers small oil painting demonstrates the artists mastery in representing fine fabrics. Huygens looks out with wide eyes from amid an ocean of silk and lace. He is at the height of his powers, and yet there is still something about him of the pretty child he once was. If we are in search of a display of learning perhaps a table nearby with scientific instruments and papers of calculations lying casually on top then we will have to look elsewhere. This is above all a man of fashion and extravagant taste.

But he was, too, the prototype of a modern scientist. Although he explored many topics, and shuttled between them opportunistically, rather than pursuing what would today be called a programme of research, he conducted his investigations with diligence and rigour, even if, like many others at the time, he did not always rush to publish his findings. His employment of mathematics as well as his awareness of the importance of criteria of reproducibility, verifiability and falsifiability the understanding that experiments should be repeatable in order to demonstrate their truth, and that experimental results that fail to support a hypothesis must lead to rejection of the hypothesis reveal the essential seriousness of his project. His topics were well chosen as ones where a breakthrough might realistically be achieved. He did not wander off the track into the realms of superstition, which is more than can be said for some of his contemporaries. So dedicated to learning was he that, on his first visit to London in 1661, he turned down the chance to attend the coronation of King Charles II in order to observe the more interesting transit of Mercury.

This all-round proficiency Huygens undoubtedly perfected with the help of Constantijn, the father who first doted on him and then stood in awe of his sons talents, introducing him as my Archimedes to Descartes and other illustrious visitors to his household. The long-lived Constantijn was a strong moral and intellectual influence for almost the whole of Christiaans life so much so that when he eventually died at the age of ninety, Christiaan, by then fifty-eight years old, morosely had himself painted in the garb of an orphan.