Foreword copyright 2020 by Fred D. Gray

All rights reserved

Published by Lawrence Hill Books

an imprint of Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

FOREWORD

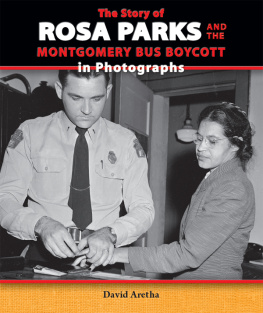

A LOT HAS BEEN WRITTEN about the Montgomery bus boycott, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Rosa Parks, including what I wrote in my own book, Bus Ride to Justice, recounting my involvement as the boycott attorney. So when Karen came to me to let me know she was working on a manuscript about that pivotal moment in our nations history, I was curious about the approach she would take, though confident it would be interesting, engaging, and informative.

As her uncle, I admit to being somewhat biased. Karen is the daughter of one of my older brothers, the late Judge Thomas W. Gray Sr., and his wife, Juanita. The two of them didnt live to see this book published, but you will meet them on the pages of Daughter of the Boycott, and you will understand how they produced an offspring who appreciates how they lived their lives, becoming displaced refugees as they fought back against a segregated system that tried to hold them down.

Our entire family was touched in some way by that historic boycott. Karen was only four years old in 1955, when Montgomerys African American citizens stopped riding city buses for 382 days to protest the way we were treated, seeking an end to racial discrimination. Her father was one of the original members of the board of the Montgomery Improvement Association, which coordinated the boycott. Tom also drove his car to pick up African American passengers and was later arrested along with eighty-eight other activists, including myself. They were charged with violating the states anti-boycott laws. I was accused of representing one of the plaintiffs without her consent in the federal case that desegregated busing, Browder v. Gayle. That indictment was dismissed.

Toms daughter and two sons were probably too young to understand the magnitude of what was happening, but they were old enough to feel the slights of being told to drink from colored water fountains, to know they wouldnt be served inside some stores and restaurants, to be called the n-word by strangers.

Im certain many of Karens friends and former work colleagues will be surprised to learn that her family didnt just move to Cleveland as part of the Great Migration, when African Americans sought a better life up north. The reason comes alive in the book, along with many other stories Karen came across as she went digging for tales she never knew about the boycott. At the outset, I spent many hours talking to her about what I knew and my experiences. She tagged along with me on many of my speaking engagements around the country as she formed an opinion about the boycott legacy.

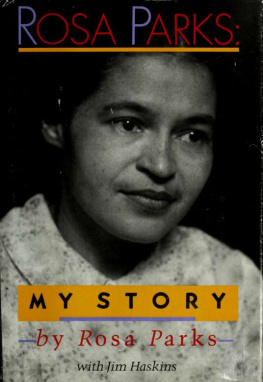

Inquisitive, intrepid reporter that she is, during her research Karen discovered information that had been locked away for years in a closetangry, hateful letters written to white city officials and the bus company being boycotted, now being kept in the Alabama Department of the Archives and History. She combed Rosa Parkss personal papers, now housed at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, for new insight. A white woman introduced her to the maid she employed during the boycott. Struggling to understand what the yearlong protest meant to her, my niece talked to the daughter of Montgomerys police commissioner, known for his rabid efforts to keep segregation in place. She traveled to New York City to an auction of boycott financial papers, long hidden from view.

Karen is a great storyteller. The tone of Daughter of the Boycott is comfortable and conversational. It goes behind the scenes to look at whites who fought along with us, and at white enemies who used bombs, rhetoric, and other tactics against us. She also spoke to one boycott insider, once labeled a traitor by the movement. I found the book to be enlightening and educational with a view of the boycott you havent seen before and will not see hereafter.

As a civil rights attorney whose career has spanned sixty-four years, I am often asked about the progress African Americans have made. People want to know if the civil rights movement was a success. How far have we come and how far do we have to go?

My activities in connection with the Montgomery bus boycott were just the beginning of my career in the legal profession, which included cases that eliminated racial discrimination in almost every aspect of American life, including the right to public transportation, to vote, to protect the membership of organizations, and to public education without discrimination, as well as equal access to farm subsidies, health care, and the right to serve on civil juries.

Yes, we have made substantial progress. Yet, as Daughter of the Boycott points out, desegregated schools are, years after the battle, largely resegregated. Racial profiling and police brutality remain as challenges. In addition, the National Urban Leagues 2018 State of Black America report states that the equality index can be interpreted as the relative status of blacks and whites in American society measured according to five areas: economics, health, education, social justice, and civic engagement. In each there is substantial disparity having a negative effect on African Americans as compared to white Americans. The report also states that African Americans are twice as likely as whites to be unemployed, three times more likely than whites to live in poverty, and more than sixteen times as likely to be incarcerated.

I agree with this report. It demonstrates as well as Daughter of the Boycott the fact that the struggle for equal justice continues.

FRED D. GRAY, ATTORNEY AT LAW

GRAY, LANGFORD, SAPP, MCGOWAN,

GRAY, GRAY & NATHANSON

AUTHOR, BUS RIDE TO JUSTICE AND

THE TUSKEGEE SYPHILIS STUDY

PREFACE

THE 1955 MONTGOMERY BUS BOYCOTT was a powerful example of how extraordinary results can spring from the efforts of ordinary people. For 382 days, forty-two thousand African American citizens stood up to the ruling white majority and white supremacists in Alabamas capital city to demand the simple right to sit where they wanted to, instead of having to endure the daily humiliation of being segregated in the back of city buses. Two of the leaders of that boycott were my father and my uncle.