TO CORETTA

my beloved wife and co-worker

CONTENTS

I

Return to the South

II

Montgomery Before the Protest

III

The Decisive Arrest

IV

The Day of Days, December 5

V

The Movement Gathers Momentum

VI

Pilgrimage to Nonviolence

VII

Methods of the Opposition

VIII

The Violence of Desperate Men

IX

Desegregation at Last

X

Montgomery Today

XI

Where Do We Go from Here?

INTRODUCTION

When the history books are written in the future, somebody will have to say, There lived a race of people, a black people a people who had the moral courage to stand up for their rights. And thereby they injected a new meaning into the veins of history and of civilization.

Delivered at Montgomerys Holt Street Baptist Church on December 5, 1955

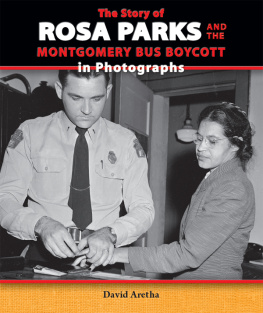

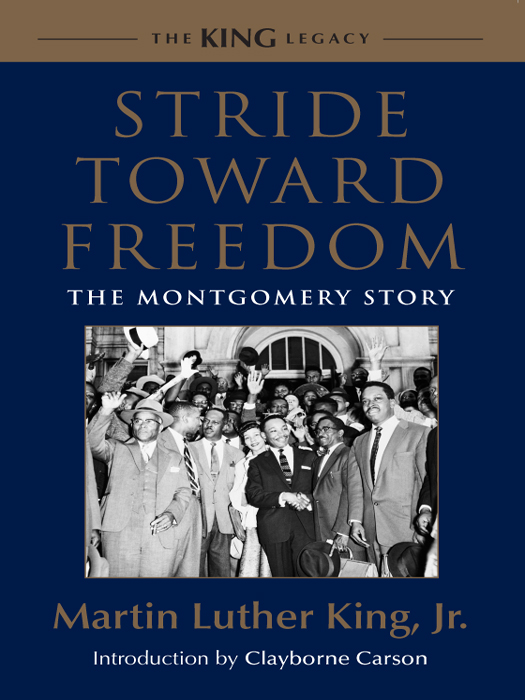

With no certainty that the one-day bus boycott on December 5 could be sustained long enough to succeed, twenty-six-year-old Martin Luther King, Jr., predicted that the protest sparked by Rosa Parkss arrest would have lasting historical significance. The boycotts initial goals were modestcourteous treatment by bus drivers and first-come, first-serve seating, with black riders taking seats from the rear to the front of the bus. Nonetheless, King sensed that Montgomerys black residents had joined a momentous national and even international movement seeking goals beyond fair treatment on buses. In the aftermath of World War II, long-established systems of racial domination were being challenged throughout the world. In 1945 the newly formed United Nations had refused to take a firm stand against colonialism but three years later approved the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, giving moral support to struggles against colonialism and all forms of racial discrimination. By then, the decades-long protest campaign in India inspired by Mahatma Gandhi had achieved independence from British control. Pakistan, Burma (now Myanmar), and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) also became independent nations. Elsewhere in Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean, anticolonial movements gained strength, as more than four dozen nations declared their independence during the next two decades. In the United States, African Americans intensified their long struggle against racial barriers, insisting that the nation live up to the democratic ideals it affirmed in the war against fascism and Nazism as well as the subsequent Cold War against communism. The NAACPs Legal Defense Fund, led by Thurgood Marshall, won major legal victories that weakened the prevailing separate but equal doctrine established by the Supreme Courts Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896. The Supreme Court overturned this doctrine when it unanimously declared public school segregation unconstitutional in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision of May 1954.

Although Brown had little immediate impact on school segregation, it encouraged African Americans to believe that the entire southern Jim Crow system of enforced racial segregation and discrimination could be overcome. Before the decision was announced, King and his wife Coretta had decided to return from their studies in Boston to their native South after concluding that something remarkable was unfolding in the South, and we wanted to be on hand to witness it. The son and grandson of Baptist preachers who had also been Atlanta civil rights leaders, King had been an ordained minister since 1948. He attended Morehouse College, where he became inspired by the service ethic of President Benjamin E. Maysone of the great influences of my life, King enthused in Stride. King then prepared for the ministry by continuing his studies at Pennsylvanias Crozer Theological Seminary and at Boston Universitys School of Theology, where he received his doctoral degree in June 1955. Kings Crozer application explained that an inescapable urge to serve society had spurred his call to the ministry, and his seminary and graduate studies deepened his understanding of the peace and justice message of Christianity. In his sermon accepting the offer to become pastor of Montgomerys Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, King informed his congregation that he was committed to a social gospel ministry: I have felt with Jesus that the spirit of [the] Lord is upon me, because he hath anointed me to preach the gospel to the poor, to heal the brokenhearted, to preach deliverance to the captives, and to set at liberty them that are bruised. Even before the Kings settled in Montgomery during the fall of 1954, local civil rights activists were mobilizing their own campaign against the southern Jim Crow system. Just days after learning about the Brown decision, Jo Ann Robinson, head of Montgomerys Womens Political Council, wrote to the citys mayor criticizing mistreatment of black bus riders. When King was formally installed as Dexters pastor, he named Robinson as cochair of the churchs Social and Political Action Committee, with a mandate to encourage voter registration by members and to keep the congregation intelligently informed concerning the social, political and economic situation. King soon became involved in civil rights activities, speaking at meetings of NAACP branches in Birmingham and Montgomery. When fifteen-year-old high school student Claudette Colvin was arrested in March 1955 for violating Montgomerys bus segregation ordinance, King joined Robinson, Parks, and other black residents to meet with city and bus company officials. By the time of Parkss arrest on December 1, black residents were prepared to resist degrading treatment. Even though other local leaders were more responsible for organizing the initial boycott, King enthusiastically assisted the effort and quickly gained the respect of Robinson and NAACP stalwarts such as Parks and Pullman car porter and labor activist E. D. Nixon. Thus, it was not entirely surprising that local leaders turned to the youthful newcomer to the city to head the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) that they had formed to carry on the boycott.

Although he did not expect to become head of the MIA, King understood the boycotts broader implications. His hastily prepared speech that evening audaciously linked the MIAs modest initial objectives to American political principlesIf we are wrong, the Supreme Court of this nation is wrongand Christian idealsIf we are wrong, Jesus of Nazareth was merely a utopian dreamer that never came to earth. If we are wrong, justice is a lie. The boycotts goal soon became the desegregation of the citys buses, and the 381-day campaign in Montgomery spurred a sustained mass movement to overcome the entire southern system of legalized segregation and racial discrimination. Kings subsequent speeches, public statements, and published writings would transform the Montgomery movement into a milestone of the African American freedom struggle and confirm his prediction of its place in history.

Written less than two years after the successful completion of the boycott, Stride is both the first book-length history of the Montgomery movement and the first of Kings trilogy of political autobiographiesit would be followed by Why We Cant Wait (1964) and Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (1967). Soon after the successful completion of the boycott, William Robert Miller, assistant editor of Fellowship, the pacifist journal published by the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), encouraged King to write his account of the boycottYou have a vital message for this country and the world. In addition to his academic writings, King had published a number of articles since calling for equal rights in a letter to the editor of the