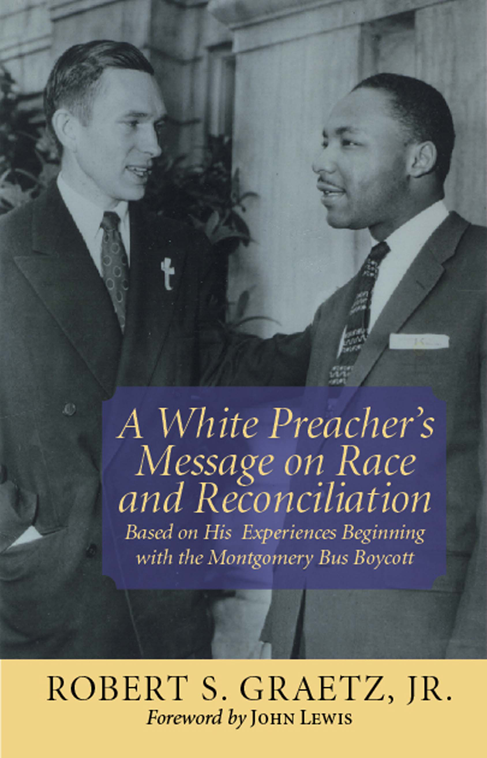

Robert S. Graetz

P.O. Box 1588

Copyright 2006 by Robert S. Graetz. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by NewSouth Books, a division of NewSouth, Inc., Montgomery, Alabama.

Foreword

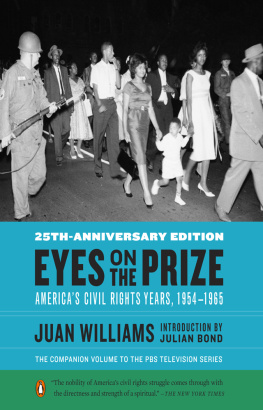

By John Lewis

With all that I have experienced in the past half century, I can still say without question that the Montgomery bus boycott changed my life more than any other event before or since. I have been reminded of this all through this excellent memoir by the Reverend Robert Graetz, who with his wife, Jeannie, was in the forefront of the boycott.

Montgomery was just fifty miles away from where I grew up in rural Alabama. Id been there only once myself, on a day trip I took by train in my seventh-grade year. But my parents and my neighbors knew Montgomery. Our minister lived there. Most of my teachers were from there. Even though we lived far out in the Alabama woods, we were connected to Montgomery in many ways. We were part of the place. And when that young minister, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in his role as the president of a group called the Montgomery Improvement Association, launched a black boycott of the buses after the arrest of Rosa Parks, we felt we were a part of that as well.

Robert Graetz was an active member of the board of directors of the Montgomery Improvement Association and he was the minister of a Montgomery African American church during the boycott. Even his home was bombedtwice.

You can appreciate that I was more than a little surprised to learn all this about Reverend Graetz when I met him in later years and saw that he was a white man. What an amazing thing it was that a white man would be the pastor of a black congregation in Alabama in 1955 and that he and his family would live in a black neighborhood and they would all be completely committed to the goals and principles of the bus boycott and the larger civil rights movement. The book you are now reading explains where this commitment came from, and shows how Bob and Jeannie Graetz have lived lives dedicated to bringing about what Dr. King called the beloved community.

The Montgomery boycott went on for more than a year, and I followed it almost every day, either in the newspapers or on radio. This was riveting. It was real. This wasnt just talk. This was action. And it was a different kind of action from anything Id heard of before. This was a fight, but it was a different way of fighting. It wasnt about confrontation or violence. Those fifty thousand black men and women in Montgomery were using their will and their dignity to take a stand, to resist. They werent responding with their fists; they were speaking with their feet.

There was something about that kind of protest that appealed to me, that felt very, very right. I can see in Reverend Graetzs account of his life that he felt the same way. We may not have started out as practitioners of nonviolence or passive resistance, but when shown the way by the eloquent example of Dr. King, we knew instinctively that nonviolence was not only the right strategy but also the right way to live.

Over the years that followed, I left rural Alabama and went off to school and then I got totally involved in the civil rights movement, from the sit-ins to the freedom rides to the voter registration campaigns. My journey, which I tell about in my own memoir, Walking with the Wind , eventually took me to the U.S. Congress, where I am proud to serve today. But over the years I have stayed involved with many of the people who worked with me in various phases of the movement. And I have stayed committed to the principles which were put into motion back in Montgomery and that influenced me so much when I was a young boy.

In the pages of Reverend Graetzs memoir, you see where his journey took him and his life partner, Jeannie Graetz. You see that the journey of a black youngster from the woods of Alabama to the U.S. Congress is not all that different from the journey of a white youngster from West Virginia who grew up to become a minister committed to the same principles of equal justice and civil rights.

I believe in my heart that we need to read and understand stories like those told in this book. We need to understand that people of courage, conscience, and commitment are still willing to spend their lives dedicated to the brotherhood of mankind. As I learned in my work, and as Bob Graetz clearly learned in his, the Beloved Community is nothing less than the Christian concept of God on earth.

Believers in the Beloved Community insist that it is the moral responsibility of men and women with soul force, people of goodwill, to respond and to struggle nonviolently against the forces that stand between a society and the harmony it naturally seeks.

This book shows that the Reverend Robert Graetz has done that with his life. In fact, he is still doing it.

John Lewis is a member of the U.S. Congress from the Fifth District of Georgia. The former chairman of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, he is internationally known for his courage during the civil rights movement.

Preface

In the Torah (the first portion of the Hebrew scriptures) God commanded his people to set aside every fiftieth year as a Year of Jubilee. It was to be a time of restoration. Any land that had been bought was to be returned to its previous owners. The purchasers had merely paid for the use of the land for a given period of time until the next Jubilee Year. Those who had been sold into bonded servitude were to be freed. It was Gods desire that no Hebrews be allowed to remain in permanent servitude. You shall proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants (Leviticus 25:10). God seemed to be saying, No matter how much things have gotten out of kilter, lets put them all back into their proper order.

Whether the ancient Hebrews ever observed the Year of Jubilee as instructed in Leviticus is a matter for discussion among theologians, but the God-given concept is still fitting for us today. Fifty years is long enough. If you took something that wasnt yours, even if it was fifty years ago, its time to give it back.

We are presently in the midst of a series of fifty-year celebrations of events of the twentieth century Civil Rights Movement: The 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education, and its follow-up decision in 1955, which ruled segregation in the public schools to be unconstitutional. The murder of Emmett Till in Money, Mississippi, in 1955, for whistling at a white woman. The Montgomery Bus Boycott of 195556, which led to the desegregation of municipal transportation. The Birmingham Campaign to break down racial barriers in public accommodations and jobs in the early 1960s, including the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. The Selma Voting Rights Campaign marked by the Bloody Sunday march on March 7, 1965. And others. For the next decade and more well be celebrating jubilees of the triumphs and tragedies of the modern Civil Rights Movement.