Introduction

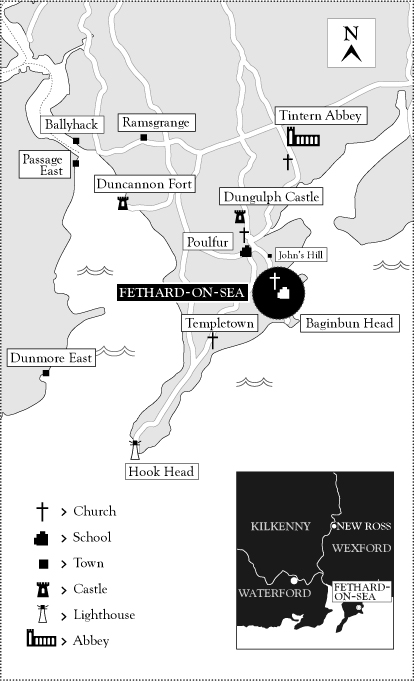

T he Hook Peninsula in County Wexford is one of the most attractive, if less well-known, parts of the country. It is not a rugged beauty like that of Connemara or Donegal. Nor is it that spectacular beauty to be found in Kerry or Clare. Instead, it has a remote, otherworldly mystery all of its own. There are few places where the past seems to hang so heavily in the air, from the haunted Victorian grandeur of Loftus Hall to the Cistercian splendour of Tintern Abbey. Fethard-on-Sea lies on the eastern side of the Hook at the entrance to Bannow Bay. Its quaint appendix, redolent of the somnolent English seaside, distinguishes the Wexford village from the landlocked town of Fethard in County Tipperary. Fethard is a quiet spot, only becoming busy during the summer months when the tourists arrive.

I first visited Fethard as an eight-year-old in 1984. My uncle and aunt, over from London, had rented Dungulph Castle, a Norman-era fortified dwelling about a mile and a half outside Fethard, and had invited my parents and me to join them and my cousins for a family holiday. The castle is an impressive building, especially for eight-year-olds with active imaginations. Built by the Whitty family in the fifteenth century, it still has many of its original defensive features, including a tower with arrow slits, a turret and a machicolation from which stones or burning hot pitch could be dropped on the enemy. It has a venerable history, withstanding siege and arson over the years. In 1642, a party of English soldiers from nearby Duncannon Fort attacked rebels who were holed up in the castle. The defenders managed to beat them back. The bodies of sixteen of the soldiers are believed to be buried in the vicinity. The Devereux family, one of the foremost rebel families on the Hook, were tenants during the 1798 Rebellion. The castle was burnt in reprisal. The Cloney family moved in shortly afterwards.

The castle was divided in two in the 1980s. One side was given over to paying guests. Sen and Sheila Cloney lived in the other side. The Cloneys were farmers. Being from Dublin and with little experience of the country, I was fascinated by the farm and thrilled to be allowed help bring the cows in for milking or gather the hay. In this way, I got to know the Cloney family Sen and Sheila, their daughters, Eileen, Mary and Hazel, and their grandchildren. Sen and Sheila were then in their late fifties. Sen was a rather unusual character, not at all the archetype of the Irish farmer. He wore a beret, de rigueur perhaps for his brethren in Provence or the Basque country, but a rare enough sight in rural Ireland. He had a slight stoop owing to a problem with his spine, and piercing blue eyes which gave him an owlish demeanour that went hand in hand with his talent for storytelling and his love of learning. He was a great conversationalist, someone with a natural curiosity about other people. Sheila, on the other hand, was less visible. Whereas Sen was often to be found pottering about the farmyard, eager for a chat, Sheila was more shy and rarely emerged from the other side of the castle.

During that summer and on return visits to Fethard, Sen shared his considerable knowledge of the Hook with our family. He was a keen local historian, particularly interested in the Colclough family, who had lived in the nearby Tintern Abbey from the suppression of the monasteries in the sixteenth century right up until the middle of the twentieth century when the last resident handed the abbey over to the care of the State. Such was his enthusiasm for history that, after the days work, he would retreat to his study on the top floor of the castle and spend hours poring over his research. Often he would work into the early hours of the morning. When correspondents from all over the world would get in touch with him looking for information about some distant forebear who lived on the Hook, he would respond graciously, even though it meant he had less time for his own researches.

One evening, as the sun was going down on a glorious summers day, I was standing in the farmyard with Sen and my father. They were leaning on a gate in the farmyard, chatting. My father mentioned that we had made a pit stop earlier that day at Loftus Hall, the hulking Victorian mansion close to Hook Head. The Marquis of Ely, the principal landowner on the Hook, had built Loftus Hall on the site of a previous building towards the end of the nineteenth century. It was an unpropitious time to embark on such an ambitious project. Building work began in 1870, the year of Gladstones first Land Act. During the next decade, the worsening economic situation on the land, caused by a slump in agricultural prices, led to increased agrarian agitation. The Land War, which was particularly violent on the Hook, eventually ended in defeat for the old ascendancy landlords. In 1913, the Ely estate put Loftus Hall up for sale. It became a Benedictine and, later, a Rosminian convent. In the early 1980s, it was privately owned and was run as a hotel. I had found the place intriguing. As my mother and father had a drink we were the only customers in the deserted bar I had wandered off on my own to explore the long, empty hallways. By the time we arrived back at Dungulph, I was well acquainted with its nooks and crannies.

After chatting with my father about the history of The Hall, as it was known locally, Sen turned to me and asked did I know that it was haunted. I said I did not. With a mischievous grin, he began telling me about a foul, stormy night many years before when a stranger on horseback knocked on the door of Loftus Hall then owned by the Tottenham family looking for shelter. After giving him something to eat and drink, the head of the family, Charles Tottenham, invited his guest to a game of cards. Also present was Tottenhams daughter, Anne, who immediately took a fancy to the handsome young stranger. However, during the game, when Anne dropped one of her cards and bent down to pick it up, she discovered that where the handsome strangers foot should have been, there was instead a cloven hoof. She let out a most dreadful scream. Whereupon the Devil revealed himself and shot through the ceiling, leaving a crack which could never be repaired. Poor Anne went instantly mad and was locked in her room, never to emerge again. She was buried in one of the closets. Sen looked me in the eye. And her ghost still haunts Loftus Hall, he said. A cold shiver ran through me as I recalled my wanderings alone around the deserted mansion earlier that day.

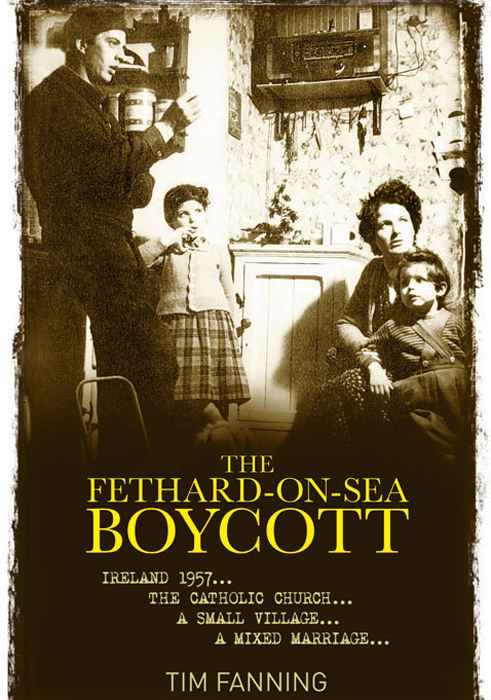

On the last night of our holiday, my uncle invited Sen to join us in the sitting room on our side of the castle for a farewell drink. The room was full, the adults chatting among themselves, the children switching in and out of their conversation. Then, my father, also a historian, asked Sen did he know anything about the infamous boycott which had taken place in Fethard in the 1950s. A grin came across Sens face; he paused and replied, I should. I was the man involved. There was a moments silence. The rest of us non-historians wondered why my father looked so sheepish.

That was the first time I had heard about the boycott. I was only eight years old and didnt think much more of it for many years the story of Loftus Hall had a greater impact on me. My summers in Fethard were taken up with exploring the farm or being taught the rudiments of hurling by Sens grandson David. But bit by bit, over the years, I learnt more about the story and became fascinated. Sen was a Catholic. His wife, Sheila, was a Protestant. They had initially agreed that their children would be raised in both traditions. But Sheila had signed a piece of paper promising to raise the children as Catholics when she got married, as was prescribed by Catholic teaching. Eight years later, when it was time for the Cloneys eldest daughter, Eileen, to begin her schooling, Sheila decided that it was up to herself and Sen to make the decision about which school she would attend. The local Catholic clergy disagreed and told her, in no uncertain terms, that Eileen was to be sent to the Catholic school. Refusing to be told what to do by the priests, Sheila left home with her two daughters, whereupon the Catholics of the village, at the bidding of the two local priests, began a boycott of the Protestant-owned shops and farms in Fethard.