Photo Albert Zawada

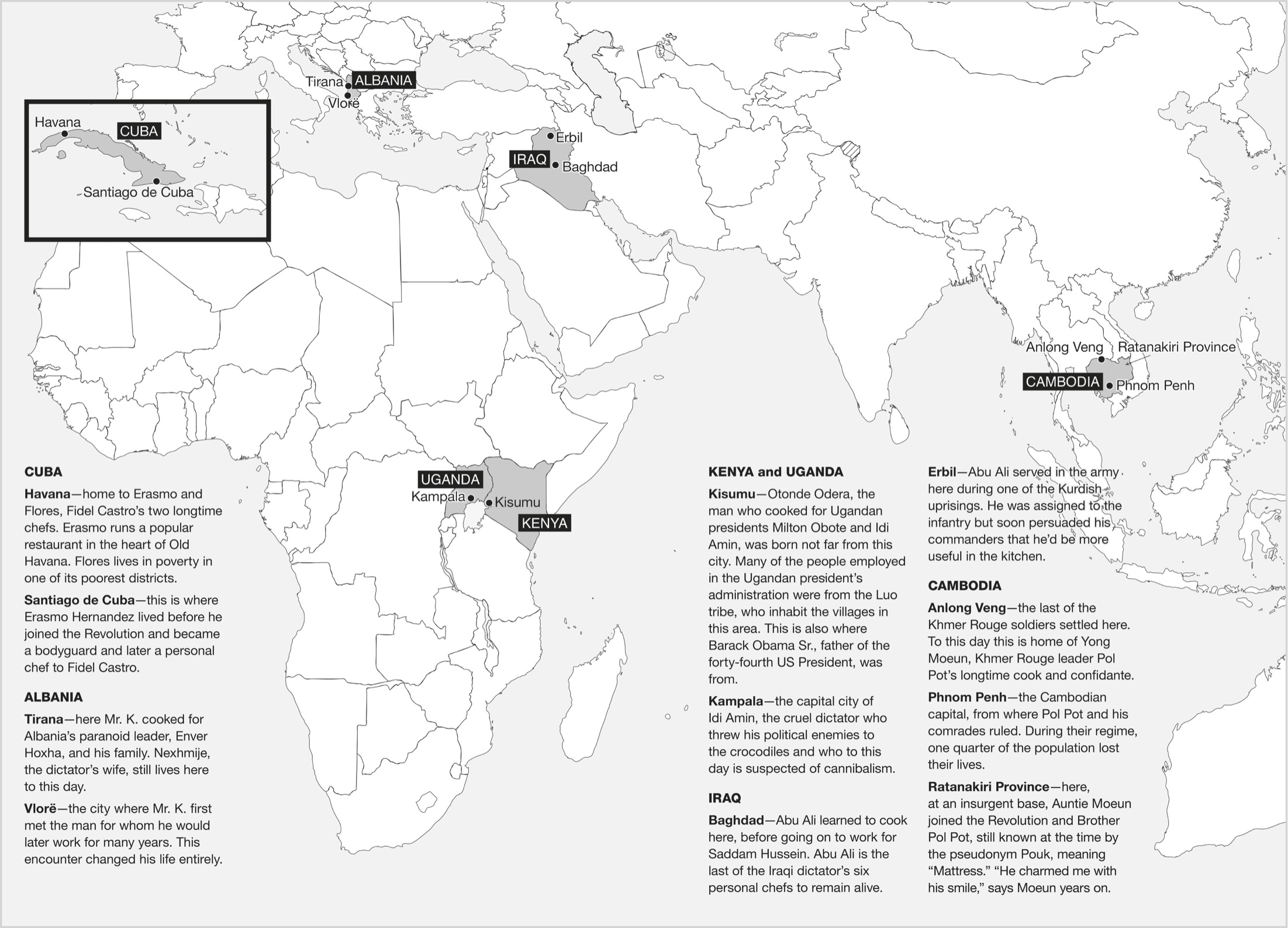

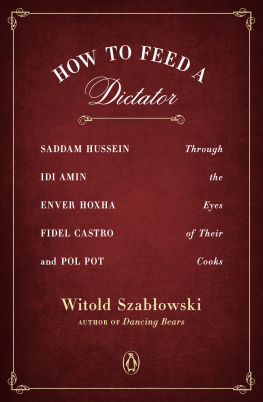

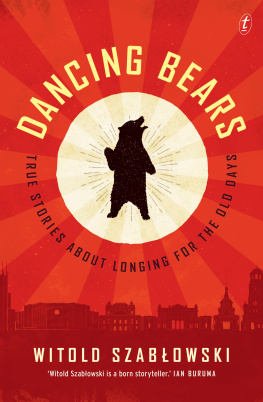

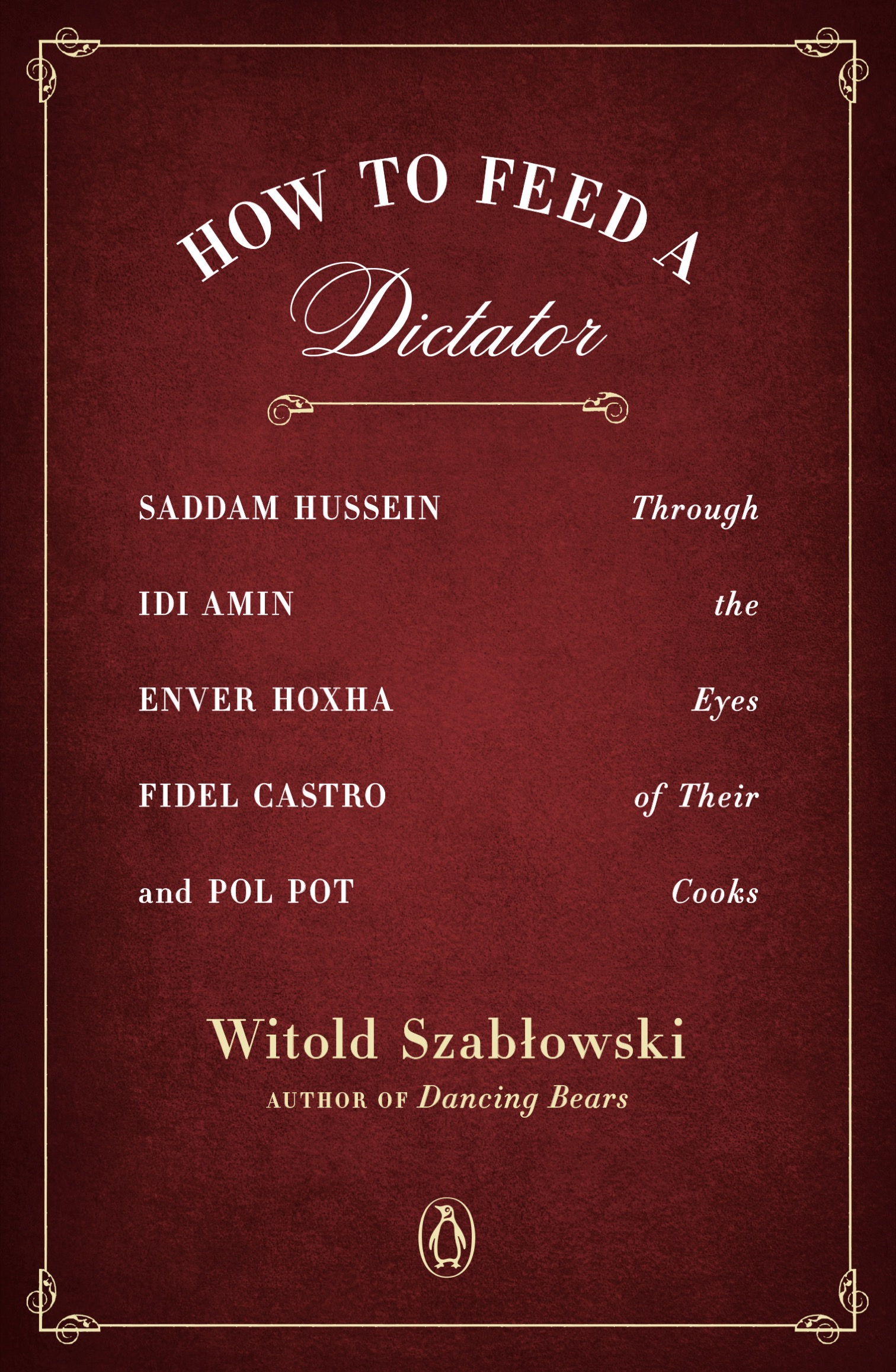

Witold Szabowski is an award-winning Polish journalist and the author of Dancing Bears: True Stories of People Nostalgic for Life Under Tyranny. When he was twenty-four he had a stint as a chef in Copenhagen, and at age twenty-five he became the youngest reporter at one of Polands largest daily newspapers, where he covered international stories in countries including Cuba, South Africa, and Iceland. His features on the problem of illegal immigrants flocking to the EU won the European Parliament Journalism Prize; his reportage on the 1943 massacre of Poles in Ukraine won the Polish Press Agencys Ryszard Kapuciski Award; and his book about Turkey, The Assassin from Apricot City, won the Beata Pawlak Award and an English PEN award, and was nominated for the Nike Award, Polands most prestigious literary prize. Szabowski lives in Warsaw.

Antonia Lloyd-Jones translates modern fiction, reportage, poetry, and childrens books by several of Polands leading authors. In 2019 her translation of Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, was shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize. She is a former co-chair of the UK Translators Association.

PENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2019 by Witold Szabowski

Translation copyright 2020 by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Originally published in Polish as Jak nakarmidyktatora by Grupa Wydawnicza Foksal, Warsaw

This publication has been supported by the POLAND Translation Program.

ISBN 9780143129752 (paperback)

ISBN 9781101993392 (ebook)

Cover design: Alex Camlin

pid_prh_5.5.0_c0_r0

Menu

Menu

If we are what we eat, cooks have not just made our meals, but have also made us. They have shaped our social networks, our technologies, arts and religions. Cooks deserve to have their story told often and well.

Michael Symons, A History of Cooks and Cooking

Starter

Knife and fork in hand? Napkin on your lap?

Ready or not, please be patient for just a while longer. First theres going to be a short introduction.

Before we move on to the main menu, Ill tell you the story of how I almost became a cook myself. In my early twenties, I had just graduated from university when I went to see some friends in Copenhagen. One thing led to another, and a few days later I found a job there washing the dishes at a Mexican restaurant in the city center. It was under the table, of course, but in four days I earned as much as my mom did in an entire month as a teacher in Poland. That helped me to tolerate the burned fat, the smell of which I could never wash out of my clothes or skin, and the crappy decor. At our restaurant you were constantly tripping over a cactus, and on the walls there were fake Colt holsters and sombreros on hooks, which at least one of the tequila-sodden customers would try to steal every single night. The way into the dining area was through saloon doors that were straight out of a Western; the kitchen was the only space with doors that could be closed.

And a good thing, too. Better for the clients not to know what went on in there.

There, over the cooking pots, cigarettes dangling from their lips, stood the chefsall of them from Iraqi Kurdistan. Theyd been drafted in by the owner, an Arab, who cruised about town in a swanky new BMW. Hed bought the place from an aging Canadian whod grown tired of owning a Mexican restaurant in Copenhagen. I dont know how much he paid for it, but business was booming.

There were six chefs in total, and they all had their hands full from dawn to dusk. None of them had ever been to Mexico, and I suspect that if youd handed them a map, theyd have had trouble pointing it out. I dont think any of them had ever been a chef before, either. But they were taught how to make burritos and fajitas, how to fry chicken Mexican-style, and how to add a small squirt of sauce to the tacos in a way that made it look as if theyd added lots. So they worked away, frying and squirting. The customers loved the food, and that was all that mattered. Theres no work in Iraq, the chefs would tell me, as if they had to explain themselves.

They taught me to smoke marijuana before starting work. Otherwise its unbearable, theyd say as they blew out smoke. They taught me to count to ten in Kurdish. They also taught me a few swear words, including the rudest one, which had something to do with your mother.

I spent the entire day working three dishwashing machines and scraping burned chicken out of the large pots by hand. In the rare spare moment, I tried to tame a rat that lived on the garbage heap by offering him scraps; I got this dumb idea from a movie. Luckily, the rat was smarter than I was and wisely kept his distance.

The Kurds were great co-workers; they planned my future career for me. Well teach you to cook, they promised. You wont have to wash dishes all your life.

Thats what I, too, was hoping. So I learned to make burritos, fry chicken, and squirt sauce on the tacos exactly as they did.

Until one day my cell phone rang. Someone had told the owner of another restaurant about the guy who was willing to work off the books. The other owner wanted to make me a better offer. This time Id get as much as my teacher mom in Poland earned in a month in three days instead of four. Plus Id be promoted to assistant cook. Without a second thought I said adios to the Kurds. Two days later I was putting on a black apron and taking up my post by the gas stove in a small but popular restaurant just off Nrrebrogade, one of the citys main arteries. This time there were two of us manning the kitchen: the owner, whose name was August, and me, Witold, his assistant.

August was half-Cuban and half-Polish, but hed been raised in Chicago and didnt know a word of either Spanish or Polish. Hed spent most of his life working as a cook on cargo ships. The restaurant was meant to provide his pension.

Until the clients appeared, you could talk to August quite normally, but as soon as the lunch hour cameand out of our eight tables, lets say six were occupiedthe devil got into him. The pans would rattle, the plates would fly, and August would scream. Hed hurl vulgar abuse at all his staff, with his wife bearing the brunt of it; she ran the bar and was also his business partner.

Menu

Menu